Drawing on a personal dataset of 3,000 book inscriptions, and in partnership with Cardiff University’s Special Collections and Archives, linguistic ethnohistorian Dr Lauren Alex O’Hagan aims to rethink the life of the Edwardian working classes in a new Instagram project and physical exhibition.

The British working classes are often given a raw deal. Widely accused of having nothing interesting to say, their voices tend to be ignored, silenced, demonised, stereotyped or sanitised. The Grenfell Tower disaster and the suicide of a participant on The Jeremy Kyle Show are just two recent examples of this tendency. Furthermore, when the working classes do speak up, such as by voting leave in the 2016 EU referendum, they are quickly ridiculed and branded as “uneducated” or “ignorant.”

For some years now, starting with the work of E.P. Thompson in the 1960s, and more recently with Tim Hitchcock’s ‘New’ History from Below (2004), there have been growing calls to recognise the voices of the unrepresented and give them power over their own history, life and culture. The working classes have a rich cultural identity that is worthy of being acknowledged and celebrated. To ignore it is to ignore a piece of ourselves. To paraphrase The Guardian columnist Owen Jones, it’s now time to paint the working classes back onto the historical canvas. And that is exactly what my current project aims to do.

Contrary to clichéd assumptions about their lack of education, the Edwardian working classes were highly literate. By the beginning of the Edwardian era (1901-1914), just five per cent of the British population was unable to read or write. This mass literacy was the result of more than twenty years of free and compulsory education. Rapid changes in book production methods also meant that the prices of books had decreased dramatically, making their purchase possible by the working classes for the first time. Access to literature sparked an awareness of the inequalities in British society and brought about a new sense of community spirit amongst the working classes – who represented 75% of the population – centred around collective pressure and mass protest.

The working classes began to question the older division between “those who served and those who were served” and became active participants in the labour movement, which led to the widespread development of trade unions and the formation of the Labour Representation Committee (which became the Labour Party in 1906). They formed mutual improvement societies, accessed Mechanics’ Institutes and Miners’ Libraries and attended Workers’ Educational Association classes to exchange ideas and share experiences. This wave of industrial militancy and political mobilisation meant that no longer were the working classes, helpless bystanders, with no say in the decisions made by Westminster.

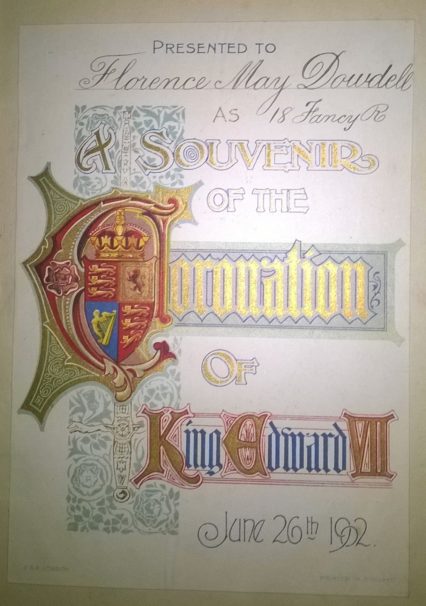

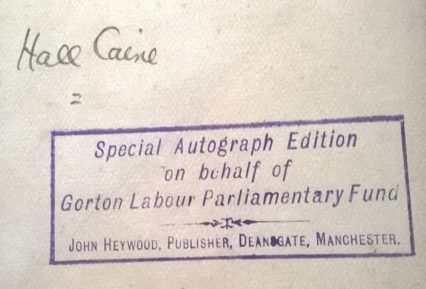

One surprising way in which many of these working-class changes are captured is in the Edwardian book inscription. These traces of ownership left behind in books provide unprecedented knowledge of working-class life and culture in early twentieth-century Britain, standing as important first-hand evidence of people’s identities, social circles, jobs, hobbies, beliefs, hopes and fears. Choices of language, image, typography, colour and texture were all used to explore options of identity and a sense of belonging to a wider world, as well as to make statements, whether on a personal or political level.

Individuals could be highly creative, playing around with layout and composition, as in the servant Ada Mary Harper’s beautiful ownership inscription below which challenges persisting stereotypes on working-class handwriting and respectability. Others used books to record opinions that mattered to them, as in trade unionist Alec Spoor’s declaration that Charles Darwin is “My God” in his copy of The Origin of Species. While some provide the formative voices of future Labour MPs, most capture the voices of those who passed their lives under the radar but made important contributions to Edwardian society in their own ways, whether through serving, sewing, mining, building or teaching.

Through these inscriptions, we can recover the voices of working-class individuals and give them agency as autonomous writers. In doing so, we are able to develop new narratives and fresh understandings of working-class life and culture, challenging harmful myths perpetuated by those in higher positions of power. By bringing personal experiences to the forefront, we can re-evaluate how Edwardians navigated the emerging institutions of the modern state and how their behaviours helped shape these institutions. These inscriptions have the power to demonstrate that the working classes were not easily brainwashed or manipulated and, in fact, we’re able to use literacy to take control of their own lives and improve their own circumstances. In short, they encourage us to look at the working classes in a new light. Without this knowledge of the past, it can be very difficult to challenge the class divisions that still exist in British society. Class is not an unchangeable part of the social order; it arises from conflicts between different groups who are defined primarily by their economic status. Understanding this complex history through the book inscription may give us clues to alternative ways in which the world might be organised in the interests of the many, not the few.

This is the context for the new online project that I am launching on Instagram, as well as a physical exhibition at Cardiff University’s Special Collections and Archives. Prize Books and Politics launches on Instagram on 5th March 2020 (World Book Day) and runs until 1st May 2020 (International Worker’s Day). Drawing on previous digital exhibitions like Dr Alix Beeston’s Object Women, it will feature an image of one inscription per day over 58 days that encapsulates the life of the working classes in Edwardian Britain. Each image will be accompanied by a short written reflection exploring its main message, which aims to encourage readers to rethink current perceptions of the working classes. On 2nd May 2020, the physical exhibition of Prize Books and Politics launches at Cardiff University’s Special Collections and Archives. Throughout the launch day, there will be a range of interactive workshops to try out, including ‘Design Your Own Bookplate’ and ‘Explore the 1911 Census’.

You can follow Prize Books and Politics on Twitter @prizebooksandpolitics or @laurenohagan91 or on Instagram at https://www.instagram.com/prizebooksandpolitics/

Dr Lauren Alex O’Hagan is a Research Associate in the Centre for Language and Communication at Cardiff University. Her first edited volume, Rebellious Writing: Marginalised Edwardians and the Contestation of Power, is available now from Peter Lang.

For other similar content to this article, click here.