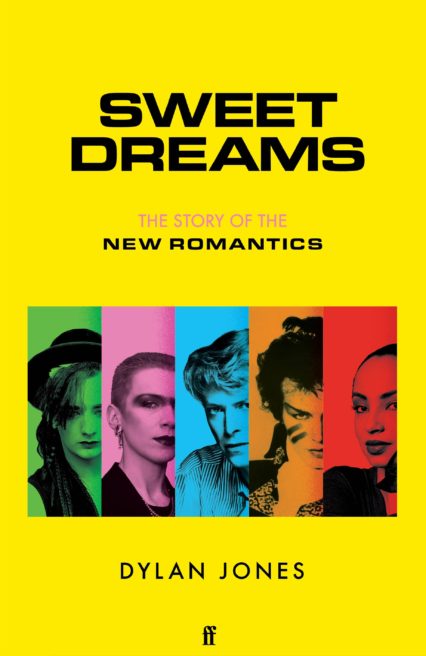

In advance of the publication of his much anticipated book Sweet Dreams: From Club Culture to Style Culture, the Story of the New Romantics, GQ Editor, and original Blitz kid, Dylan Jones spoke with Craig Austin about Blitz, Bowie, the 1980 style wars, and the pivotal influence of Soho’s Welsh contingent.

In late 1980 Spandau Ballet introduced themselves to the general public with a swaggering Top of the Pops appearance promoting To Cut a Long Story Short. An inspirational and futuristic debut single whose self-referential declaration ‘I am beautiful and clean and so very, very young’ was as calculatingly confrontational as Sex Pistols’ Anarchy In the UK had been only a few years prior.

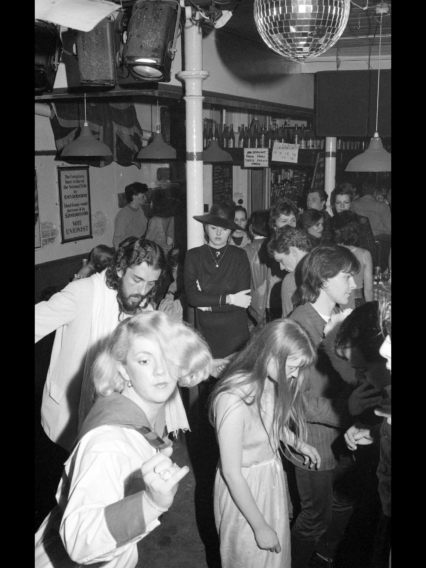

A collection of feisty working-class kids from Islington, they had first emerged as the anointed house-band from Blitz, the celebrated Covent Garden nightclub that spawned the globally influential New Romantic movement and ultimately set the New Pop template for the first half of the 1980s. An explosion of creativity that saw the likes of Spandau, Duran Duran and Culture Club emerge from the shadows of the nightclub into the bright lights of MTV. ‘One thing we were utterly sure about’ recalls broadcaster and soul stylist Robert Elms, ‘was that we were going to make something that was an evolution of what had come before, taking the baton from punk, spitting in its face at the same time and going to the next step’.

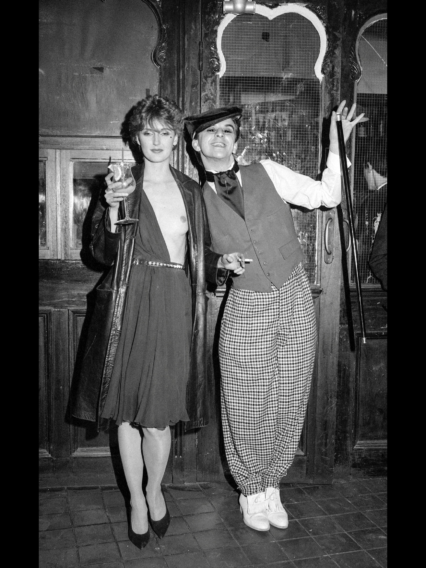

In his latest book Sweet Dreams GQ Editor Dylan Jones charts the flamboyant rise of the New Romantic movement via the extensive and vivid recollections of its principle participants. As a survivor of the 80s style wars, and as a witness to the Soho club culture that set the style agenda for the decade, Dylan Jones is ideally placed to chronicle a scene that first grew out of the remnants of post-punk but which quickly saw its burgeoning influence splashed across the covers of the tabloid press in a cavalcade of breeches, frilly shirts, white stockings and ballet pumps.

One of the most creative entrepreneurial periods since the Sixties, the era had a huge influence on the growth of print and broadcast media, and arguably represented one of the most bohemian environments of the late twentieth century, an artistic influence that resonates to this day. An entire generation of writers, artist and musicians took their primary inspiration from a weekly Tuesday club night in a faded wine bar in the central London hinterland. Its flamboyance, arrogance and unique sense of purpose and destiny created as many enemies as it did converts, but despite the retrospective derision that’s since been thrown its way its hard to argue that its impact upon the look and aspirations of a generation was anything short of transformative.

‘There have been hundreds of book about punk, heavy metal, soul, all forms of dance music’ the author tells me, ‘but this is a much maligned period, one that’s been treated badly by pop historians in the narrative arc of post-war pop culture. I wanted to reclaim that. Not only is that period responsible for some of the greatest pop music in terms of singles, it’s probably comes second only to the years ‘64-’68 when it comes to the global influence of British music. It was a period of bohemianism, of great freedom, and an important period for gay emancipation. It’s easy and lazy to view the 80s as simply being shrill, a time of style over content, of surface over substance, and in my very small way I want to say that that isn’t true’.

Dylan Jones charts this fascinating story via a 10-year narrative that commences in the pre-punk post-glam Britain of 1975 and ends, conclusively so, in Wembley Stadium in July 1985 with the heritage rock extravaganza of Live Aid. As an oral history of the period it already feels like the definitive statement on the time with around 80% of the material being drawn from contemporary interviews conducted by the author; himself the former editor of i-D magazine, one of the most persuasive voices of the 80s style press.

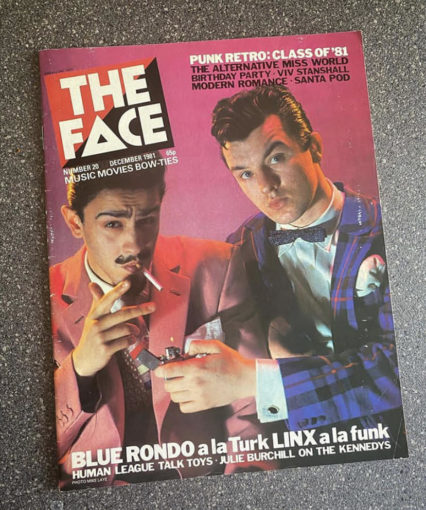

‘Those magazines were incredibly influential’ he reflects. ‘i-D, The Face and Blitz all launched within months of each others, and like the good magazines of any period they not only reflected the culture, they were part of it. There was a sense of arrogance about it, yes, but it was arrogance shared by a group of people who decided, “we’re going to create something and it’s going to happen. If we say black is white there are people out there who’ll say, “well maybe black is white…” You were very much contributing to the culture in a serious way as well as in a frivolous way. It’s why I believe those magazine remain very important in specific and different ways’

The sense of speed and of change is palpable within the pages of the book: ‘You knew things were happening and you knew that interesting things and people were coming out of this world, but it took a while for that to manifest itself in terms of music, and the music itself came from a variety of different places. You had a number of synth duos who had been very much inspired by Kraftwerk, the multitude of people who took inspiration from Bowie and Roxy, the likes of Spandau and Boy George. And you also had the old punks who were suddenly dressing themselves up in fancy dress, people like Adam Ant. A lot of these weird rivulets were moving about all at the same time’

And so, inevitably, to the overriding cultural influence of Bowie and Roxy Music upon the scene; the artists that first lit the flame of creativity and possibility in the next generation of pop kids. The initial run of club nights at Billy’s (the Soho precursor to Blitz) was known as ‘Bowie nights’ and promoted by flyers that declared ‘Fame, Fame, Jump Aboard the Night Train’, while Bryan Ferry remained, even in the late 1970s, the aspirational clothes horse to many of the scene’s movers and shakers. Dylan Jones references both men within the key strands of the story before seemingly coming down on the side of Roxy as the primary influence of the age, citing the band’s Mother of Pearl as its definitive text:

‘In terms of inspiration Ferry was certainly as influential as Bowie. Bowie was a more interesting artist but in terms of kick-starting this particular generation of youth culture Ferry was hugely significant. It was an influence that had its limits though. When you’re in your teens the level of sophistication that Ferry aspired to was so far out of reach that it appeared to be insanely glamorous, and also correct, that there was nothing wrong with it. The more sophisticated that people became though the more they came to see that his take on it was a bit ersatz, a bit fake. He proved to be a truly enduring artist though and he was right there in kick-starting an interest in something other than the accepted norms in the early to mid-70s’

‘Bowie and Ferry inspired ambition in people, but these people were mainly ambitious in their desire to further their craft. It was a kind of arrogance but I don’t believe it displayed itself as that. There was some kind of inner momentum that felt collective and I think it felt collective because if you’re involved in any scene, regardless of how important it turns out to be, you always feel it’s extremely important, whatever age you’re living in. I certainly experienced a heightened sense of awareness about what was happening though, there really was that. It started to feel that things were expanding beyond the Soho nightlife scene quite rapidly. You’d see a picture of someone you knew in a magazine and think, Jesus Christ! Then you’d see and ad for someone you knew who’d made a record and think, Jesus Christ! Then you’d see someone else on Top of the Pops, and again, Jesus Christ! People you actually knew had suddenly leaped into a mediated world, from the previously small world of a nightlife scene, the goldfish bowl in which we existed. But that goldfish bowl was responsible for the second British Invasion, a brief period that in 1983 saw three-quarters of the American Top 40 being made up of British acts, something that only ended with Live Aid’.

What’s often been lost in the story of this period is the hugely influential roles played by its Welsh contingent; by Steve Strange, London’s most intimidating doorman turned visionary pop star, by Chris Sullivan, the Merthyr dandy whose love of Latin music manifested itself in the success of a club scene that emanated from Le Beat Route and in the output of his own band Blue Rondo à la Turk, and by Cerith Wyn Evans, the conceptual artist who won the Hepworth Prize for Sculpture in 2018.

Strange, from Newbridge, who originally connected with scene DJ Rusty Egan at a Rich Kids show in Newport, was almost uniquely adept at ‘making things happen’ and swiftly ingratiated himself with the old guard of London nightlife, the likes of Peter York and fellow Welsh firecracker Molly Parkin. There evidently came a point where his originality and speed of thought began to break through, the point within the story at which Spandau manager Steve Dagger began to think, ‘You know what? Maybe this guy can really sing, maybe he could do something. Maybe he isn’t just a twat from Wales’. Sullivan meanwhile made a name for himself within London before he’d even upped sticks and moved there, taking an unspeakably early National Express coach from Merthyr every Saturday morning to ensure that he was parading down the Kings Road by noon. Dylan Jones recognises this ingenuity and is quick to laud it:

‘If you’re from the suburbs, or the provinces, or any of those other patronising terms for things that aren’t in London, it’s easy for people to think less of you. But in the same way that those magazines were essential, those people also weren’t just participants in the culture, they became part of it and helped to define it. Those three people were fundamental to the scene, take them away and it becomes much diminished. Steve and Chris were part of the DNA of club culture at the time and Cerith became one of our most important artists. Cerith would have been successful anyway, but Chris and Steve, they created something. If you look at modern music culture it’s predominantly driven by dance. Mainstream pop is dance music, rock music’s been on the wane for some time. You can draw all of those lines through to the 1978/79 in The Blitz and Billy’s. To a small nucleus of people whose influence would lead, in 40 years time, to a world in which people would consume almost all of their music by BPM. They may not be walking around in ecclesiastical garb covered in yellow make up, but you can certainly trace modern music back to those club nights’

‘I was young and at first I’d often attend the clubs on my own’ Dylan Jones reflects. ‘A couple of years prior to that punk felt very new and offered me the excitement I was looking for. It was a violent and quite intimidating period in London and that’s not often mentioned, it could be very frightening. I’d often be on speed, which makes you anxious enough anyway, and this combined with the violent atmosphere of the gigs made for quite a threatening night out. Two or three years later, when the Blitz scene came along, I found myself surrounded by an increasingly flamboyant and glamorous group of people, a lot of whom later became my fiends. The intimidation was still there but it was a different kind of intimidation. In the early days it was a madhouse, and I often compare it to the bar in Star Wars, as there were a lot of very big characters in the room. It wasn’t always easy to get to know people at first as you first had to get past their armoury. It was a little like a battle, and dressing up was your battle dress, as was your warpaint. You’d dress up to attract people, then slowly reveal parts of your character, to show people what you were really like’

When speaking with the author, Spandau Ballet’s Gary Kemp is refreshingly unapologetic about the innate sense of elitism that permeated the early days of the scene: ‘I think that was part of what we were trying to sell. That’s what pop music tries to sell to you; it’s what youth culture tries to sell to you. It tries to sell something unique: a club that’s very difficult to get into. Once everyone is in, like punk, you don’t want to be there anymore, you want to go somewhere else. When we look back at our idols, like Bowie and Ferry it was their aloofness that first attracted us’

A timeless inspirational narrative that ultimately re-imagined the future for an entire generation and which set out to take on the world with little more than the bullet-proof swagger of creating ‘the most contemporary statement in fashion and music’. At the crossroads of the 70s and 80s, sweet dreams were made of this.

Sweet Dreams Sweet Dreams

Sweet Dreams: From Club Culture to Style Culture, the Story of the New Romantics by Dylan Jones (Faber) is published on October 1st 2020.

Sweet Dreams Sweet Dreams