Sean Tyrone’s son sets out from Ireland on a mission to find his father: his destination Aberuffern in the Welsh valleys, the last place his father was heard from. Reading the first few pages, I wonder if this is a heart-warming family reunion story. Further from the truth I could not be.

The book, as suggested by the title, is horrific. Or, rather, hellish. Aberuffern, in fact, is hell itself, and chapter after chapter exudes a convincing and undeniably frightening picture of what hell might be like.

For a novel concerned with such horrors as a character who murders his girlfriend’s father by hanging (with his trousers down so that people would think it was a twisted fantasy gone wrong), you would assume the writer was going for grim ultra-realism, commenting on the nature of psychopathy and the twisted mind and motives of those who would take human life. You would think, given the similarity of some of these horrors to recent news stories about murders this year in the UK, in Wales even, that it was a social commentary, perhaps an exploration of the mind of a murderer. But, aside from a few rare moments of stark realism, Sean Tyrone reads like a fairytale or folk story, characters’ actions and events deliberately questioned by the narrator from the first page. There is something altogether different going on here.

by Mark Ryan

Our narrator is Jack O’Brien, the son of Sean Tyrone. He seems to be everything his father is not: naïve, trusting, innocent, lacking in every sort of self-confidence and worldly wisdom. And he admits on the first page that the whole story might be an exaggeration, or perhaps a trick of his memory. What is clear from the chapters that follow is that Sean Tyrone, in stark contrast to his son, is a devil, and that this, far from being a simple ‘find-my-father’ tale, is a complex, multi-layered book which is, through its various narratives and formulaic repetitions of scene and character, speaking quite clearly of humanity, if not 21st century Welsh society.

The traditional ‘atmosphere’ of hell is absent. There are no torturous flames, no grinding teeth, no screams of torment. The hellishness is caused wholly by characters’ actions, by the violence, corruption, deception and cruelty of Sean Tyrone himself and the band of three ‘demons’ Jack meets along the way: Dave, Mary and James (later Dafydd, Mair and Jams; then Dewi, Maria and Jimmy). The trio exploit Jack’s innocence, abuse him, mock him and so demonstrate his lack of worldly knowledge that Jack is increasingly seen as the counter to his father, the wife-beating, murderous old devil himself.

There are, interjected between Jack’s chapters, accounts of how Dave, Mary and James died. They read like sad short stories, epitaphs of waste and misery, and they jar against the main narrative.

Continual references to life being like a game of cards leave me none the wiser as to which hand has been played, or to who is winning.

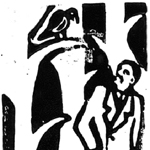

There are other strange interjections also: each chapter begins with a poem, or song, and there is song throughout the pages, adding a sense of grandeur to the narrative (one is called ‘The Ballad of Sean Tyrone’). And these are often more effectively rendered than the prose: Ryan’s background as a songwriter and playwright is clear here. The woodcut engraved illustrations which accompany the text, the author’s own handiwork, are testament to his clear creative skill and the breadth of his abilities, and they hover over the text, the black and white block silhouettes evoking in image the terrifying world Ryan paints in his prose. They would make a beautiful exhibition on their own.

But it is the lack of a moral compass which perplexes most, disturbs. Continual references to life being like a game of cards leave me none the wiser as to which hand has been played, or to who is winning.

But perhaps it is not a game at all: perhaps the trick that Dave, Mary and James play on Jack is indicative of the wider trick life plays on us, their stark mantra ‘you play, you pay’ a key to Ryan’s dystopian view of our twisted society. Hell itself. As the book draws to a close, you certainly get the feeling that Ryan is playing tricks on the reader.

I can see how this would have worked as a piece of theatre (the book is a novelisation of a play performed in Chapter Arts Centre in 2010). I can imagine how the audience would feel leaving the theatre having had their world turned upside down.

There are so many layers to peel here, and I feel I’ve only just shifted the skin.

It’s certainly not an easy read. And a Symphony of Horrors is, perhaps, a slightly disingenuous title; though the horrors are clear almost from the first page, the idea of a symphony casts too beautiful a picture for this book. Unless of course the orchestra’s out of tune, the violinists scraping discordant violin strokes as the Requiem reaches its frightening conclusion.

Thinking again, that fits the picture of hell quite… nicely.