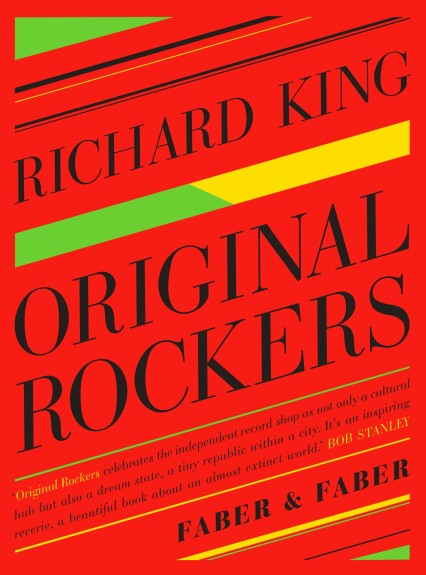

Craig Austin talks to Richard King about his latest book Original Rockers, the very personal nature of his unique homage to the record store.

Original Rockers, one of this year’s most beguiling books to date, deserves better than to be conveniently filed away in the narrow and limiting preserve marked ‘record shop’. Instead it exists as a memoir of an absent past; one that wilfully defies classification, taking in as it does broad metaphysical themes of landscape, time, and at its heartfelt best, personal loss. It inhabits an otherly place; one wholly in keeping with its subject matter, a world away from the restrictive and often regressive backwater forever tainted by Nick Hornby’s cosily orthodox scrapbook of lists about lists about lists. It’s a trap that its author, Richard King, a Welshman who has worked at the heart of the independent music industry for nearly twenty years, was never likely to ever cultivate or fall victim to:

Original Rockers, one of this year’s most beguiling books to date, deserves better than to be conveniently filed away in the narrow and limiting preserve marked ‘record shop’. Instead it exists as a memoir of an absent past; one that wilfully defies classification, taking in as it does broad metaphysical themes of landscape, time, and at its heartfelt best, personal loss. It inhabits an otherly place; one wholly in keeping with its subject matter, a world away from the restrictive and often regressive backwater forever tainted by Nick Hornby’s cosily orthodox scrapbook of lists about lists about lists. It’s a trap that its author, Richard King, a Welshman who has worked at the heart of the independent music industry for nearly twenty years, was never likely to ever cultivate or fall victim to:

‘In my mind I was trying to write a nature book about a record shop,’ he tells me. ‘I’d read too many nature books about men jumping into lakes and I just thought that the strangest place I’d ever known was Revolver Records in Bristol. It was far more mysterious than any of these places where men were jumping into lakes. I also realised how unlikely it was that a place like that could ever happen again and I wanted to try to capture something of the atmosphere of the shop, but also to try to capture the atmosphere of the city at the time, and what had gone before and come after.’

Having worked at the shop during the early nineties, not long after a recession, and in a city that by reputation is never likely to run for a bus, it’s equally clear that the autonomy that was afforded to King at the time is unlikely to be replicated any time soon. ‘One doesn’t want to get nostalgic about hard economic times,’ he reflects, ‘but the sense of freedom was very palpable. It was a shop that only took cash or cheque. There was no credit card machine, no chart return system, so it seemed to represent something more than just a record shop. It represented more than just music, a way of being able to operate and interact with people that was just extraordinarily free’.

There’s an element of defiance about the ethos of Revolver, one perhaps best embodied by its belligerent and mercurial proprietor Roger, that Original Rockers positively radiates, a welcome evocation of what it once meant to be truly ‘alternative’, a term that has been diluted to the point of obsolescence in recent years. ‘It was definitely a defiant place,’ Richard recalls. ‘It was defiant in terms of the music it sought to push on people, we played a lot of free jazz and tried to sell that to people with mixed results, but it definitely dealt in music that existed in the margins. We stocked a lot of difficult music, a lot of music not played by white people with guitars, it was undeniably something of an underground headquarters but no-one knew quite what it was or what it meant. It was definitely some kind of psychic frontline and I know that everyone who went there felt the same. It had the spirit of, not so much an anarchist bookshop, but certainly an esoteric bookshop. When you walk into these kinds of places you almost make a contract with what’s on the shelves, with the people who work there, and you’ve probably also made a contract with yourself. A contract that represents the kind of life you want to live, and I think all of those things, subliminal or unconscious, were there every day’.

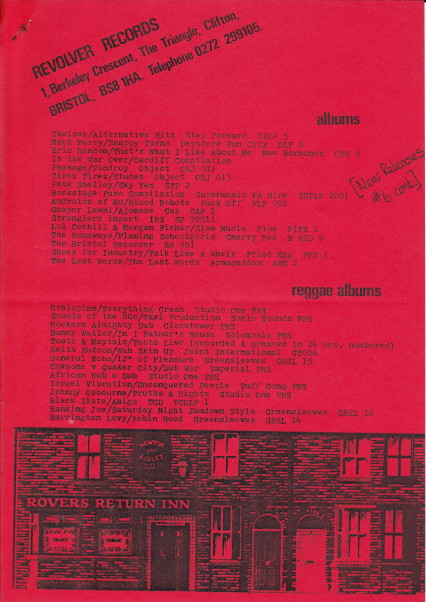

Richard talks both within the book and in conversation about what he describes as the ‘hieroglyphics’ of the shop, the clandestine signs and symbols that gave Revolver its own unique sense of otherness. ‘There seemed to be lots of secret codes lying about the place, constant reminders of the past; at least in my imagination.’ The faded scrawl of both John Peel and The Cure’s Robert Smith, the detailed sets of markings on the shop’s paper master bags, the cave-like vinyl decay of the infamous ‘back room’; all of these things contrive to create an evocative sense of sensory archaeology.

In a similar vein, the author talks of stumbling across an aged press release citing the ‘new release’ of a Keith Hudson reggae album having only just spent the previous day putting out a new version of the same record on its reissue: ‘The record wasn’t even that well known but seemed to be part of the shop’s gravity. It did colour the atmosphere. It was hard to escape the pull of the shop’s past, a conceivably more commercially successful past than the one that I experienced. The very back room in particular’- a relic of the Cartel distribution group, one in which water had damaged all of the records – ‘…provided a rich sense of both the shop’s history and of how music ages and gets treated. How it gets forgotten over time.’ Nonetheless, this evocation of history is not one that the author ever permits to stumble into the corrosive realm of nostalgia, a snare most skilfully negotiated towards the book’s conclusion; a series of emotive passages in which Richard revisits the empty whitewashed shell of the space that Revolver once inhabited. ‘If people find it evocative or elegiac then I’m thrilled that they do but I really went out of my way, to try as hard as I could, to avoid making it nostalgic. When you reach the age of 40 it’s very easy to fall into that trap, and nostalgia is quite a dangerous emotion. I quite enjoyed visiting that space and feeling absolved of that. I felt like I’d chosen to confront the past before it could curdle into nostalgia.’

Though the travails of Revolver take in maverick influences as wide ranging as Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry, Can, and Julian Cope, it is the seemingly incongruous figure of Rod Stewart who plays an inadvertently influential role in some of the book’s most personal and tender recollections. ‘I absolutely love Rod Stewart. But I don’t love Rod Stewart in a “I like pop music” way,’ Richard laughs. ‘I like Rod Stewart in a three-day-week, Newcastle Brown Ale binge way. That’s the way he made those records.’

It was Rod whose unmistakable pipes formed the backdrop to a teenage travelogue embarked upon by King and his friend Joshua Compston. Compston, who would later die in tragic circumstances, worked alongside the key players of what ultimately became the ‘YBA’ movement, a loose group of conceptual and visual artists spearheaded by the likes of Tracy Emin and Gavin Turk.

‘When you encounter death for the first time,’ Richard explains, ‘especially as a young person, you’re not really equipped to cope, and I do associate learning about Joshua’s death with being at Revolver, so I thought that while my memory is still functioning I’d like to take the opportunity to pay tribute to him. He was a very influential person and people have increasingly started to write him into the narrative of that movement. He was an extraordinary person, extraordinarily difficult at times, but it felt appropriate to reflect Joshua’s life and our friendship, given that I was attempting to write about music as a personal experience, and given that I’d forgotten myself about what music as a personal experience actually was. Once I began writing and realised that it would be such a personal book I thought that there would be little point in writing about listening to records without the wider context of life. So I made the decision that that was how I would approach the entire thing. Losing a friend when you’re so young is something that lodges firmly in the memory and I associated it with being sat on the stool in the shop. So I thought I’d better grab the nettle and seek to get to the bottom of what he meant, not just to me, but also to all those people he helped, and whose careers he helped. I had some extraordinary times with him and I wanted to capture a life that was cut so short with the added perception that the passing of time provides. He was a wonderful man in so many ways. His funeral was attended by absolutely every single person who went on to have a career in White Cube. Gavin Turk even painted the coffin, yet it was all over before that scene really began. There’s always one of those figures in every major scene.’

The author’s desire to avoid nostalgia doesn’t necessarily translate into an unquestioning embrace of either the contemporary British high street or the nauseous London-led repackaging of an evidently urban area as some kind of ‘village’: ‘These days you get these shops that think they’re selling expensive esoteric things, yet a record shop can sell a genuinely esoteric thing very cheaply and it‘s a shame that those places aren’t seemingly allowed any more. If it opened now, Revolver probably wouldn’t be a Costa Coffee because it was based in Clifton. It’d probably be some kind of independent boutique coffee joint instead, the kind of place that would have expensive esoteric things on the wall, but wouldn’t have them on sale for a fiver. Not in the way that a record shop can.’

That the very notion of a record shop can occasionally seem as anachronistic as the notion of vinyl itself once did says much about the transitory surface-driven YouTube culture of 21st century Western society. That such a feeling can also be experienced by a man who once spent his early twenties ostensibly engaged in the practice of listening to an entire record shop would seem to offer little hope for the rest of us. Yet what it has resulted in is that most peculiar of things; a world of abstract dreams assembled from the remnants of one man’s memory, a book about a fundamental failure to engage already having proven itself to be one of the year’s most engaging books.

Archive Revolver ephemera courtesy of Richard King.