2022 marks ten years since the launch of Wales Arts Review, and as part of our celebrations, throughout this year we’ll be revisiting some of the best and most loved features, interviews, and reviews from our archive of nearly five thousand published pieces. Today, we revisit our celebrations of the Roald Dahl centenary, in partnership with Cardiff University, when Ben Screech explored Roald Dahl’s extensive use of the ‘cautionary tale’ throughout his career.

First of all, what is a ‘cautionary tale’?

Cautionary tales are short poems or stories with a moralising function, designed to warn their young audience of the consequences of transgressing rules, often associated with personal safety. They are typically divided into three parts, although they may also, as is the case in Dahl’s work, diverge from this structure considerably. Initially, in a traditional cautionary tale, an act, location, or thing is said to be dangerous. Then, the narrative presents itself. This typically consists of a warning being disregarded, and the child engaging in the forbidden act. Finally, the transgressor comes to, or narrowly avoids, an unpleasant end – typically relayed in heavy-handed detail to re-enforce the original message of why the warning should have been heeded in the first place. Cautionary tales were particularly prominent in the nineteenth-century when children were faced with the puritanical admonitions of writers such as Ann and Jane Taylor, who in Original Poems for Infant Minds caution their young readers against all manner of transgressions ranging from stealing eggs from bird’s nests (the unfortunate thieves are, in turn, plucked from their beds at night by ‘a monster – a dozen yards high’), to remembering to give regular ‘thanks to God’ for their existence, because death is waiting, ready to ‘snatch them away’ at any minute.

Perhaps the most (in)famous collection of cautionary tales was written by the German psychiatrist and author Dr Heinrich Hoffman in 1845. Struwwelpeter contains a broad ranging array of cautionary warnings including why thumb-sucking is inadvisable (a ‘great tall tailor’ will chop them off with scissors), to why one should never leave home in a storm (the wind will blow you away!). Cautionary tales were such a routine presence in Victorian children’s literature that even Alice in Wonderland – (the novel itself, containing many echoes of the genre), we are told: ‘had read several nice little histories about children who had got burnt, and eaten up by wild beasts and other unpleasant things, all because they would not remember the simple rules’.

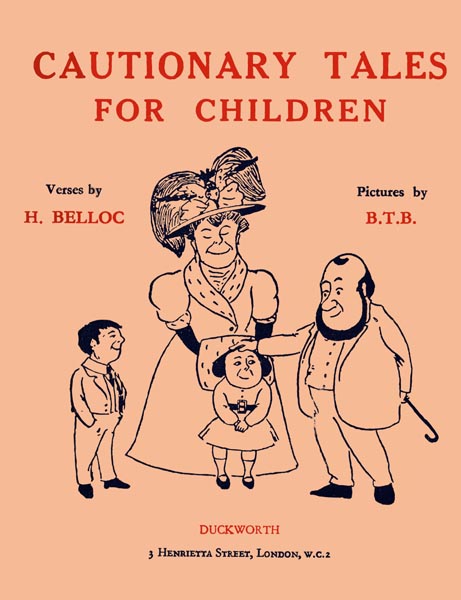

Then, in 1907 comes Hilaire Belloc’s satire of the previous century’s solemn approach to the genre. His Cautionary Tales for Children: Designed for the Admonition of Children between the ages of eight and fourteen years contain the same sense of absurd and grotesque humour we later see playing out in the pages of Roald Dahl. Notably too, the verse from Belloc’s collection entitled Matilda: Who Told Lies, And Was Burned to Death was the initial inspiration for Dahl’s Matilda, who was originally going to be as much of a horror as her namesake. Roald Dahl’s writing, with what Matthew O. Grenby terms its ‘vestigial didactic impulse’ and the ‘salutary violence’ contained within its pages, contains pervasive echoes of these writers’ cautionary tales. Indeed, as Alston argues, Dahl’s fiction speaks to the twentieth-century world of the independent child, and simultaneously looks back to the cautionary tales of the nineteenth century’.

Then, in 1907 comes Hilaire Belloc’s satire of the previous century’s solemn approach to the genre. His Cautionary Tales for Children: Designed for the Admonition of Children between the ages of eight and fourteen years contain the same sense of absurd and grotesque humour we later see playing out in the pages of Roald Dahl. Notably too, the verse from Belloc’s collection entitled Matilda: Who Told Lies, And Was Burned to Death was the initial inspiration for Dahl’s Matilda, who was originally going to be as much of a horror as her namesake. Roald Dahl’s writing, with what Matthew O. Grenby terms its ‘vestigial didactic impulse’ and the ‘salutary violence’ contained within its pages, contains pervasive echoes of these writers’ cautionary tales. Indeed, as Alston argues, Dahl’s fiction speaks to the twentieth-century world of the independent child, and simultaneously looks back to the cautionary tales of the nineteenth century’.

In The Enormous Crocodile, Dahl’s first picture book, the eponymous crocodile plans a series of tricks, and adopts various disguises to dupe the children he hopes will soon become his ‘dinner’. In the manner typical of a cautionary tale, Dahl introduces various characters to warn the children of their eventual fate, should they approach the crocodile disguised as a tree, seesaw, bench or merry-go-round ride. ‘Don’t Ride On That Crocodile!’ the Roly-Poly bird warns the children and, ‘run’ Muggle-Wump the monkey instructs: ‘that’s not a see saw, it’s the enormous crocodile and he wants to eat you up!’ The children escape, (just) and the crocodile gets his comeuppance; being flung into the sun on the final page. For Fats Suela, the didactic / cautionary component of this text is that: ‘it teaches children that it’s best to be on your guard […] That not everyone can be trusted. And that things are not always as they seem’. A comparison might be made with the unfortunate Jim in Hilaire Belloc’s Cautionary Tales who does not have such a lucky escape upon falling victim to a similarly gluttonous lion who, we are told: ‘hungrily began to eat the boy, beginning at his feet’. Children’s literature consistently alludes to a threatening sense of Otherness that exists just beyond childhood’s horizon, and the cautionary tale is no different. Children are vulnerable to the dangers of an adult world, which, like Dahl’s crocodile may not always be as it initially appears. Indeed, this is a theme to which Dahl continually returned throughout his career as a children’s author.

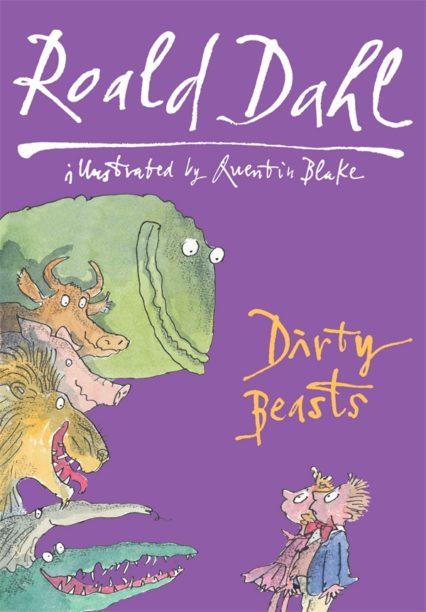

In Dahl’s 1983 poetry collection Dirty Beasts, each poem comprises what is essentially a mini-cautionary verse in which the omniscient speaker warns children why they should beware of the various ‘dirty beasts’ that exist around the world. ‘I would never recommend, that you should treat him as a friend’, the reader is warned in relation to the ‘scorpion’ who’s more than likely to ‘make a sudden jump and sting you hard upon your rump’. In some of the poems, the child whose fallen foul of the animal in question relates their experience directly to the reader, imploring them not to make the same mistake they did.

For example, in ‘the porcupine’ we are warned not to accidentally mistake this animal for a ‘comfy-looking’ seat because its ‘spines’, once ‘sat on’ are a painful nuisance to remove. ‘I think I know why porcupines surround themselves with prickly spines’, the speaker explains ‘it is to stop some silly clown, from squashing them by sitting down’. Finally, in typically cautionary tale style, she sums up the key lesson suggested by this unfortunate event: ‘don’t copy me, don’t be a twit, be sure you look before you sit!’ Hilaire Belloc’s The Bad Child’s Book of Beasts, was likely an inspiration for Dahl’s Dirty Beasts with poems such as ‘The Lion’ being comparable to Dahl’s verses in their cautioning of children to steer clear of animals with a vicious intent. ‘The Lion’ is also typical of the traditional cautionary tale’s use of binaries (children are either ‘good’ or ‘bad’) to determine children’s fates. A ‘good child’ will not play, we are told, with the ‘lion’ –and so, presumably will remain uneaten. In Belloc’s Cautionary Tales, ‘bad’ children routinely get their comeuppance whether being burned alive in a fire (as in ‘Matilda’) or being shot when playing with a loaded gun (as in ‘Algernon’) to take two examples. An extra layer of menace is added in Dahl’s work however, in that ‘good’ children, or at least children who have not initially ‘done something wrong’ (and, it should be noted, the good / bad binary is still very much present in Dahl’s work), often suffer too. In ‘The Scorpion’, the child whose ‘rump is stung’ is simply asleep in her bed when the malevolent scorpion pays her a visit. But Dahl does of course ‘do’ grotesquely ‘bad’ characters very well too, as in ‘The Ant-Eater’ when the obscenely greedy ‘Roy’ whose father buys him ‘whatever he desired’ will become supper for the only thing he has not yet acquired, a ‘giant ant-eater’. Indeed, as Klinkenbourg and Cahoon suggest, ‘Cautionary Tales capture so well the fascination children so often find in the grotesque, particularly the humorous grotesque’, and this idea of the ‘humourous grotesque’ is, I would argue, one of the main elements Dahl drew upon from earlier writers of cautionary tales.

For example, in ‘the porcupine’ we are warned not to accidentally mistake this animal for a ‘comfy-looking’ seat because its ‘spines’, once ‘sat on’ are a painful nuisance to remove. ‘I think I know why porcupines surround themselves with prickly spines’, the speaker explains ‘it is to stop some silly clown, from squashing them by sitting down’. Finally, in typically cautionary tale style, she sums up the key lesson suggested by this unfortunate event: ‘don’t copy me, don’t be a twit, be sure you look before you sit!’ Hilaire Belloc’s The Bad Child’s Book of Beasts, was likely an inspiration for Dahl’s Dirty Beasts with poems such as ‘The Lion’ being comparable to Dahl’s verses in their cautioning of children to steer clear of animals with a vicious intent. ‘The Lion’ is also typical of the traditional cautionary tale’s use of binaries (children are either ‘good’ or ‘bad’) to determine children’s fates. A ‘good child’ will not play, we are told, with the ‘lion’ –and so, presumably will remain uneaten. In Belloc’s Cautionary Tales, ‘bad’ children routinely get their comeuppance whether being burned alive in a fire (as in ‘Matilda’) or being shot when playing with a loaded gun (as in ‘Algernon’) to take two examples. An extra layer of menace is added in Dahl’s work however, in that ‘good’ children, or at least children who have not initially ‘done something wrong’ (and, it should be noted, the good / bad binary is still very much present in Dahl’s work), often suffer too. In ‘The Scorpion’, the child whose ‘rump is stung’ is simply asleep in her bed when the malevolent scorpion pays her a visit. But Dahl does of course ‘do’ grotesquely ‘bad’ characters very well too, as in ‘The Ant-Eater’ when the obscenely greedy ‘Roy’ whose father buys him ‘whatever he desired’ will become supper for the only thing he has not yet acquired, a ‘giant ant-eater’. Indeed, as Klinkenbourg and Cahoon suggest, ‘Cautionary Tales capture so well the fascination children so often find in the grotesque, particularly the humorous grotesque’, and this idea of the ‘humourous grotesque’ is, I would argue, one of the main elements Dahl drew upon from earlier writers of cautionary tales.

The idea of a cautionary tale wherein something bad happens to a good child is explored further by Dahl in his story ‘Pig’ from the 1960 short-story collection for adults entitled Kiss Kiss. ‘Pig’ can be interpreted as a cautionary tale in that it warns parents of the danger of ill-preparing a child to deal with the realities of the world.

The recently orphaned Lexington is looked after by his kindly Aunt Glosspan after his parents die having been shot by policemen in a misguided attempt to break into their own house. Glosspan, a strict vegetarian who regards the consumption of animal flesh as unhealthy, disgusting and cruel, firmly embeds these beliefs in Lexington, who is home-schooled at his aunt’s remote cottage; having no contact with the outside world until his aunt’s death. Ill-prepared to deal with the realities of life, Lexington is promptly taken advantage of in every possible way. He is swindled out of his inheritance by his aunt’s solicitor, tricked into eating suspicious meat in a diner, and in the story’s grim finale, visits the slaughter-house in an attempt to determine the provenance of his meal. The story contains various linguistic and stylistic references to Voltaire’s Candide, (itself, incidentally, often interpreted as a cautionary tale about the folly of optimism). But, where Voltaire’s masterpiece concludes with his protagonist tilling his garden, Dahl’s ending is predictably more macabre, with Lexington, being shackled in the slaughter-house before having his throat cut like the titular ‘pig’. The story, in an ironic nod to Candide’s final words in Voltaire’s novel, ends as Lexington passes “out of this, the best of all possible worlds, into the next”.

To turn now to two of Dahl’s most famous children’s novels, Matilda, followed by The Witches. Matilda similarly, is a novel about a child’s struggle to deal with a world in which she finds herself an outsider. Unlike Lexington however, Matilda’s realisation from an early age that adults may be greedy, manipulative and dishonest, instills in her a keen sense of justice that plays out as she teaches the various misbehaving adults (notably her ‘gormless’ and neglectful parents, as well as the monstrous Miss Trunchball) ‘lessons’ in the novel. In the process of this, Matilda utilises cautionary narratives in a manner that demonstrates she is, as Deborah Cogan Thacker contends: ‘knowledgeable about the power of story to have a controlling effect on a listener’. Thacker gives the example of the incident in which Matilda puts superglue inside her father, the bullying and boorish Mr Wormwood’s hat. Explaining to her father about a similar incident to which the episode with the hat appears to owe a precedent, Matilda describes how an unfortunate boy got a finger ‘stuck inside his nose’ with superglue by accident. ‘What happened to him?’ the terrified Mr Wormwood asks; ‘he had to go around like that for a week, he looked an awful fool!’ the gleeful Matilda replies.

Here, power shifts from adult to child then, suggestive of Maria Tatar’s argument that ‘the cautionary tale operates in such a way to provide maximum advantage to the teller’. Such is also the case in terms of the cautionary tale when Hortensia, an older girl, tells Matilda about the headmistress, Miss Trunchball, on her first day at school: ‘I mustn’t frighten you before you’ve been here a week’, Hortensia begins.

Ultimately however again, the power dynamic between Matilda and this ‘all powerful grown-up’ (to quote Dahl), is subverted when Matilda uses her newly discovered skill of telekinesis to knock over Miss Trunchball’s waterjug containing a newt, a creature that terrifies the ‘horrible headmistress’. Although it contains various subsidiary cautionary tales, told by Matilda and other characters in the novel, the novel also has an overarching cautionary message that of, in Thacker’s words, the ‘moral power’ of children and their ability to ‘exact a lasting revenge’ on fools and bullies.

The cautionary warning in The Witches is, comparably to that considered earlier in terms of The Enormous Crocodile, arguably that ‘some people can appear other than they are’; a message that encourages a second glance at things that seem self-evident. As a cautionary tale, The Witches is structurally more traditional than many of Dahl’s other works. There is a rule or ‘issue’ about which the child is warned by his grandmother:

The most important thing you should know about REAL WITCHES is this. Listen very carefully. Never forget what is coming next… REAL WITCHES dress in ordinary clothes and look very much like ordinary women. They live in ordinary houses and they work in ordinary jobs. “Listen,” she said, “I have known no less than five children who have simply vanished off the face of this earth, never to be seen again. The witches took them […]I am trying to make sure you don’t go the same way […]

Luke, the protagonist, inadvertently does find himself involved with a coven of witches after he stumbles upon their convention, suffers the consequences – being ‘smelt out’ by the Grand High Witch before subsequently falling victim to her ‘mouse potion’. As a cautionary tale, The Witches warns in a similar manner to Matilda of the revenge children may ‘exact’ on adults. However, this is explored in a manner that is darker and more ambiguous, the reassuring notion that wickedness has been adequately ‘dealt with’; that a reader may traditionally expect in a children’s book, left out of this novel. ‘I felt sure that all the witches of the world would slowly fade away. But now you tell me that everything is going to go on as before!’ Luke, the protagonist, (whose mouse-status also remains ominously unresolved at the end) comments somewhat concernedly.

Moving from fiction to non-fiction; Roald Dahl’s Guide to Railway Safety brings aspects of the cautionary tale to a real-life context. Commissioned in 1990 (and therefore, one of the last things Dahl ever wrote), by the British Railways Board to respond to rising levels of train-related fatalities involving children, Dahl, and Quentin Blake, set about explaining the myriad things that can ‘go wrong’ when children fail to realise the railway’s potential for danger. The booklet opens with Dahl explaining that: ‘I must now regretfully become one of those unpopular giants who tells you WHAT TO DO and WHAT NOT TO DO. This is something I have never done in any of my books. I have been careful never to preach, never to be moralistic and never to convey any message to the reader.’ Whether or not we entirely agree with his assertion that his writing has never been ‘moralistic’ and is entirely free from didactic ‘messages’, this is interesting because it suggests how aware Dahl was of not wanting to be the ‘all- powerful adult’, or ‘unpopular giant’.

Indeed, as Thacker suggests, Dahl’s ‘tendency’ is to ‘put child characters in powerful positions’ and so, the idea of ‘talking down’ to children was always anathema. In a booklet like this then, where there is a clear and obviously serious purpose to its publication, Dahl has no choice but to tell the reader ‘what to do’ and ‘what not to do’, but, this is effectively offset by Quentin Blake’s typically anarchic and grotesque illustrations, bringing the humour to Dahl’s cautionary warnings in a manner that arguably, strengthens the message. Unlike British Rail’s rather bland, patronising and evidently ineffectual guidance notices that were issued in the years before their decision to ‘get Dahl on board’, Dahl and Blake’s pamphlet demonstrate the grisly consequences of what might happen if one fails to abide by these rules. Nothing says ‘don’t poke your head out of the window of a moving train’ quite like a decapitation!

Dahl once revealed his surprisingly traditional view that adults – presumably including children’s authors! – were part of the process of ‘the relentless need to civilise this thing that when it is born is an animal with no manners, no moral sense at all’. Of all children’s stories, cautionary tales with their inherent sense of the moral and the didactic, epitomise such a view. However, as we have seen, Dahl also broke with the traditional tone and structure of this genre, innovating upon, and injecting into it, a new sense of raucous energy. In his children’s books, Dahl does engage in the ‘civilising’ process he describes, but his books are at their most mesmerisingly alive when he disrupts and distorts such a project, in a way that involves children directly in the process of telling, and endows his child characters with strategies to challenge adults who behave in ‘monstrous’ ways. In this way, Dahl’s re-integration of facets of the cautionary tale into such narratives is, I would argue, key to Dahl’s creation of a voice and style that remains synonymously his own.

This piece was originally published as part of Wales Arts Review’s collection, Roald Dahl | A Retrospective.