When Gwyn Thomas trained his novelist’s eye like a searchlight on the Terraces of the south Wales valleys, on the ‘voters’ of the Rhondda and their all too human ways, he was not just out to illuminate, to examine their tribulations and multifarious tests. He was also out to entertain, and there’s barely a sentence of this hyper-oxygenating novel – written in the same deep breath that brought the early gems Oscar and The Dark Philosophers into the world – that doesn’t show off Thomas’s trademark, mordant wit.

Indeed I started marking down sterling examples of that wit on a sheet of paper folded into the novel’s pages but found that I was in real danger of copying out the whole work in longhand, like Pierre Menard in that Borges story about the man studying Cervantes. So let this one example suffice for now, as Shadrach Sims, the impresario grocery owner, surveys the sad cohort of men who are putting up adverts for his shops up and down the valley:

‘I see now,’ he said. ‘Upon you all is this terrible ravaging sadness. Within some there is the steel knot of pride or obstinacy or even sheer damned daftness that refuses to be flattened by the falling sky. But others,’ he pointed at Morris, ‘others exist for the pure reason and love of being crushed. They like counting the pieces that are left over, even put them in position for the cruncher and wait for the great day when they can introduce themselves to the family as a box of the finest powder, the family’s first and only gift from the old man…’

The story of thwarted love among a desperate populace sees Gwyn Thomas don a mortician’s smock before wielding his sharpest scalpel, using the sharp edge of the most bitter satire to cut into life as lived by people who’d happily rub two pennies together if only they had that many coins.

by Gwyn Thomas

The Alone to the Alone has at its heart the rags to riches and then back to tags story of Eurona, a young girl whose beauty is hidden under the shocking tatters of her dresses. This ‘fair specimen of the woeful doctrine that spoils all dignity and negates all purpose in the community’ is given some new duds, and a new sense of purpose, after pleading with the authorities for money for new clothes. Dressed in her new finery, complete with cardboard heels, she manages to attract the man she’s been fawning over, the feckless, lothario bus conductor Rollo, who then casts her away in favour of a rich widow, leaving the broken-hearted Eurona to burn her clothes and dive into a lagoon of despair, as Thomas might have put it, and probably did put it in some novel or other. Half way through the novel switches focus, concentrating on Shadrach’s return to the valley, and on his seductions. He takes the widow away from Rollo, and then attempts to do the same with Eurona, and all the while his actions – and the actions of most of the rest of the populous cast of the book – are being determined by one of the valley philosophers who are usually satisfied by just meeting by a wall to shoot the breeze and chat about the world and its ways.

But yet, even if this novel employs a biting wit savage as a rabid Rottweiler, it’s ultimately a portrait leavened with oodles of compassion, of understanding and sympathy with the travails of others. Even if you do find yourself laughing at the characters as often as you do with them. There’s a moment in the novel when the men employed as workmen by Sims ponder the excitement they will cause when they appear to do work on the streets, causing:

a mood of reckless joy and mad celebration to run through the Terraces, bringing a light of painful brilliance into minds long adjusted to penumbra standard, driving neighbours to crowd around us and hail us as the first swallows of their greatest spring and that we begin there and then to chirp to put the matter beyond any doubt.

Thomas’s work has been described as part novel, part historical document and there’s no doubt that laughing one’s way through his work does give you a real sense and smell of what it was like to live through the treacherous poverty of the Thirties, in teeming terraces arranged along the sides of ‘riven gulches’. It also takes you into the company and gift of a writer who can pack more into a bon mot than many others can get into a suitcase.

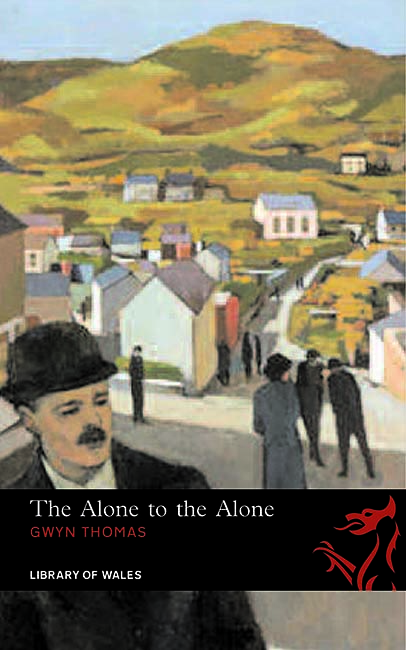

And, remember, this is still an early work. There was so much more to come. This 1947 novel may be History as Carnival, as it suggests on the cover, but what a glorious carnival, a veritable harlequinade of humanity. The carnival-goers may be drably clothed, yes, not quite the harlequins, really, but they are simply invincible in their collective dignity, in their hyperactive concern for one another, for each and every member of their harshly downtrodden and economically ravaged communities. Where they only have love to keep themselves warm.

Banner illustration by Dean Lewis