The tribute to Meic Stephens of July 23rd praised the quality of the writing that ran across the obituaries. That quality continues in this third collection, itself posthumous, of 41 obituaries from the years 2012-2017. The original publishers were The Independent in the main, with four in The Telegraph and one in Barn.

Variety of subject is inevitable, the obituarist going where his women and men lead. The politics of Wales are revisited. When Gwynfor Evans took Carmarthen in the by-election of 1966 the Labour candidate was Gwilym Prys Davies. “His defeat was a personal blow for Davies,” writes Meic Stephens, and he continues in analysis of the factors of defeat. A flair for the hustings and a common touch on the doorstep are little connected to capability for office. “I couldn’t see things in black and white,” Davies confessed.

Politics do not come in easy category of virtue. Stephens reports on John Davies, historian Bwlch-Llan, as “having no taste for confrontation and public disorder, and he played no active part in the law-breaking and prison sentences that followed over many years.” Stephens adds that they remained good friends, Davies being best man at the author’s wedding.

Stephens’ elegant essays also capture moments of importance in cultural history. Meredydd Evans was one of three who switched off the Pencarreg transmitter in protest against Westminter’s foot-dragging on S4C. He was also the force behind television’s Fo a Fe. “Ryan Davies beery, loquacious, lurcher-loving, Marxist collier from South Wales came into weekly conflict with a sanctimonious, organ-playing, teetotal, Liberal deacon from the north.” Llion Griffiths took up the editorship of Y Cymro in 1966, held the role for 22 years and was a leader in protest against the 1969 investiture. Nigel Jenkins was jailed for 7 days for cutting the fence at Brawdy and then refusing to pay the £40 fine.

The obituaries retain their vividness of description. Alison Bielski: “A private woman who took pains to guard her personal life against enquiries from nosy parkers and the plain prurient, she found solace in playing the organ and harpsichord, and in baroque music and the game of chess. Tony Conran was possessed of a “powerful intellect, cheerful disposition, and passionate devotion to what he saw as the art of poetry and the poet’s function, which he expounded with a stamina and erudition that usually reduced any opposing view into stunned but respectful silence.”

In mid-Wales Glyn Tegai Hughes was the long-standing custodian of Gregynog. “It was several years before the abstemious warden, a zealous Wesleyan lay-preacher, would apply for a license to open a bar at Gregynog, thus obliging some of the more bibulous house-guests to go to ingenious lengths when smuggling in their own bottles. In the early days of his wardenship the peaty water served at table from a private reservoir behind the house was known as Château Tegai.”

Here as elsewhere Meic Stephens is not just recorder but participant in cultural life. He remembers the photographs in a Butetown classroom where Betty Campbell was head teacher. He is a post-graduate in Bangor when he encounters Tony Conran. “I first had a taste of his rigorous dialectic in 1961.” The acquaintance with artist John Uzzell Edwards goes back to the same era. “In 1962 I was living in Merthyr Tydfil and he was in Deri, just over the mountain, where he had been born.” He is the artist’s first ever purchaser, paying five guineas for an ink-and-wash drawing of a pit-head.

A review of More Welsh Lives may close in exactly the same way as its predecessor. “The obituary is a sub-set of the category of essay. The essay may be art, albeit a minor one. The 41 pieces in “More Welsh Lives” are craft but they are also fine art.”

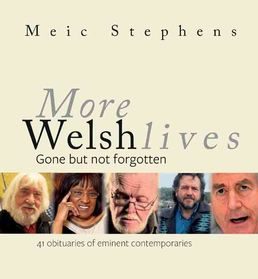

Meic Stephens