2022 marks ten years since the launch of Wales Arts Review, and as part of our celebrations, throughout this year we’ll be revisiting some of the best and most loved features, interviews, and reviews from our archive of nearly five thousand published pieces.

The Urdd’s National Choir, Côr yr Urdd, recently took a trip to Birmingham (Alabama) as a part of an ongoing transatlantic partnership. Today we take a look back at the origins of that relationship, revisiting a piece by Cerith Mathias telling the story of a Welsh campaign to replace a window following the bombing which killed four black children at the 16th Street Baptist Church on 16th September, 1963.

*

The sky looms low, heavy with dark cloud as I step from the car into the humidity of a deserted parking lot. The hot air crackles with the promise of a downpour; often the fare, or so I’m told, of a mid-September morning here in Birmingham, the largest of Alabama’s cities. The streets are unexpectedly empty, an almost eerie quiet reverberating from the gleaming-grey pavements. A befitting first glimpse, perhaps, of where, this year, the painful events of the past are being ushered to the forefront of the present.

The street on which I am standing was at the heart of the Civil Rights Movement of 1960’s America; the concrete underfoot once pounded by the soles of marching children and baton wielding police officers. Dr Martin Luther King’s calls for non-violent protest in what he dubbed ‘the most segregated city in the US’ were met on this very corner with water cannons and the snarling jaws of police dogs. And in the Baptist Church, here on Birmingham’s 16th Street, the lives of four young girls were snuffed out by a racist bomb attack.

The horrific events of that day would prove a turning point in American history and the actions of one Welsh artist and a campaigning newspaper editor forever linked Wales with the struggle to be ‘Free in ’63′.

The morning of September 15th, 1963 began much like the day of my visit.

‘It was a typical Sunday morning at my household,’ recalls William Bell, who was 11. Now Birmingham’s Mayor, he is the fourth African American to hold the office in the city, something unimaginable at that time.

‘It was a dreary day, not really a sunshine day but overcast… my mother woke everyone up for breakfast… then we began the process of getting ready for church.’

As his family was about the leave the house, he remembers a loud noise ‘that was like nothing that we’d heard before… it was a strange noise. Everything seemed to get quiet and the world seemed to stop.’

Moments earlier, on the other side of town, as her friends came to the end of their Sunday school class, 15 year-old Carolyn McKinstry answered the ringing telephone of the 16th St Baptist Church.

‘Three minutes’ said a male voice before hanging up.

McKinstry reportedly replaced the phone receiver in its cradle and made her way into the next room. She’d taken around 15 steps when, at exactly 10.22 am, a bomb exploded near the church basement, tearing violently through the large stone building, destroying its steps, shattering its windows and spilling rubble and glass out into the street. The face of Jesus in the church’s main stained glass window was blown clean out.

Jim Lowe, who was 11 years old, was with his classmates in a room three doors down from where the bomb had been planted. He knew all four girls who perished.

‘I remember a loud deafening noise and seeing glass flying out of the windows’ he tells me.

‘My ears were ringing and I could hear muffled voices yelling and screaming… I had no idea what was happening.’

Inside the church were nearly two hundred congregants, mostly all children, attending Sunday school. Around 23 were injured. Four were killed instantly. The bodies of 14 year-olds Carole Robertson, Addie Mae Collins and Cynthia Wesley, along with 11 year-old Denise McNair were found huddled together under the twisted debris.

‘I don’t remember how I got to and from church that day’ says Lowe, who is now the Bishop of the Guiding Light Church in Birmingham.

‘The one event seems to have overwhelmed everything else.’

Racially motivated bombings were not extraordinary at that time, with nearly fifty unsolved incidents taking place from the late 1940s through to the mid-1960s – earning the city the nickname ‘Bombingham’. This, however, was the first to result in the loss of life.

The months leading up to September 15th had been tumultuous. The church, at the centre of Birmingham’s black community, was the headquarters of the local civil rights movement. In May that year, it had become the organising centre of the children’s crusade, a campaign that produced the Birmingham Accord, which sanctioned, amongst other things, the desegregation of lunch counters, public bathrooms, fitting rooms and drinking fountains.

Martin Luther King proclaimed ‘…the walls of segregation will crumble in Birmingham and they will crumble soon.’

On August 28th 1963, just a fortnight before the 16th Street bombing, King shared his dream with over 200,000 people who had marched on Washington. Tension rippled through Birmingham’s streets.

Alabama’s high profile, outspoken pro-segregation Governor, George Wallace stood firm in his prejudice, telling The New York Times in order to stop integration, the state needed a ‘few first class funerals.’

A week later, a small splinter group of the Ku Klux Klan, the Cahaba Boys, enacted Wallace’s rhetoric by planting a box of dynamite beneath the steps of the 16th Street Baptist Church; its detonation forever slashing a deep, ugly scar on Birmingham’s timeline. Despite the biggest FBI operation since the pursuit of bank robber John Dillinger in the 1930s, it would take another forty years before the bombers were brought to justice.

The tragedy altered forever the course of the civil rights movement, according to many, acting as a catalyst for the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

‘They became martyrs,’ Bishop Lowe explains. ‘Their deaths started a movement for change that could not be stopped… That explosion ignited an even greater explosion – an explosive movement that changed the heart of a nation.’

America was not alone in her revulsion. Across the Atlantic, in the small Carmarthenshire village of Llansteffan, news of the injustice was met with indignation by Welsh-based artist John Petts.

In a series of interviews, archived by the Imperial War Museum, the artist, who died in 1991, recalled hearing the news on the radio.

‘Naturally as a father I was horrified by the death of the children. As a craftsman… I was horrified at the smashing of all those windows, and I thought to myself: my word, what can we do about this?’

Petts contacted David Cole, the editor of The Western Mail suggesting a fundraising campaign to replace the church’s main stained glass window as ‘…a gift from the people of Wales. A national gesture of goodwill.’

The following day, the paper launched the campaign with the headline ‘Alabama: Chance for Wales to Show the Way.’ More than 3,000 people donated no more than half a crown each, as per Petts’ stipulation. Within days the £500 target had been reached, with the fund closing at £900.

‘Photographs were shown of children both black and white in the Cardiff Docks area queuing up at the Western Mail offices handing over their pocket money,’ Petts recalled.

‘And within a short while the fund was closed and I found myself flown over to Alabama… They had never heard of Wales, had no idea where it was, but they very quickly were told something of the little country Wales.’

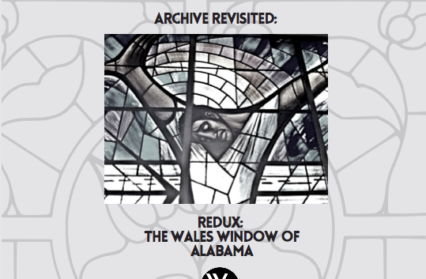

Petts’ bold design for what has become known as The Wales Window depicts a black Jesus ‘…a suffering figure in a crucified gesture, with one hand flung wide in protest, the other in acceptance.’

Written underneath are the words ‘You Do it to Me’, inspired by the words of Jesus in Matthew 25:40:

Inasmuch as ye have done it unto one of the least of these my brethren, ye have done it unto me.

Back in the Birmingham of today – it’s the result of that gesture of fellowship that I’m here to see.

The 16th Street Baptist Church is an imposing building. It stands broad and solid occupying the corner of 6th Avenue North and 16th Street. Walking up its stone staircase, it is difficult to marry the structure before me with the images of devastation from fifty years ago. Opening the heavy wooden doors I’m met by the church’s custodian, Richard Young, along with the clatter and chitter-chatter of cleaners and workmen. Only a few days previously the church was host to a ceremony commemorating the events of 1963, a service so well attended, Young says, that it was ‘…packed out. We even had a screen over in the park opposite, because so many people wanted to come and be a part of it.’

Richard Young is a lifetime member of the church, which he tells me has an active congregation of almost two and a half thousand. Though his own personal history is deeply interwoven with that of 16th Street – he has his own seat for Sunday services, which he jokes that ‘no one can sit in if I’m not here’, he however narrowly missed ‘…that terrible, terrible day.’

The afternoon before the bombing, Young left Birmingham for college, enrolling in the historic Tuskegee Institute, located around two hours’ drive south of the city.

‘I couldn’t believe what had happened’, he says of hearing the news:

One of the girls lived around the corner from my family – we were friends. It hurt me. A lot of people were very upset; there was a lot of hurt for a long time.

I follow Young down to the basement, watching as he runs his hand along the wall as we walk, patting the smooth white plaster gently every now and again. We enter a large room filled will folding chairs and tables, still used for Sunday school classes. At the back, behind a small partition, are some of the objects rescued from the church following the blast; a clock stopped at exactly 10.22 am, the telephone answered by McKinstry along with framed pictures of the events of the civil rights movement. On the wall, hangs a yellowing copy of The Western Mail from 1964, complete with Petts’ charcoal designs for the window. In a glass case underneath sit four stones painted with the names of the four girls.

We move back upstairs to the main hall, a bright, light-filled room, where row upon row of wooden pews sink comfortably into the pile of a deep red carpet. A balcony with further seating hangs overhead. Young raises his eyes, and nods upwards towards the centre balcony. There in a dazzling haze of purples and blues stands The Wales Window.

Chuckling at my reaction, Young says ‘Yep, it’s a beauty all right.’

More vibrant and intricate than any photo could ever do justice, Petts’ window is truly breathtaking. Above the figure of Jesus, arms outstretched, curves a rainbow constructed of tiny pieces of blue, purple and pink glass – representing racial unity. The daylight streams through, making kaleidoscopic patterns on the carpet.

What does Richard Young know of the story behind the window I wonder?

‘I remember that the children in Wales wanted to give the pennies they had to us,’ he says.

‘And the window was a symbol here of their love for us when we were suffering. It really means a lot to the church.’

Many events are taking place in Birmingham throughout the year to mark the 50th anniversary of that fateful day. The weeks preceding my visit have been especially busy. In addition to the service at the 16th Street Baptist Church, prayer meetings, and talks have also been held. A website – Kids in Birmingham 1963 – has been established as a platform for all; white and black, who were children at the time to share their experiences. And a further piece of art commemorating the lives lost has been unveiled in the city.

Sculptor Elizabeth MacQueen’s Four Spirits – life-size statues of the four little girls – stand in the gateway of Kelly Ingram Park, directly opposite the Baptist Church.

MacQueen, herself from Mountain Brook, just outside Birmingham, was 14 at the time of the bombing, the same age as three of the girls who died.

‘It bored a hole in my psyche for justice,’ she tells me.

MacQueen’s artwork depicts the girls playing and reading – all four are engrossed in an activity of some sort, bringing the statues very much to life. While researching her design, she became close with Carolyn McKinstry, who had been talking with the girls in the church’s basement, immediately before going to answer the telephone.

‘They were all friends and I saw them talking together and getting ready for their service upstairs,’ MacQueen says.

‘Carolyn told me Addie Mae was tying the bow on the dress of Denise… Carole was a Girl Scout, so I have her saying “Come on y’all we are late!” Cynthia was the child of teachers, she loved reading.’

Indeed, Cynthia Wesley, the only one of the four statues who is seated, is depicted reading WB Yeats’ The Stolen Child.

‘I wanted a quote that was original if possible’ states MacQueen:

It took me nights and nights. I looked at so many quotes, including Ralph Ellison, Maya Angelou – on and on into the nights. Eventually someone sent me The Stolen Child and I wept. That was it.

Elizabeth MacQueen’s statues are not the only ones that inhabit Kelly Ingram Park. The small square of green has its own difficult story to tell; often the location of police water cannons and vicious attack dogs used against civil rights campaigners. These events are also immortalised in stone here, as is another martyr of the movement, The Rev Dr Martin Luther King. In the shadow of the 16th Street Baptist Church, he stands at a distance, but directly behind the four girls, a watchful parent presiding over innocents at play.

Walking amongst the shrubbery and sculpture, as the first fat drops of rain, overdue from the morning, start to fall, the value of art in not only recording and honouring events like those of September 15th 1963, but of also healing the pain caused, is incredibly apparent.

‘In my work, I have fought and shouted aloud against the evil of violence – especially with the Alabama window,’ John Petts once told a reporter.

From my conversations with the people affected – those who survived and lived through those events – Petts’ voice has been heard loud and clear.

‘The people of Wales showed they cared in a tangible way, even if people here did not,’ says Bishop Jim Lowe.

‘That impression upon me as a young child was very important to help me eradicate the belief that hatred against me and my people was not as widespread as I had been led to believe.’

Cerith Mathias ‘The Wales Window of Alabama ’ was first republished by Wales Arts Review in 2020.