Adam Somerset applauds a radio feature on naturalist R.M. Lockley.

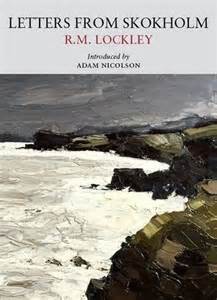

I Know an Island is a documentary tribute to the naturalist Ronald Lockley. It is a beautifully modulated blend of human voice, natural sound and a small element of music. It was broadcast intriguingly on the evening of Easter Sunday (and is now available on iPlayer). The desacralisation of culture has been a move in line with an estrangement from nature. The rituals of faith waxed in harness with the pastoralisation of human society, the passage of the seasons providing the base rhythm for both. Presenter Jon Gower ends his programme with an observation of simplicity. Lockley was a pioneer in field ethology although the term is one bestowed by posterity. His unlocking of the secret lives of bird and animal was done, says Gower, through observation and patience. His definitive work on the Manx shearwater took twelve years. It is the demeanour and temper required of all ornithologists, attributes that induce in its participants calm and wonder. The scheduling of Easter Sunday then was fitting. Nature and divinity are alike in their evocation of an immanence that transcends the transience of the hour.

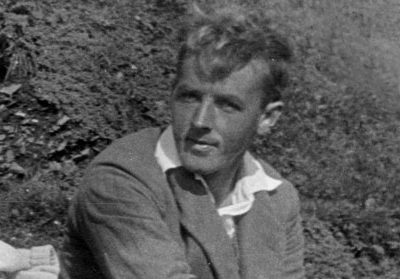

Ronald Lockley was born November 8th 1903 and he died April 12th 2000. His ashes were scattered in the sea off the island of Skokholm. That determining point in his life occurred early. In 1927 he took on a lease for twenty-one years of the island, one of the cluster of island rocks several miles off the Pembrokeshire coast, an often rocky journey from Milford Sound. His residency lasted until Skokholm’s requisition by the military in wartime. The Spartan life was no disincentive and he acquired the abilities to sail and build. He found a soulmate in his wife, Doris. But he soon discovered that to make a living from selling rabbits and breeding chinchillas was not easy. The talent to turn the materials of his life into writing resulted in a profusion of output. More than sixty books ensued, part of the torrent that ran the range from regular journalism for The Countryman magazine to scientific papers.

Ronald Lockley was born November 8th 1903 and he died April 12th 2000. His ashes were scattered in the sea off the island of Skokholm. That determining point in his life occurred early. In 1927 he took on a lease for twenty-one years of the island, one of the cluster of island rocks several miles off the Pembrokeshire coast, an often rocky journey from Milford Sound. His residency lasted until Skokholm’s requisition by the military in wartime. The Spartan life was no disincentive and he acquired the abilities to sail and build. He found a soulmate in his wife, Doris. But he soon discovered that to make a living from selling rabbits and breeding chinchillas was not easy. The talent to turn the materials of his life into writing resulted in a profusion of output. More than sixty books ensued, part of the torrent that ran the range from regular journalism for The Countryman magazine to scientific papers.

The programme brings together a range of complementary voices to illuminate the man and the life. Jon Gower makes the journey to Skokholm and we hear the sounds of Manx shearwaters, Atlantic puffins, European storm-petrels. An island is particular, says an early voice. It brings that heightened awareness of tide and wave. Amy Liprot, a native of Orkney, is a contributor and Lockley made visits to Bardsey, Heligoland, the Blasket Islands. As for Jon Gower he and Skokholm go back to when he was a night-time volunteer observer at the age of fourteen. He had been a reader of Lockley at thirteen and admirer of the “clarity and perennial sense of wonder at the order and beauty of things.” The documentary has a purpose: “I’m travelling back to the source of his ideas.”

Gower’s voice is light and the programme is woven with acquaintances from the life, Lockley’s son, and a scholarly authority. Lockley’s own voice appears. His unintended celebrity brought him to Desert Island Discs and a small piece of Debussy is heard. David Saunders recalls the man and reads a piece of the prose on sea birds. Richard Adams, for whom Lockley on rabbits was crucial, calls him a “most distinguished ornithologist” whose knowledge was wholly self-taught. There is an element of right timing to scientific accomplishment. When Lockley began little was understood about the migratory patterns of sea-birds and the programme touches on the experiments. A bird released in Cambridge is back at its island home by nightfall. Shearwaters taken to Boston, Massachusetts and Istanbul make their way unfailingly to Skokholm.

Gower cannot compose a sentence that does not sing. On the island he is present to see “day yielding into night” and “a cavalcade of gulls.” He recalls the improbable route to celebrity. A Balkan monarch arrives on the lonely rock with much ceremony. The film-maker Alexander Korda appears and the result in 1934 is The Private Life of the Gannets which wins an Oscar. Julian Huxley steals the main credit. When the two meet much later in the 1960s Huxley offers to give him the Oscar but by this time Lockley has reconciled himself with his once collaborator. His legacy was not just literary. His was the first British bird observatory, established in 1933, and they are now ubiquitous.

The voice of Damien Walford Davies is threaded throughout in assessment of the cultural significance. Lockley was guided by Thoreau and may have been known “as the loneliest man in Britain”. But, says Walford Davies, it was “not running away but finding absolute connection with wider communities.” On the prolific outpouring he says “you cannot write islands in one script”. The multiplicity of genres is mandatory, the blend of scientific objectivity and subjective immersion in non-human life an essential part of it. He does not write from a perspective of hierarchy of phylogeny. He wants to see the human and natural together. In his view Lockley was “ahead of his time, he’s a global thinker and he has a lot to tell us in 2017…he writes nature, he thinks across borders, he is an archipelagic writer, he thinks in a series of linked places, in that sense he is a great unifier.”

I Know an Island: R M Lockley eschews the fads and follies that regularly disfigure the BBC’s attempts to make documentaries. It is a credit to all involved in its making.