Sophie Baggott reviews Gen, a collection of uniquely Welsh poems from People’s Choice Award and Wales Book of the Year winner, Jonathan Edwards.

“So here they come, around the corner, | bouncing, flouncing, boho | beehives…” begins Jonathan Edwards’ titular poem in the first quarter of his collection Gen.

Among an otherwise nimble series of poems, it is odd that the namesake piece and the final one are uncharacteristically tedious. While ‘Gen’ catalogues clichéd images of the young – piercings, tattoos, shaven heads, digital devices, ‘Song’ clamours for an individual (addressed only as “girl”) to come to the poet by listing the ways she could reach him: “So come to me, by plane, by train, by car, | by unicycle, girl, by self-drive van…”. Both seem a little tired, and tiring; the recurring demands to “girl” in the latter wore me down somewhat.

Happily, though, these poems bookend a thoroughly engaging bunch. Roughly divided into four themes – youth, character sketches, Wales, and lust – the pages hop nonstop between unalike centuries and voices. Some things remain steadfast: the tone never has airs or graces, with talk of “bumfluff” and “dude”, “being pissed” and “piggyback”; two fingers are always stuck up to authority; emotions are generally haywire. Sometimes the temper rises, “bloody” this or “bloody” that. It’s pretty fun.

Clues as to the bigger picture may be in the words that recur: “retro”, “empty”, “flouncing”… The collection is at times a frenetic rush of messy emotions and desires, at times a crumbly monument of inevitable decay. Across the opening chapter on youth (the longest of the four), the nostalgia is outweighed in my view by a sense that all good things come to an end. In ‘My Father Buying Sweets, 1956’, the boy is not even permitted the joy of sugar without foreboding: “There are years | in which the shop will go to bedsits, the bedsits | to ruin, my father’s mouth will bloom | with fillings”. Life is exhilarating, nonetheless, and simple – at one point we see the poets’ parents getting arrested for their “salt-of-the-earth” characters.

Edwards finds reasons to empathise with all manner of objects and animals; anthropomorphism is his speciality. He manages to humanise a crocodile, a Welsh flag, even a retail park tree. One of my favourite poems is ‘Newport Talking’, in which we hear a typical day in the life of Newport. Opening with “Me? I get up early, see”, the city goes on to guide us through its sunrise, traffic, idle horses (“chewing is hypnosis”), shoppers, and partygoers. It pauses on a handful of residents: the old lady who misplaces her umbrella, for instance, and the homeless man who sleeps outside Debenhams. This one holds Newport’s attention. The city has watched the man stare down into the water from the bridges he has relentlessly re-crossed, and now tenderly hovers close to the sleeping man to check his breath “here in this doorway, | here in the place exactly where my heart is.”

Edwards’ interest in overlooked locals feeds into some of this collection’s most moving moments. ‘The Landlord at The Philanthropic’ is a kaleidoscope-poem of alternative ways to look at a man behind a bar. From one perspective “he drives the world”, pulling pints as if shifting gears; another perspective merely reveals his bald patch. The man remembers all the punters’ birthdays, and drinks a glass of milk after each shift. Edwards renders him a figure worthy of curiosity and admiration, just as he does on a greater level with Wales itself.

The poems about Newport and the landlord fall in the third chapter, and are Edwards’ very strongest, focused on our country’s past and present. He reaches further back than his parents’ and his youth now, stretching right back to “the first Welshman” – alternatively known as the Red Lady of Paviland – who was discovered (and misgendered) on the Gower Peninsula by an Oxford professor in 1823. The patriotic pride here seems to be laced with a muted anger that the Welshman is slandered and steered by Englishmen.

This is followed up with patriotic fury, explicit this time, in a sequence on the drowning of Capel Celyn and the Aberfan disaster. ‘Cofiwch Dryweryn’ is a direct call – echoing the famous graffiti in Ceredigion – to remember the flooding of the Tryweryn valley that sank an entire village, Capel Celyn, to construct a reservoir for a Liverpudlian waterworks. As the village was a stronghold of Welsh language and culture, its erasure was deeply controversial. Edwards writes of it beautifully, particularly in these lines:

Breaking the surface, the tip of the spire

of the waterlogged church

is a radio aerial bringing the news

of another century to those submerged.

Again we see the grief over what is now lost – an ache that runs throughout the collection – which imbues Gen with hiraeth: an intrinsically Welsh feeling of longing, though in most cases we can’t quite articulate what for. Here Edwards mourns a village, but it’s more than that:

Could you give the past

a piggyback to the surface, then stand on the bank

and open the letter to find those pages

blank, blank

The fourth poem, ‘Aberfan’, is a fly-on-the-wall to the final morning at a school in Glamorgan before a colliery spoil tip collapsed, killing 109 pupils and five teachers. Other locals also died at the scene. The poem is light-hearted (“this spring-limbed, bobtail bunch, these yay-high | heroes, ragamuffins”) in Edwards’ typical style, but as they settle in their chairs after assembly “the world breathes in”. He pauses the poem ahead of the disaster, leaving us with a devastating stillness.

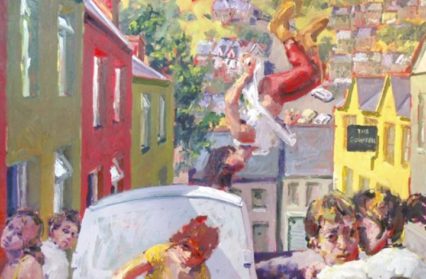

After this searing section I found the last chapter on relationships anti-climactic, and was turned off by Edwards’ use of “girl” in the second person: “So right now girl I guess you find it hard … There is a reason girl I know all this”. The chapter’s first poem is even titled ‘Girl’. Another is called ‘The Girl in the Coffee Shop’ and begins with “is a girl”. It rang an antiquated bell and felt slightly vacuous after the previous chapter’s potency. Yet my disappointment in this last chapter does not negate what is, on the whole, a stimulating collection. The cover image by Welsh painter Kevin Sinnott sums Gen up well: tumultuous, colourful and distinctly of its age.

Gen by Jonathan Edwards is available now from Seren.

Sophie Baggott is a regular contributor to Wales Arts Review.