On February 6th, 1918 the first women and all men in Britain gained the right to vote. Cerith Mathias was in Westminster for the 100th anniversary.

The Representation of the People Act turned 100 last week, marking a centenary since the law which enabled some women – those aged over 30 in possession of property, or who were the wives of property owners, the right to vote. The passing of the Act was symbolically huge, the culmination of years of suffrage campaigning – both peaceful and militant. Although it would be another decade before full voting equality was realised, it was a momentous first step on the long and ongoing journey in the fight for women’s rights.

This year a series of milestones in the fight for democratic equality are being celebrated, with last Tuesday’s anniversary kicking off events throughout the UK, many under the banner of Parliament’s Vote 100 programme, which is organising talks, tours and a major exhibition in the oldest building in the Parliamentary estate, Westminster Hall.

It’s there that a not insignificant crowd, of which I’m part, has gathered on a cold Tuesday night in February to honour the courage, determination and sacrifice of those women and men who fought to bring about change. The hall is packed: politicians bedecked in suffragette rosettes, women’s rights campaigners, relatives of both prominent and lesser known suffragettes, and the media fill the vast space with excited chatter. A choir at the far end of the hall sing suffrage marching songs. Actors posing as famous faces from the movement weave through the crowd in Victorian and Edwardian dress.

The mood is genuinely jubilant – earlier that day Labour MP and prominent feminist Jess Phillips took to Twitter to declare ‘Today feels a bit like feminist Christmas in the House of Commons.’

As well as the sea of purple, white and green – the battle colours of the suffragettes, many are sporting red, green and white sashes and ribbons – the colours adopted by the lesser known suffragists, who had been peacefully, yet persistently campaigning for the vote since the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) had been established by Millicent Fawcett in 1897. Fawcett believed in legal means as a form of effecting change, employing tactics such as non-violent demonstrations and petitions and the lobbying of MPs. Although moderately successful in winning the support of some MPs, more militant members of the cause were growing impatient. In 1903, Emmeline Pankhurst formed a breakaway group – the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), whose more extreme, confrontational activities – window smashing, burning post-boxes and hunger strikes, led the Daily Mail to dub them suffragettes.

‘Miss Wilding Davison, I must most strongly disagree,’ says a voice behind me.

I turn to see Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, sister of Millicent Fawcett and the first female doctor in Britain standing with Emily Wilding Davison, perhaps the most well-known suffragette of all; or rather, the women as portrayed by Rosanna Summers and Kate Howard from the historical interpretation group Past Pleasures.

Garrett Anderson continues. ‘Violence, my dear, will not endear many to our cause.’

I lean in, keen to listen to both suffragist and suffragette debate the merits and pitfalls of both approaches.

‘With respect, Mrs Garrett Anderson,’ Emily Wilding Davison retorts, the long black feather on her hat quivering as she raises her voice.

‘Now is the time to act. Deeds not words, Mrs Garrett Anderson. Deeds not words!’

Looking around the small group of curious onlookers that has gathered around us, Emily opens her purse to reveal her suffragette sash.

‘I’m not meant to be here,’ she whispers conspiratorially ‘I’m going to find somewhere to conceal myself, but please don’t say you’ve seen me.’

A reference to the night of the 1911 Census, when, to have her address recorded as the Houses of Parliament, the real-life Emily Wilding Davison concealed herself in the broom-cupboard of the chapel underneath the spot where we’re now standing. Just up the stairs is St Stephens Hall, where the statue of Viscount Falkland stands, damaged by the chains suffragette Margery Humes used to secure herself to it.

‘I’m thinking of something bigger,’ Emily is saying. ‘Perhaps draping a sash around the neck of the King’s horse.’

As the actors move on to the next group, I wonder what both Elizabeth Garrett Anderson and Emily Wilding Davison would make of the fact that we are this evening in the company of so many female politicians and that in a moment, the room will fall silent as a female Prime Minister pays her respects to them both and to all the other ‘soldiers in petticoats.’

‘Because the right to vote was not handed over willingly,’ Theresa May, only the second ever woman to become British Prime Minister will say. ‘Rather it had to be forced, over many years of struggle from the hands of those who held it for themselves. All around us here are reminders of what that struggle looked like.’

According to official records, the Representation of the People Act was passed in Parliament by Royal Assent at precisely 8pm on February 6th, 1918. As I watch female MPs past and present gather for a photo at the far end of Westminster Hall, I glance at the clock on my phone screen, which tells me it is exactly 100 years since that moment took place here.

********

Many other important moments in the struggle for political equality are being noted this year, among them the centenary of women being able to stand for Parliament, and the 60th anniversary of the Life Peerages Act.

‘It was actually within my lifetime that women were first allowed to sit in the House of Lords. That happened in 1958, so these changes are remarkably recent.’ Baroness Jenny Randerson tells me. The former Cardiff Councillor and Welsh Assembly Member is now a Liberal Democrat Peer and has held ministerial positions in both the Welsh and UK governments during a political career spanning over 30 years. We meet in the House of Lords, of which Randerson has been a member since 2011. It is an impressive, if perhaps intimidating building, and walking the red carpeted, book lined corridors towards the tea room, I think of the impression it must have made on Baroness Swanborough, the first woman to be introduced to the Lords.

‘I was at a meeting earlier on this afternoon in a room with a picture of the House of Lords in 1962,’ Jenny Randerson says as we pass painting after painting depicting men from history. ‘It was a picture of the whole chamber. And I noticed, there were only two women there.’

Though the artistic representation of women in the Lords may be found wanting, there is however one painting here that is particularly significant to Randerson – that of Lady Rhondda. A leading feminist, journalist and businesswoman who ran the Newport branch of the suffragettes, Margaret Haig Mackworth, daughter of the 1st Viscount Rhondda, was known for her activism. She attempted to blow up a post-box on Risca Road in Newport with a home-made bomb and was sent to Usk prison in 1913 for refusing to pay a fine relating to the attack. When she inherited her title from her father, she began campaigning for the right to take her place in the Lords. She died in July 1958, three months shy of being able to take her seat. In 2011 a portrait of Lady Rhondda finally went on display in the Lords dining room.

‘Before me here, from the Liberals in Wales, there was only Lady Rhondda,’ Randerson says. ‘Now there’s also Christine Humphries. We are the only Liberal women who have ever been in the House of Lords from Wales. When you think of it in those terms, we’re only at the beginning.’

Finding herself on the ground level of political change isn’t something new for Jenny Randerson. As a councillor in Wales’ capital city who, despite being in her thirties was referred to as ‘my girl’ in the chamber, she went on to be part of the first intake to the National Assembly for Wales, which in 2003 made global headlines for becoming the first legislature in the world to achieve a 50/50 gender balance. This, she says was not only vital for women’s political equality, but for the people of Wales as a whole.

‘You could feel the difference, you could hear the difference. Women see things that men don’t see, and I’m sure men see things that women don’t see. I think it’s important you’ve got both looking at a problem,’ she says. ‘The Assembly really made me appreciate that women bring a different perspective to policy making; it’s a very important perspective. Lots of women can change things.’

As we sip our tea, seated in the burgundy and gold décor of a room overlooking a grey, choppy river Thames, Randerson talks of the importance of visible female role models in public life. She mentions her grand-daughters, who she says are being raised as feminists by their mother, her daughter-in-law.

‘Part of their feminism is that they come here (to the House of Lords) and they learn that grandma doesn’t just bake a decent cake, there’s more to her than that. This is what grandma does during the day when she’s not looking after you.’

But for those without such an immediate point of reference, Randerson says an increase is needed not only in female politicians, but in female politicians with power.

‘It’s not odd that our Prime Minister is female, it’s not odd that our Home Secretary is female. I think it being the norm is so important.’

As a former Culture Minister in the National Assembly for Wales, she finds another form of visibility is also key to progressing women’s rights and bolstering the ambitions of young girls. Public art made by and about women helps to bring their stories to the fore. As attested to time and time again by feminists today – you can’t be what you can’t see.

Banners and posters from the suffrage movement currently feature prominently in museum displays throughout the UK celebrating the centenary of women’s voting rights.

‘When you see something like a banner, that’s so beautifully stitched, you say, well let’s think about this,’ Randerson says. ‘The woman who did this probably had half a dozen children, may well not have had electricity in her home, so she could only do this during the day. She had to cook, and clean and she stitched all of this beautifully by hand, and she still had time to worry about her political rights. It’s remarkable.’

This idea of craftivism – activism through arts and crafts – was a central tenet of the suffrage campaign and is one that continues to be employed by women’s groups to this day. At the height of the suffrage movement, the Women’s Social and Political Union opened Women’s Press Shops, which sold suffragette literature and other items, as recorded in the Votes for Women newspaper in 1910:

‘The shop is itself a blaze of white, purple and green…Indeed almost anything that can be produced in purple, white or green or a combination of all these is to be found here.’

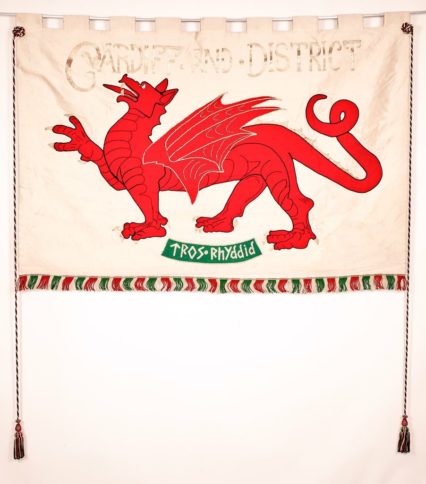

Marches and rallies, organised by both suffragists and suffragettes became known for their beautiful, handstitched banners – bold in both design and in message. Indeed, the banner of the Cardiff and District Women’s Suffrage Society, the largest branch of Millicent Fawcett’s National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies outside of London, reportedly caused quite a stir.

When I see it, it is on display in St Fagans National Museum of History near Cardiff. Designed and sewn in 1911 by the President of the group, Rose Mabel Lewis of Tongwynlais, the banner’s colours remain strikingly vibrant. A blood red Welsh dragon takes up much of the cloth, and the words ‘Tros Rhyddid’, meaning ‘For Freedom’ are stitched underneath, along with a row of alternating red, white and green.

‘There’s a hidden language to this banner,’ Elen Phillips, the museum’s Principal Curator of Contemporary & Community History tells me.

‘It’s very identifiably Welsh with the green, the white and the red, but green, white and red were also the colours of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies. The purple, the green and the white were the more militant branch of the women’s suffrage movement. So, the colours are significant in both contexts.’

The banner was paraded on the streets of London during both the coronation procession of 1911 and the great suffrage pilgrimage in 1913. It was during the former that it attracted quite a bit of attention.

‘There were about 40 to 50 thousand women and men marching in London on June 17th, 1911 for the coronation.’ Phillips says. ‘Apparently when one group of onlookers saw the dragon, they shouted “Here comes the devil!”’

The banner, along with another belonging to the Cardiff and District Society, currently housed in Cardiff University, will make their way to the Senedd later in March to form part of a display on Wales’ contribution to the suffrage cause, and banner making sessions are to be held in St Fagans museum.

New public art is also being created to celebrate the contributions of suffrage campaigners. Government backing has been given to a statue of Emmeline Pankhurst in her native Manchester, while in Wales, the Leader of the House in the Assembly, Labour AM Julie James announced last week that two statues of inspirational Welsh women will be commissioned following a public vote in the autumn. Back in London, a woman will take up residency in Parliament Square for the first time when a statue of Millicent Fawcett is unveiled in April, the names of 59 prominent figures from the suffrage movement etched on its plinth.

London Mayor, and self-declared proud feminist Sadiq Khan unveiled the names and portraits of those to feature on artist Gillian Wearing’s statue in a pop-up exhibit in Trafalgar Square last week. Placed at the foot of Nelson’s column, the life-sized black and white pictures attracted crowds throughout the day.

‘It’s really exciting,’ Lucy Anderson, a student from Sheffield says when I ask her why she’s come to the exhibit. ‘It feels like people are actually starting to take notice of what women have to say, I feel like things are going to change.’

‘These women were so brave,’ Pam Shephard, from London says waving her arm animatedly towards the cardboard gathering. ‘It’s about time there was a statue of a woman. The only ones I can think of are of men.’

Among those included in the display, and eventually named on the statue, are Lady Rhondda and Edith Mansell- Moullin, the founder of the Cymric Suffrage Union and organiser of the Welsh contingent in the coronation suffrage procession of 1911. She is pictured looking proudly and directly at the camera, in full Welsh costume. Also present is the well-known Liverpudlian women’s rights campaigner and social reformer Eleanor Rathbone, whose great-great niece Jenny Rathbone has been a Labour Assembly Member for Cardiff Central since 2011.

‘I’m very proud to see her there, it’s quite right that she is,’ Jenny Rathbone says when I speak to her on the phone. ‘She succeeded Millicent Fawcett as President of the Suffrage Society and went on the become a very effective MP.’

Liverpool’s proximity to North Wales meant that Eleanor Rathbone was also involved in helping the Welsh campaigners.

‘It’s important we record the women, particularly those from North Wales who walked to London in 1913,’ says Jenny Rathbone. ‘Eleanor was of course involved with that, with the organising. In Wales we’re looking to honour 100 prominent campaigners for women’s suffrage here.’

While honouring those who took up the struggle for women’s rights is thankfully the order of the day in 2018, a hundred years ago attitudes weren’t always as positive. Posters from the first decade of the twentieth century on show in the Museum of London liken women seeking the vote to ‘convicts and lunatics.’ A print of a newspaper front page says clearly in bold capital letters ‘LET THEM STARVE. THE VIEWS OF PUBLIC MEN.’

In the National Museum of History in St Fagans, two dolls form part of its women’s suffrage collection. Both effigies depict female suffrage campaigners as having hard, masculine features. One is named ‘Flora Copper’, a pun, suggesting an attack on a policeman – to floor a copper. The second is far more sinister, having an almost voodoo doll like appearance. According to curator Elen Phillips, de-coding the message of both items isn’t difficult.

‘These anti-suffrage dolls have hatred in every stitch,’ she says. ‘A large part of the anti-suffrage propaganda was that women who were campaigning for the vote were un-feminine, they’d be poor mothers, the household would disintegrate around them. They’re typical of the negative stereotype.’

It’s not a vast leap to draw contemporary comparisons between the dolls and the treatment of women today.

‘We’ve had people compare this doll to online trolling,’ Elen Phillips muses. ‘It’s like a nasty Tweet, or the hate mail that women in public office receive today.’

Indeed, the first anniversary of the global women’s march has just passed, with the #MeToo and Time’s Up campaigns against harassment gaining momentum the world over. It’s worth noting too that in the week that marked the centenary of the first women getting the vote, recommendations were published by a cross-party group of MPs for a new code of behaviour in parliament after widespread accusations of bullying and sexual harassment.

We’re 100 years on from those first steps towards democratic equality – but just how far has the fight for women’s rights come? For Baroness Randerson, not far enough.

‘There hasn’t been the fundamental revolution that I would have wanted. Of course it’s changed but one of the disturbing things is, it hasn’t changed that much.’

Is she hopeful for the future, I ask, as despite the struggles of the women who have gone before, worryingly 36% of eligible female voters failed to vote in the 2015 general election.

‘I get worried that some women don’t value the precious gift they’ve got. That they take it for granted. That’s why this anniversary is so important,’ Randerson says. ‘I look at the younger generation, and they’re not going to put up with it. They’re being bred differently. The world you grew up is different to the world I grew up in, but it’s not as feisty as the world of girls now. That gives me hope, but we still have a lot of work to do.’

Leaving the House of Lords in the fading afternoon light, I head to the adjacent Victoria Tower Gardens, a triangular patch of green that hugs the Thames from Lambeth Bridge to the famous Palace of Westminster Tower, albeit the one without the clock, which is currently clothed in a straight-jacket of scaffolding.

At the very edge of the gardens, a stone’s throw from the Lords a statue of Emmeline Pankhurst is tucked away just out of sight from the road. A memorial to both the suffragette leader and her daughter Christabel, it was unveiled in 1930 by the then Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin, who himself had opposed granting the vote to women. Inside the statue’s pedestal is a metal box with a selection of Mrs Pankhurst’s letters and her obituary from The Times.

As I pass, I notice that someone has placed a bouquet of flowers at her feet, blooms of purple and white intertwined with lush green foliage, tied with ribbons of the same colours. A white card is propped up against the flowers, words to celebrate deeds. It reads, simply: ‘To those who led the way.’