Thomas Tyrrell reviews Saints and Lodgers, a new selection of the poems of ‘self-proclaimed super-tramp’ W.H. Davies.

Across the twentieth century, no figure lost as much standing in the public imagination as the tramp. You can still, albeit with difficulty, call him to mind: his roguish smile, his dirty face, his gnarled hands ready to turn to any honest or dishonest task. On one side, his descendants are the outlaws lurking in the greenwood; on the other, the distressed young gentlemen of Dickens’s novels. Chaplin made him a worldwide icon of the silver screen. Just William wanted to be him when he grew up. Yet as the century aged, he lost his strength and individuality. No longer roaming where he would, he was found every day at the same old street corner. New addictions and bureaucracies arose to chain him in place, and he became one among a multitude defined solely by what they lack: the homeless. And we’re the poorer for it.

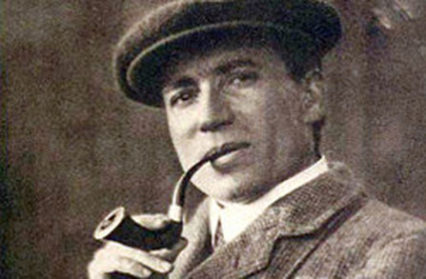

W.H. Davies, the self-proclaimed super-tramp, is one of the best chroniclers of that brief hey-day. His Autobiography of a Super-Tramp takes us through a life spent roving between Britain and North America, riding over with the cattle ships, supplementing casual labour with beggary and jumping boxcars to get around. One day, he jumped a little too late and lost a leg. Undeterred, he returned to London and began selling his poems door-to-door. Miraculously, discovery followed. His memoirs were published to great acclaim, and his poems sold so well he was able to retire into the country with his wife, a former prostitute. (He had tried to publish a memoir of their romance, but it was so scandalous it had to be printed posthumously).

It seems very odd that such a man should need rescuing from his own respectability. Yet the collected poems of W.H. Davies sat stolidly beside the poems of Rupert Brooke and John Milton on my grandparent’s bookshelf, and not once did that sober, respectable volume ever come home rascally drunk, steal a chicken, or run away to Canada to jump boxcars. Glancing into it, I found it to be full of idealistic nature poetry, strongly influenced by William Wordsworth. His most famous poem, ‘Leisure’, is so well-mannered that it found its way into a series of Center Parcs adverts. So this new selection, Saints and Lodgers, should be heartily welcomed for restoring to the verse some of the racy roguishness on the prose memoirs.

As Jonathan Edwards acknowledges in his lively introduction, Davies’ poems have their limitations. They would be better poems in general if ‘thou’ and ‘thy’ were replaced by ‘you’ and ‘your’; something that lies outside the remit of even the most buccaneering editor, but which I heartily recommend to the readers, who may do what they like. It instantly reduces the mighty shadow that Wordsworth throws over the poems and makes them speak out with a stronger and more authentic voice. Selection also radically improves them, and Edwards has done a marvellous job finding out the poems that speak directly to Davies’ life and his experiences, rather than what he engagingly calls ‘Another Bloody Poem About Birds’.

A surprise for the modern reader is how little time W.H. Davies spends lamenting his own condition. Beggary does not bother him so long as he is in motion, outdoors with a glimpse of nature. If he thinks the tramp’s life is wretched, he thinks the life of the wage slave is just as bad. There are vivid vignettes of life amongst the lodging-house folk and urban poor Davies lived alongside, but the most political of all these poems is a lament against a tax on ale. For him, a glimpse of nature is the sovereign remedy for all ills of the spirit, a message that comes to us more strongly now that 100 days of lockdown have given us our own time to stand and stare, and made us value all the more the natural spaces that are left to us.

One of the appeals of these poems, as Edwards writes, is that they can speak to people growing up in Wales not knowing that their environment ‘has been written about in that way, or that they can be written about.’ I will not take the Bristol train again without looking for ‘Twm Barlum, that green pap in Gwent, | With its dark nipple in a cloud’, or pass by a cornfield without thinking of the wind ‘Dragging the corn by her golden hair | Into a dark and lonely wood.’ And we’re the richer for it.

Saints and Lodgers by W.H. Davies will be released in September 2020 and is available to pre-order at Parthian Books.

Thomas Tyrrell is a regular contributor to Wales Arts Review.