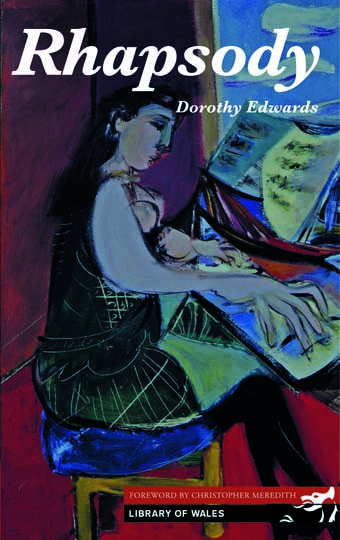

Continuing his journey through the Library of Wales collection, Jon Gower now considers a selection of short stories in his review of Rhapsody by Dorothy Edwards.

In a recent Guardian interview the British novelist Rupert Thomson suggested that:

Fiction essentially teaches you to understand and empathise with other people. That’s important. I think fiction is related to ethics in that you step out of your skin and become someone else for the period you are reading the book. And it is a short step to extrapolate from that to the teaching of compassion.

I took these thoughts with me into a reading of the artful, economical short stories marshalled into Dorothy Edwards’s Rhapsody, first published in 1927. These terse and ironic tales seem to teach us very little about compassion, or much about human warmth and connectedness for that matter.

by Dorothy Edwards

The ten stories that make up Rhapsody – with an additional three bonus tales in this LOW edition – do not make for empathetic fiction, yet they are undoubtedly fine works, taut and elegantly wrought narratives with never a single word wasted. They are always, unutterably refined, yes, that’s the word, very refined.

They introduce a parade of characters, often very similar ones, who seem to drift from one tale to the next, from one country house setting to the next, consistently failing to connect, to exchange the least vestiges or degrees Fahrenheit of human warmth, let alone any modicum of love. They are tales of moments when two people almost connect, like that scene in the film Witness where the city detective dances around the Mormon girl, their lips tantalisingly close, but never fully meeting. And in Edwards’ chill waltzes, even when members of the opposite sex do get close enough to kiss, and do, even that act is devalued, or dismissed as somehow meaningless.

The stories are formulaic, with the basic plot line taking a visitor to a country house, usually an older man where he encounters a young girl who attracts him but then nothing comes of it.

So often, nothing comes of it, the basic human attraction: even in tale such ‘A Country House’ as where jealousy flashes a pair of emerald green eyes when a husband grows wary of an engineer, Richardson, who comes to install electric light to his home and spends lots of time with the wife, the love “action” is ultimately a damp squib, as the engineer fails to fully declare himself, or show his feelings.

The formula extends to pretty much each story featuring a garden, often planted with laurels and rhododendrons, and music too, as the title of the collection suggests. Dorothy Edwards was herself musically gifted, so it’s little wonder that there are many music lessons and piano recitals and drifts of melody wafting through the settings along with the smell of yellow roses. So a curious young man called Froud plays Beethoven with inspiration, and a German lady called Miss Wolf plays the violin and breaks some hearts at a weekly music club.

Dorothy Edwards is very good at emphatic openings. ‘Sweet Grapes’ starts thus: ‘My friend Hugo Ferris decided, a few summers ago, to taste to the full the pleasures of solitude…’ while ‘Summer-Time’ states that ‘The most foolish things happen to people in summer.’ That last might not be a bad summation of the import of Edwards’ stories.

A shadow falls over each page of this collection, knowing that the author’s life was short and painfully starved of love. Edwards died at the age of 31, taking her own life on the railway tracks near Cardiff in 1934. Her suicide note has more than the usual chill about it: ‘I am killing myself because I have never sincerely loved any human being all my life. I have accepted kindness and friendship and even love without gratitude, and given nothing in return.’

That note acts as a revealing gloss on Dorothy Edwards’ stories, ones so often puzzling themselves, almost indolently about humans failing to love, or fall in love, or missing even the remote possibility of doing so before going their separate, lonesome, lonely ways.