David Sherwin died January 18th 2018 at the age of 75. He has a permanent place in the highest pantheon of British cinema. He was scriptwriter for a trilogy of films that has no like. All three were directed by Lindsay Anderson and had Malcolm McDowell in the lead as the same character, Mick Travis. If.… in 1968 was the trailblazer. O Lucky Man! five years later was less classic 1960s, more picaresque and surreal. Britannia Hospital in 1982 was a no-holds-barred satire in which the stressed-beyond-hope establishment is metaphor for the nation. The Daily Telegraph loved “the exuberance of the comic invention.” Sherwin was delighted to see that it drove British guests to storm out of its screening at the Cannes Film Festival. “Success!” he wrote.

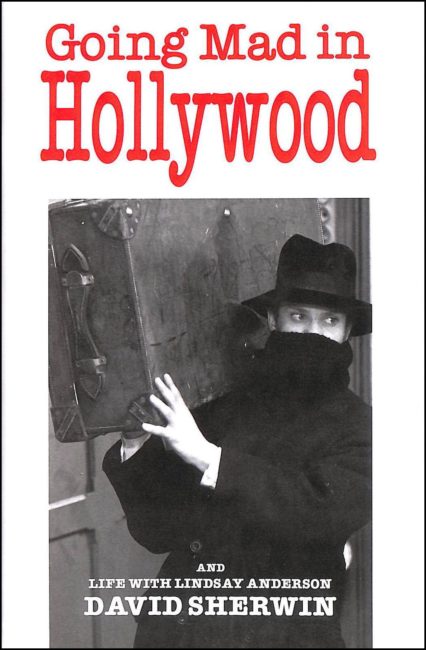

The episode appears in his book Going Mad in Hollywood. As with films there is no book of film that is its like. Rereading it in 2018 is to experience a book of vibrant observation that jumps off the page. It is a chronicle of persistence, adamantine youthful self-belief, ascent, instability and fall to near-penury. Alcoholism and mental health issues were ever background in the life.

The episode appears in his book Going Mad in Hollywood. As with films there is no book of film that is its like. Rereading it in 2018 is to experience a book of vibrant observation that jumps off the page. It is a chronicle of persistence, adamantine youthful self-belief, ascent, instability and fall to near-penury. Alcoholism and mental health issues were ever background in the life.

Going Mad in Hollywood is in the form of an intermittent diary that runs from May 1960 to May 1996. Sherwin attended public school and at Oxford he and a friend are determined to turn loathing for it into a screenplay. Its title is Crusaders and his attention to it is all consuming. He fails his first year Oxford exams and has to tell his historian father. May 1960 is a busy month. On the 17th Margaret Ramsay, theatre’s leading agent, says she wants to meet. On the 21st he is presenting to a leading film producer, Lord Brabourne. “The noble lord is straightforward,” records the diary. Crusaders is the most evil and perverted script he has ever read. It must never see the light of day. I visit another well-heeled producer, Ian Dalrymple, who had been head of the Crown Film Unit. He says we should be horse-whipped.”

A letter to Hollywood brings results. On November 15th 1962 an airmail letter arrives. The sender is Nicholas Ray. He’ll be staying at the Grosvenor House Hotel. He would like to meet me to discuss Crusaders. The meeting has its comic moments but the twenty-year old leaves in the belief that his film is to be directed by the master Ray. 24th February 1963 an aide from the USA informs him that the director has suffered a nervous breakdown.

On July 10th July 1966 everything changes. Sherwin is in the Pillars of Hercules pub in Soho. He meets Lindsay Anderson. Their conversation touches on Woyzeck. “With this mutual flash of understanding our destinies change.” Seth Holt is also there. “He will pay me £20 a week. So I become a real scriptwriter.” So it begins in earnest and in March 1969 he is in New York. “I stare at the story in Variety, not quite believing it is true.” The story reads “SHERWIN WINS BRITISH WRITERS’ GUILD AWARD.”

Two months on he is in Cannes. The entry for May 13th reads. “The British Ambassador arrives foaming with fury. If… is an insult to the nation and must be withdrawn from the Festival. Lindsay replies that it is an insult to a nation that deserves to be insulted and tells the Ambassador to bugger off. Besides it can’t be withdrawn; it is the official British entry.”

The ascent continues. O Lucky Man! gets great reviews. The critic Judith Christ calls it the best in the decade since Dr Strangelove. The Sunday Telegraph calls it “entertainment on a prodigious scale.” In 1975 a power agent in Hollywood tells him that Scorsese has named Travis Bickle after Mick Travis.

The diary covers the colour, the volatility and the harshness that are the industry of his choosing. August 1981, the writer sends a script to his director with the diary record: “I have filled it full of blood, humour and dramatic extremism. I have tried to patch the holes in the plot.” The following day “Lindsay rings – it’s incoherent and dreadful.” On the 19th of the same month he meets a drunken advertising executive. “If… was f***ing parochial,” he is told. O Lucky Man! was shit and “Lindsay couldn’t direct two actors in a shoebox.”

The decade goes badly. May 4th 1988. “I go down to Lydney to sign on the dole.” It is the beginning of a series of anguished encounters with government employees. 20th December: “The bottom falls out of our rusty 13-year old car. Now we are carless. A cheque from the DHSS desperately needed.” March 29th 1992: “We’ve no money.” A sequel to If… is floated with a script payment of $250,000. It never happens. The book ends on August 30th 1996 with a posthumous letter to Lindsay Anderson. Its last words run, “But I will carry to my grave the words you spoke at the beginning of Britannia Hospital. Only three things are real: God, human folly and laughter…”

There is, in truth, in Going Mad in Hollywood little of the first or the third. But the second with its attendant disorder is there in full. As a book it is an essential companion to a re-watching of the films.