Through analysing literary responses to the 1994 genocide in Rwanda, Sophie Buchaillard explores the role of fiction in giving a voice to silence. This process inspired her debut novel Victoria; a partially autobiographical tale of two teenage girls, one in Paris, one in Rwanda, and the gap left by their interrupted correspondence.

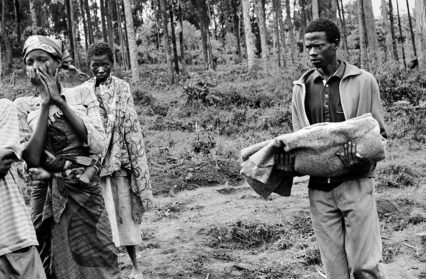

When reality is too hard to bear, or the topic too close to the bone, it is in our nature to find ways to distance ourselves. In doing so, there is a risk we become emotionally anesthetised, to the point of denial. As I sit in my kitchen listening to the morbid daily count of COVID-19 victims on the radio, I am reminded of how figures give death an abstract texture, dehumanising the horror. This was the case with the third genocide of the 20th Century. In 1994, the International Community spectated for 100 days the systematic extermination of 800,000 Rwandan Tutsis (and their sympathisers). Its reaction was one of global indifference. I was sixteen years old at the time and for a few months, I corresponded with Victoria, a girl my age who had fled Rwanda for the refugee camp of Goma, in neighbouring Zaïre. One day she wrote that she was being moved. I never heard from her again. At the time, a man involved in the team that organised the controversial French response told me nothing could be done. I believed him. He was my father. In looking for answers, I found that fiction provided me with a prism through which to look, without losing the emotional attachment to individual stories. Characters became my guides, enabling the telling of an unthinkable story.

In my creative practice, the theme of social injustice has always been pronounced. I write to make sense of the unthinkable. When I started to write about Rwanda, I had originally intended to explore the loss of identity experienced by female trauma victims who have suffered displacement, and the healing power that narration can have on taking back control of the story, but Clementine Wamariya has done this better than I could in The Girl Who Smiled Beads. A first-hand account of her journey from a refugee camp in Rwanda to the United States. Researching what happened in Rwanda, I found gruesome witness accounts recorded by Philip Gourevitch’s We Wish To Inform You That Tomorrow We Will Be Killed With Our Families. I found the investigative reporting of Linda Melvern’s A People Betrayed, who best articulated what happened, why, and who ought to be held to account. Twenty-six years on, we know that what the world press portrayed as a spontaneous tribal conflict was in fact the result of a carefully planned policy of fearmongering and dehumanisation going back sixty years. The situation was instigated by the racist policies introduced during Belgium colonial rule; capitalised upon by French President Mitterrand, in order to maintain France’s hold on francophone parts of the African continent; and ignored by international institutions set up after World War II in order to prevent a repeat of the Holocaust. Never again.

Looking for evidence that justice had been served, I read countless commission reports. What struck me most was how the accounts differed. ‘Spontaneous tribal outburst’, ‘ethnic cleansing’, ‘complicity to commit genocide’, ‘mutual genocides’. Language – whether English or French – clearly framed different perspectives, illustrating narratives of self-justification. The more I read about the responsibility of the West, of the President of Rwanda himself, of the inaction of the institutions which had been created to protect, the more I realised I might never find satisfactory answers. Language failed Rwanda.

Looking for lessons from the Holocaust, I came across Marita Grimwood, who studied the importance of capturing the ongoing trauma of subsequent generations, and of those indirectly affected. She showed that the use of different literary forms by those writers with no direct experience of the Holocaust, provided opportunities to explore the Holocaust’s “ongoing effects in the present”. The collective Rwanda: Pour Un Dialogue Des Mémoires is such an attempt, offering a kaleidoscopic view from a group of students, historians, psychiatrists and artists who visited Rwanda’s mass graves, survivors and memorials. A second-hand account told by diverse voices. Testimonies, poems, narration, historical account, psychological analysis. Powerful. Shocking. It is telling that the collective was the brainchild of a group of Jewish students who maybe felt a moral entitlement to frame Rwanda in the continuation of the Holocaust.

The Rwandan genocide is different from the Holocaust, however. Victims and perpetrators live alongside one another, encouraged to forgive through Gacaca – community tribunals. The truth is raw, shameful, divisive. The focus has been placed on re-unifying a people rather than nurturing a shared (traumatic) memory. It occurred to me that whereas there is an extensive cannon of ‘Holocaust fiction’, written accounts of ‘Rwanda’ are either official documents, witness accounts or journalistic reports. Accurate versions of the truth told for the purpose of justification or to apportion blame. In her memoir, Clementine Wamariya wrote that “Rwandans believe we’re comfortable with silence. But silence accommodates hate.” Her story stands out as it carries an element of catharsis absent from other texts.

This made me question the role fiction could play in giving a voice to silence. Victoria is lost. My father is dead. Silence is all that is left. In The Shapeless Unease, Samantha Harvey writes that “To write fiction, you have to engage in organised fraud – the laundering of experience into the offshore of word.” However flawed the attempt, I believe that engage we must. Like Toni Morrison in Mouth Full of Blood, “[I] gather from those who have studied the history of genocide [that] there seems to be a pattern.” Repetition hides in silence.

The story that remains to be told is hidden between the gaps of memory, the omissions in the reports and the not-knowing what became of a single teenage girl with whom I exchanged letters for a few months almost two and a half decades ago. There is a risk I could be accused of cultural appropriation. To be clear, I do not pretend to know what happened in Rwanda. This story, my story, is that of two teenage girls, and the gap left by their interrupted correspondence. The result is an imperfect, partial account, combining memoir, documentary and fiction. Not knowing what became of Victoria, I fictionalised what happened to her either side of those letters we exchanged. Keen to break the silence, I lent Victoria my voice.

You might also like…

Gemma Pearson reviews the debut novel from Alexandra Ford, What Remains at the End.

Sophie Buchaillard is Associate Member of the Society of Authors. She is currently working on two debut novels, Victoria and Little White Lies, whilst completing her MA in Creative Writing at Cardiff University. She is a member of the Welsh Writers’ Group A Zoom of Our Own. Sophie also facilitates workshops designed to support aspiring and established writers alike.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.