Offering a glimpse into work he discovered while visiting Kiev in 2019, David Greenslade profiles Ukrainian painter Anatoly Shmatok, writing about Shmatok’s work as a “naïve artist” and why simplicity can say so much.

I spent time in Ukraine in 2019 and have since been lucky enough to visit the neighbouring Republic of Moldova. While still living in Wales, midway between Swansea and Cardiff I also organise exhibitions in Romania, where I spend a lot of time.

One of the artists I feel particularly lucky to be working with is the Ukrainian painter Anatoly Shmatok.

I met Anatoly when I visited Kiev in 2019 and we’ve stayed in contact and I really think he is a superb artist. Anatoly and I quickly formed a friendship. I’ve since managed to bring some of his paintings to Wales and feel confident that eventually I’ll curate exhibitions for him, in Wales, Romania and further afield.

The terminology of naïve art is interesting. Naïve artists have been variously referred to as Sunday painters or outsiders. The work itself has been called art brut, primitive or folk. In Ukraine they prefer the expression ‘pure art’

What do we see when we look at a painting by Anatoly Shmatok?

More often than not, immediately recognisable objects – such as an umbrella or a telephone or socks. Other objects range from pottery to bottles to toys and helicopters, but things are not as they seem. The artist, for example, thinks of a helicopter both as a machine and as a kind of bumble-bee pollinating star shaped lakes in a Ukrainian landscape.

While Anatoly’s animals are also recognisable – elephant, fish, rabbit, horse, cat – their role and their symbolism is wide ranging. The elephant can be a sign of age, wisdom, nobility and memory. A crocodile can signify ‘the enemy’. A cat may be an allegory for the Ukrainian people.

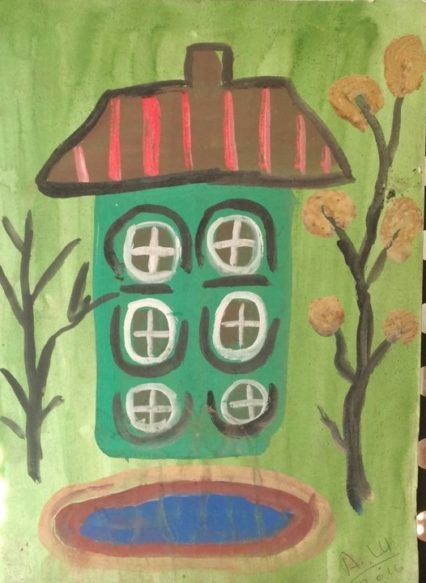

More complicated subjects are equally obvious and mysterious when rendered by Anatoly Shmatok – here is a house, here a village, a church, a river, a tree. There are flowers, single, in bunches in vases, in the garden and in pots. They are full of paradox, rich in in ambiguity; their precision is in the outline.

Anatoly’s lines are strong. They can confine and they can burst. They can be sharp or flowing. Infill comes with fields of colour or in patterns – bars, blobs, waves, spirals, asterisks. The paintings are intriguing because they articulate a visual gift that is passionate, childlike and unique.

Whether on paper or on canvass, Anatoly likes to work with sizes based on the international standard A series. As such he makes paintings ranging from A5 to A0 and all between. This method gives his various portfolios a sense of unity and of exuberance, compelling the viewer to closely examine his themes,

specific topics and repeated interests.

Some paintings are comments on contemporary life, others revisit his childhood, some are tributes to other artists. Space is important. Objects almost never overlap but are positioned separately. Single subjects are most often positioned in the centre of the canvas.

There is a tradition, among naïve artists (also known as ‘pure’ artists) in Ukraine, of emulating the paintings of acknowledged ‘masters’. Anatoly follows this tradition when he paints village scenes or develops themes such as a young man and woman meeting at the well; or a poet reading verses to a lady.

The paintings, especially of houses, are romantic and magical without being sentimental. Unlike many self-taught, naïve artists Anatoly Shmatok does not pursue minute detail. For him an illustrative brush stroke is enough. This can be readily seen in the paintings of houses and churches. A roof can be completed with a single mark, also fences and walls. Windows are improbably round.

Many elements are transparent and exist in outline only. People and the human form receive a similar unsophisticated outline, infill and patterning. They are also full of action.

In addition to their main subject many paintings are populated by systematic marks either within the subject or alongside. These marks generally indicate a surface, a table, wall or other type of background. Some paintings explicitly foreground these marks and do away with principal subject altogether.

It’s easy to see why the paintings of Anatoly Shmatok are enchanting. Whether the subject is simply a cat, a forest, or a memory of his grandparents’ home, the artist’s use of unmixed colour, strong line and decorative patterns emanate simplicity and wonder.

David Greenslade writes in Welsh and English and shares his time between Wales and Romania. Further information about the work of Anatoly Shmatok is available from David.