Black Mountain Jazz’s annual Wall2Wall Festival in Abergavenny this month will devote one evening to celebrating 100 years of jazz on record and the centenaries of Ella Fitzgerald, Dizzy Gillespie, and Thelonious Monk. Nigel Jarrett looks ahead to the action.

Revolutionaries are scarcely aware of the circularity implied in the word ‘revolution’; the idea that what goes around comes around. Because the wheel has stopped turning or is moving too slowly, they want to set it in motion again and travel faster, if necessary destroying everything in their path. In politics, the revolving motion is intended to arrive at the start in better, more improved shape; in art, it’s a twist of the kaleidoscope, each turn resulting in a different pattern, not necessarily better than its predecessors. Without a moral evaluation, art thus trumps politics in being primarily ever-expanding rather than ever-changing. Change in politics is often for the worse, and with casualties innumerable. With art it’s different, and sometimes a new wheel is constructed.

In 1917, a group of white musicians called the Original Dixieland Jazz Band made a recording of Livery Stable Blues. It was the first time jazz, or ‘jass’ as it was known, had been captured for posterity. It was crude and it was polyphonic, a new music, a first revolution of the new wheel, hitherto set in tentative motion by disparate elements, including the European classical tradition as practised by both whites and well-to-do blacks; the calls and responses of black workers in the countryside of the Deep South; religious observances of New Orleans (pagan and Christian gospel); and the entertainments of ‘Negro’ minstrelsy. Add to those the availability of sometimes battered musical instruments left over from military bands in the American Civil War, and new sounds were created, a music capable of making the wheel turn apace. It was to develop as fast and more or less in parallel with recording itself.

Edison had by 1877 devised a way of recording sound on tinfoil-coated cylinders. While he then pursued other interests, Chichester Bell and Charles Tainter developed wax cylinders, which Edison himself further refined ten years later. This coincidence of a new technology with a new music was unprecedented. It wasn’t equivalent to the invention or improvement of musical instruments in Western classical music, even though these often gave composers and practitioners new opportunities. Composition in jazz was and is, theoretically, on the hoof and on the spot, even though a framework may be written down or formulated as a basis for extemporisation. Thus, the duration of Livery Stable Blues as a recorded piece was limited to how long it took for a cylinder or disc to revolve. When played ‘live’, it could be as long as it took. To put it broadly, classical music has no place for improvisation, unless one includes a concerto cadenza (itself often written by divers hands when not by the soloist) and contemporary ‘classical’, which might borrow jazz’s unpredictability for new ends. There are no extended solos in Livery Stable Blues. There wasn’t time for them. It was collective ensemble playing, with novelty ‘breaks’. Notated classical music on record, in contrast, was as long as the notation lasted, so that Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony on 78rpm shellac of the sort made for universal sale might consist of several discs.

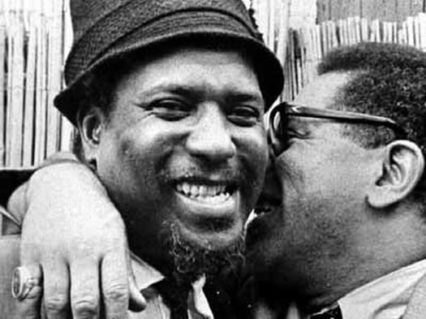

Both radio broadcasts and the advent of the LP record enabled jazz to move away from the restricted time frame of early recordings. It did not allow jazz to ‘stretch out’ but it enabled non-recorded stretching out to be accommodated and enshrined. In jazz the performer is paramount, and jazz records have immortalised those parts of the music’s history in which individuals have enlarged the firmament. Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Ornette Coleman are among them. So-called ‘classic’ jazz discs, unlike many counterparts in other forms of music, almost always represent stylistic departures, as in Davis’s Kind Of Blue, Coltrane’s Giant Steps, Coleman’s confidently prescient The Shape Of Jazz To Come, and, further back, Benny Goodman’s Carnegie Hall Jazz Concert, and Jelly Roll Morton’s Mr Jelly Lord. (Davis, not incidentally, made significant departures throughout his career; almost every new LP of his was a revelation as well as a revolution.) Trumpeter Gillespie, who with Parker discovered that skimming the top notes of a formal chord sequence provided the basis of a new way of playing a tune, thus helping to invent Be-bop, was born in the year the ODJB made that first record. So was Ella Fitzgerald, the epitome of the jazz singer whose voice constantly aspires to the condition of a musical instrument and almost becomes one itself; and Thelonious Monk, whose catchy tunes and spikily angular style of playing the piano turned keyboard dynamics inside out. The CD and streaming have further enhanced jazz listening by consolidating the music’s history through re-issue. Recordings of classical music does the same to a lesser extent, but commercially its main interest lies in promoting new, non-improvising musicians with different takes on established notated works. In jazz, new musicians are the new composers, whether they perform tunes written by others or by themselves. As in all surveys of history, of course, prosaic matters often count for much. Also in 1917, the US military insisted that the New Orleans ‘red light’ district of Storyville, despite its being a place where prostitution could be regulated and monitored, should be closed to preserve the health of fighting men, among whom transmitted diseases were spreading like a dose of the clap; in fact, it was a dose of the clap. Jazz musicians who relied on the place for work moved elsewhere, looking for new opportunities and spreading their musical influence. So spun the wheel even further. And faster: less than thirty years after Livery Stable Blues, jazz as played by the ODJB was a thing of the remote past. But, thanks to recording, a past that has been preserved.

The four-day Wall2Wall Festival begins on Thursday August 31. The variety of jazz spawned by what happened 100 years ago will be illustrated at its celebration on September 1, with a specially-created stellar band of musicians, to be live-streamed with other selected events. For full details of the four-day festival at the Melville Centre and other venues in Abergavenny, go to its website: http://blackmountainjazz.co.uk/wall2wall-jazz-festival/

Nigel Jarrett writes regularly for Wales Arts Review and for Jazz Journal magazine. He’s a winner of the Rhys Davies Prize for short fiction and has published a novel, Slowly Burning (GG Books), two collections of stories, Funderland (Parthian) and Who Killed Emil Kreisler? (Cultured Llama), and a collection of poetry, Miners At The Quarry Pool (Parthian).

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.