Award-winning novelist Hayley Long remembers her close connections to the continent from her childhood postcard correspondences.

The other day, my mum handed me a carrier bag. ‘I’ve had a sort-out,’ she said. ‘And these are yours if you want them.’

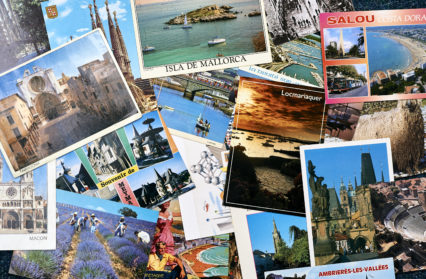

Peering in at the contents, I saw lots and lots of postcards.

‘You sent them to me,’ said my mum. ‘And now you can have them back.’

What followed next were two weird hours spent in the company of my younger self. From September 1989 until April 1996, I left a paper trail of my life on postcards to my mum. At the start of this time, I was 18 years old and had just left my hometown of Felixstowe to study English at Aberystwyth University. In spite of the many funny memories I have of student life, the messages I sent home were so humdrum that they raise a smile only by accident. On one card, I wrote, Last week everyone complained about the hall food + it has got ever so slightly more nicer [sic]. The other day, I had workmen in my room fitting a smoke detector because our hall didn’t comply with safety standards. These thrilling insights set the tone for the entire collection. No wonder my mum was giving the postcards back.

My regular reports home continued throughout the whole of my degree and covered a summer spent in North America before going on to document a stint working for a tour operator in Tunisia. But the vast majority of the cards coincided with an eclectic spread of temporary jobs in various countries in Europe. The final postcard – by this point I am approaching 25 and have some English teaching experience under my belt – is a nail-biting cliff-hanger sent from Prague in April 1996. I’m fine, I tell my mum. I’ve met some more English teachers looking for work and we’ve all stuck together. Prague is absolutely beautiful and beer is 20p a bottle! I’ll try the Berlitz School on Monday, I think. Hopefully they’ll give me a job. Speak to you soon.

As it happened, Berlitz did not give me a job and soon afterwards I hopped on a Eurolines bus to Strasbourg to try my luck there instead. Evidently that drew a blank too because shortly after, I returned to the UK, enrolled on a PGCE course and spent the next seventeen years furiously spinning plates in state education. My postcard days had come to an end.

Reading through my scribbled messages more than twenty years later, I can’t help but be struck by what an extraordinarily exciting time I’d had. Not that this is reflected in my observations. My boss is a shambles, I tell my mum on a card from Barcelona, but there’s a Marks and Spencer’s here. From northern France, I wail, There’s this guy I fancy but he’s 6ft 4 – why couldn’t he be a bit shorter? And another time, in southern France, I write, Today I was (briefly) in Orange. My job is still a pain in the backside. My postcards could almost be lyrics to songs by The Smiths.

What is apparent is the carefree nature with which I moved across Europe. In the early nineties, I blithely roamed from country to country seemingly oblivious to how lucky I was. I make no mention of work visas or obtaining firm job offers before travelling, or of that thing we now hear so much about called The Free Movement of People. The free movement just happened and I took it entirely for granted and assumed it was my natural entitlement. Sometimes, as with Prague and Strasbourg, I rocked up in a new place with very little money and even less of a plan. On a postcard stamped in Brussels but depicting Bruges, I cheerfully wrote, Tracey seems quite happy to let me stay here for the time being. I’ll check out my chances and see if I can find a teaching job + just see what happens. In fact, I stayed for a year or so. The world – or Europe anyway – was my oyster.

Or most of it was. I was aware that some parts were a no-go. But while war raged through the former Yugoslavia and closed those doors, a powerful wave of optimism was unlocking others. The Iron Curtain had recently fallen and Europe in the early nineties seemed bigger and more exciting to me than it ever had before. If I’d been a bit more clued-up, I might have recalled the strange words that had dominated the news in my teens – words like perestroika and glasnost and Solidarity – and identified the direct impact that they were now having upon my life. Eastern Europe – closed throughout my entire childhood – was increasingly open for business.

And the Europe I did know was changing too. Had I followed the news at all, I would surely have been aware of the Maastricht Treaty which was signed while I was in the final year of my degree. Thanks to this treaty, I graduated just as the UK agreed – along with twelve other states – to respect four fundamental freedoms: the free movement of goods, services, money and, crucially for me, people.

If I’d had an inkling of any of this, I like to think I would have danced on the spot and thanked my lucky stars that I was young and alive at a time when my own country’s government and many other governments in Europe were making bold moves towards greater openness and unity. Instead I just bought my bus tickets and dragged my backpack around Europe without a second thought.

The prospect of a more isolated Britain makes me deeply uneasy. Recently, I met up with British friends I’d made while living abroad. It quickly became apparent that they were uneasy too. One of them had applied for an Irish passport because he had an Irish grandparent. Another, with family links to Italy, was thinking of applying for Italian citizenship. At a time when so many people face an uncertain future in the UK, it pains me to admit that I felt a selfish twinge of regret because my family tree is so inflexibly British. ‘Hey, but at least my one and only passport will be blue,’ I quipped, ‘and won’t that be nice to look at when I’m waiting in a long queue?’

Of course, Britain’s departure from the EU doesn’t necessarily mean that living, working and travelling in Europe is about to get more difficult. After all, the Czech Republic didn’t join the EU until 2004 and yet – as my postcards testify – I was knocking on the door of the Berlitz School in Prague as long ago as 1996. But back then, the political climate all seemed so much sunnier. Back then, I never heard a single person talk about ‘defending our borders’ and it would have seemed inconceivable to me that anyone might ever say such a thing in peacetime. Back then, I was a freewheeling Brit abroad – an economic migrant, if you like – and if any of my European friends hadever made any remark which suggested I wasn’t welcome, it’s no wonder that I never heard them. I was too busy laughing with my new mates and speaking French very badly and working and moaning and sending postcards from Spain or Belgium or wherever it was that I happened to be. Those postcards are memories of living in another Europe. For the sake of future generations, I really hope that the freedom I once enjoyed so enthusiastically doesn’t become a memory too.

Hayley Long has done a fair amount of freewheeling around Wales too but now writes fiction for teenagers. Her most recent novel, The Nearest Faraway Place is shortlisted for the 2018 Tir Na n-Og Awards.

(Image credit: Andi Sapey)