Twenty years after its release, The Holy Bible by The Manic Street Preachers has become a classic. Craig Austin looks at the reasons behind this cultural phenomenon.

Don’t be ashamed to slaughter / The centre of humanity is cruelty

The definition of an improvised explosive device (IED) is a home-made incendiary weapon constructed of conventional material, yet one deployed in a wholly unconventional manner. In many ways it equally characterises the intent and motivation of four prematurely world-weary twenty-something men from the South Wales valleys during the intensely single-minded gestation of an album the cultural standing of which has escalated exponentially in the intervening twenty years. As much as The Holy Bible exemplified a sense of contrary otherness at the tail-end of 1994, positioned defiantly as it was at the cultural roadblock of the soon-to-implode Britpop zetigeist, it has subsequently, undoubtedly, developed into a wholly anomalous cult of its own. An artistic construct that has seemingly transcended art itself; one that now acts – in the finest rock’n’roll tradition – as a perpetual and timeless rallying point for the disengaged and the disaffected to congregate around. Yet at the same time remaining a scabrous theatre of war upon which the habitual political extremes of left and right are compelled to make way for the politics of revulsion. An album that poses the age-old working class interrogation: ‘which side are you on?’, having long since ceased to care about the answer.

As the 21st century incarnation of Manic Street Preachers prepares to embark upon a brief UK tour dedicated primarily to the legacy of The Holy Bible it is perhaps fitting that the shows themselves are relatively restricted in number. In this they follow the addict’s credo of one being too many, and a hundred never being enough; an apposite approximation of two of the album’s key tenets, dependency and enslavement.

Predictably, tickets for these events (and I choose that word deliberately) sold out in a matter of minutes, a reflection of the reverence, awe, and devotion that this work now commands; emotions that chime perfectly with the darkly religious connotations of the album itself and its seemingly untouchable critical status as the Pet Sounds of human suffering. This is a huge record in its ambition, its reach and its staggering influence; an influence that as the bookshelves and diplomas of its acolytes will attest is not restricted to anything so limited as music alone.

Defiantly uncommercial – in spite of Nicky Wire’s bizarrely deluded belief that ‘She is Suffering’ had the potential to be the band’s ‘Every Breath You Take’ – it is an album that exists solely on its own terms, the band’s refusal to prostitute itself upon the meat-rack of mid-90s Britpop being an act that looks more prescient by the day.

Yet The Holy Bible is not entirely beyond comparison. Though received wisdom states that its core ingredients were drawn from the discordant post-punk well of Magazine, Siouxsie & the Banshees, and Wire, its lyrical themes are perhaps best reflected within both The Cure’s doom-laden 80s cult classic Pornography, and Infected by The The; the latter’s themes of disparate disgust driven by Matt Johnson’s chillingly visonary geo-political worldview. Pornography is the album that truly sets the template for the compounded themes of fatalism, anxiety and abhorrence that the Manics would later expand to take in more politically-charged subject matter; its opening line of ‘It doesn’t matter if we all die’ being one of a select few to rival The Holy Bible’s confrontational opening volley of ‘For sale? Dumb cunts, same dumb questions’.

The Holy Bible is an album whose volatile, claustrophobic subject matter – anorexia (‘4st 7lbs’), concentration camps (‘Mausoleum’), vengeance (‘Archives of Pain’) – weighs even heavier than the brutally unadorned subject of its startling Jenny Saville cover art, an image that speaks volumes about the unashamedly provocative lyrical and musical content within. It is perhaps the last gasp of craven political and artistic eccentricity from a band who would soon have its intellectual heartbeat torn away from it, and commence upon a significantly more commercial path to public awareness. The political themes remain, yet in more recent years the band’s politics have been distilled down to a core essence of traditional ‘old Labour’, the steadfast cornerstone of its members’ profoundly influential childhood in 1970s Blackwood; and notwithstanding the glitter-tinged ‘hammer and sickle’ iconography of its own formative years and the subsequent foolhardiness of the ‘our men in Havana’ excursion, it probably always was.

Yet in spite of the Soviet imagery that underpins so much of the album’s artwork and merchandise, The Holy Bible is anything but the left-wing text it is often mistakenly assumed to be, its ruthless political worldview wilfully defying history, tradition, and at times, even logic. It is a work of intentionally reckless extremes and outright contradictions, its themes swiftly careering between victimhood and Nietszchian retribution, the untethered influence of libertarianism never far from its scarred coalface. The intimate and tragi-delicate personal control that Richard Edwards presents so astonishingly within the lines of ‘4st 7lbs’ – ‘I want to walk in the snow, and not leave a footprint’ – at jarring odds with large swathes of much of the album’s content; passages steeped in horror and loathing in which Edwards presents himself as judge, jury, and unashamed executioner – a man with the seemingly divine right to occupy the gaping chasm where truth and justice once resided. He is after all ‘an architect’, ‘a pioneer’, a man who ‘spat out Plath and Pinter’, and one who in the sampled dialogue of JG Ballard (himself explaining the rationale behind his dystopian 1973 novel, Crash) ‘wanted to rub the human face in its own vomit and force it to look in the mirror’.

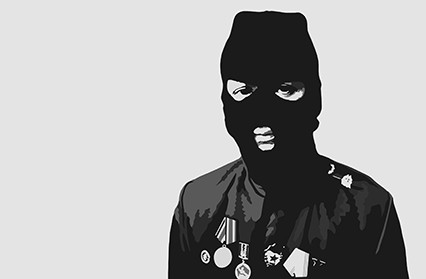

Though it will forever be revered as the most revolutionary moment in the band’s volatile back catalogue, its themes were not previously unexplored ones; just more extreme versions of what had gone, or been hinted at, before. The glitter, spray-paint and white Levis of 1991 having long since been replaced by the scar tissue, camouflage paint and disjointed military garb of a band who were now taking to the stage to the mournful strains of Carl Davis’s theme to The World at War, the uncomfortable and ominous Sunday afternoon soundtrack to many a 70s/80s childhood. Most illustrative of this is the aching melancholy at the heart of ‘Die in the Summertime’, the recurring heaven/hell leitmotif that had been utilised since the band’s earliest days to represent the cruelty of the passing of time and the purity of youthful innocence over crushing adult anxiety:

Childhood pictures redeem, clean and so serene

See myself without ruining lines / Whole days throwing sticks into streams

It’s a fixation whose delicacy belies the song’s jagged opening salvo of ‘Scratch myself with a rusty nail / Sadly it heals’ and one that Edwards chose to explore at length with a bemused and progressively unsettled Paul King during an MTV interview at the 1994 NME ‘Brat’ awards not long after the death of the band’s mentor and co-manager, Philip Hall: ‘I think the older you get, the more life becomes more miserable,’ he states. ‘All the people you grew up with die. Your parents die, your grandparents die, your dog dies, your energy diminishes, there are less books to read, there are no more groups to discover; you just end up a barren wasteland trying to find something new, which never really occurs’.

In a similar vein, and crucially for an album with overtly biblical overtones, it offers no hint of comfort in the notion that the meek shall inherit the earth. ‘I still stand for old ladies’, James Dean Bradfield avows within the remarkable ‘Yes’, during sections that exist in lieu of a conventional chorus; a pointed and thoughtful act seemingly in defiance of a presumed reality in which decency is exploited, and kindness is regarded as a fundamental weakness. In this sense, the candid childhood photographs of each band member that fleetingly populate the pages of the album’s lyric booklet act as a progressively fading representation of a more innocent time, a better place.

As astonishing and timeless as this album remains, in true Manics tradition The Holy Bible strives for magnificence but just falls short; imperfection being in itself a primary tenet of the MSP doctrine. ‘She Is Suffering’ remains a Manics-by-number plodder that only truly hints at its atmospheric potential via its Cure-esque (yes, them again) U.S. mix; the band’s preferred treatment of its work, and one now widely available thanks to a series of anniversary reissues. ‘PCP’, by comparison, remains what it always was, a more sophisticated take on 1990’s rama-lama ‘New Art Riot’ single, its lyrical intent filtered through the reactionary worldview of a hyperactive Richard Littlejohn. Yet these minor criticisms aside, it is hard to disagree with the music critic Keith Cameron who famously contends that The Holy Bible exists as ‘a triumph of art over logic’, and whilst this remains a concisely accurate assessment of this towering creative landmark, it palpably begs a bigger, yet much simpler question – surely all art should be this way?

original illustration by Dean Lewis