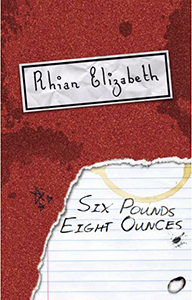

Seren Books, £8.99

The first thing you should know about Rhian Elizabeth’s debut novel Six Pounds Eight Ounces is that Hannah King – the protagonist – is a liar. Hannah also tells us that we should not ‘believe a single word in my notebook about my crazy friends and my crazy family.’

The first thing you should know about Rhian Elizabeth’s debut novel Six Pounds Eight Ounces is that Hannah King – the protagonist – is a liar. Hannah also tells us that we should not ‘believe a single word in my notebook about my crazy friends and my crazy family.’

With this in mind, as you turn to the opening page you wonder if the awaiting story is going to be the thoughts and imagination of a too-overworked-brain or a true rendition of an actually crazy life surrounded by crazy people and even crazier events that have been further fabricated by the, frankly, excellent back-cover blurb. From an intrigued perspective, the latter hopefully is the case although we never find out if anything we have just read in the 292-page novel is true. Is this frustrating? No. The writing itself is so silky, absorbing and brilliant that you’ll forgive Elizabeth for imitating her protagonist and refusing to tell us The Truth. The last sentence – which I won’t give away for those of you who have not read the novel yet – does more than just add mystery to the series of events we have taken part in on Hannah’s journey; it manages to bring us back to reality after being sucked into the comedic, soul-jerking, sad, roguish story Hannah tells us about. It also spits spitefully from the page – leaving you a bit cheated. But, again, you can forgive Rhian Elizabeth because that sentence represents Hannah’s character to a tee.

The novel is the story of Hannah and we travel through her life with her – from primary to comprehensive school to running away from home to sexual first encounters, to drug use, to the death of a person Hannah and her best friend, Jessica, somehow manage to shack up with. Of course, these are only the stand-out plot points. Sprinkled in between these are other events, which manage to fully document Hannah’s personality and life to such an extent that you feel yourself standing next to her as she’s walking to school, watching her as she scribbles in her notebook and standing sheepishly as she argues (again) with her mother. The novel effortlessly moves through Hannah growing up, through conversations, events and character progression.

Every aspect of this novel addresses the reader front on, as if Hannah is sat next to you and chatting away. An example of this is on page twelve: ‘I’m ginger, poor dab, Nanny says, and I’ve got freckles all over my face. This means I can’t be on the telly, or famous or pretty or anything, but I’m okay with it.’ The sentence is realistic, funny yet laced with melancholy. Much like the rest of the novel.

As well as being a gritty novel about a young girl’s life in the Rhondda, there are also glimpses of Rhian Elizabeth’s poetic hand that flash and flare amongst the words. These descriptions act as breathing space, service stations, for the reader when the novel might be becoming too heavy and laden-down by Hannah’s angsty and – often – unfortunate life. For example, on page nineteen you’ll find the dazzling: ‘Hers fly gracefully from her mouth like doves but out of mine crows come screaming’, and on page forty-five you’ll find a personal favourite: ‘…the crash of coins into collecting trays is as loud as a hundred knives and forks falling out of the sky.’

The strongest chapter is ‘Danville’. It leaves you with a lump in your throat through the immediate introduction of Hannah’s dad, who we only manage to snatch snippets of before the chapter. The introduction of her dad is very effective, like he has been waiting behind curtains the whole time to surprise us all. It is a lovely, picturesque, autumnal, sepia-like chapter of a long-lost father and his daughter re-united. Once we are told about Hannah and her dad, and how they engage with each other, we cannot wait until he swoops into the novel again and leave a bittersweet taste on our fingertips.

There are cultural references scattered around the novel, too. References that only people who grew up in the Rhondda – or have spent a lot of time there – will truly understand the significance of. Ponty Park, Trealaw Cemetery and the Taff Trail are the main references alongside smaller ones such as Tonypandy Comprehensive. As I grew up in the Rhondda, reading about these places left me feeling nostalgic and even a bit homesick – thinking about my own childhood and the places where I spent it. It also made my mind wander as to how those friends I spent my childhood with are doing now.

One aspect of the novel that haunts the pages is Hannah’s relationship with her mother. Hannah thinks her mother doesn’t love her and that she is a hindrance; every teenager has had those thoughts but reading those thoughts from Hannah’s perspective, as an adult, you appreciate that your mother did indeed love you and always will. The lies Hannah tells her mother and the whole treatment of her mam sort of makes you feel a bit sorry for Mrs King but then you realise that you shouldn’t feel sorry for her at all. It is Hannah you should be feeling sorry for. And she is only too happy to tell you. The mother/daughter relationship is another relatable characteristic of the novel, one that runs deep – from the very beginning – and you are transfixed to the pages waiting for something, anything, to push their relationship further to the brink and when it happens there is a lethal concoction of regret, triumph and melancholy racing through your veins.

Will we ever find out what really was in Hannah’s notebook? Hopefully, yes, because this novel points in all the right directions and signifies Rhian Elizabeth as a sure literary star in the making.