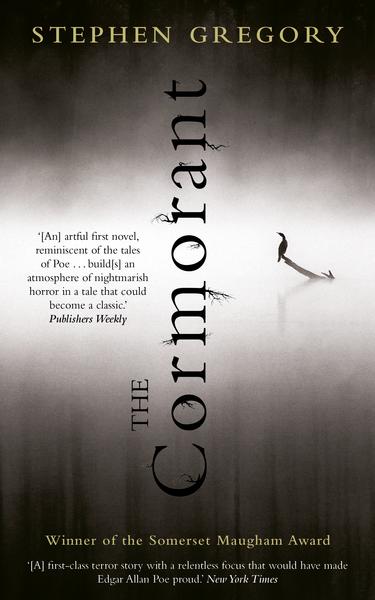

Welsh horror novelist Stephen Gregory reflects on the inspiration behind his award-winning 1986 debut novel, The Cormorant, and gives an insight to the influence the book has had in the many years since its first publication.

I remember I was homesick in North Africa, twenty-three years old and teaching English in a shabby, side-street language school. Young and homesick, and in the evenings drinking red Algerian wine and writing poetry… a poem about a cormorant, when I was longing to be home in England or breathing the salt air of a beach in Wales. I was trying to catch the paradox of the bird, its dual nature… its satanic silhouette as it stood on the rocks and dried its cloak of wings, its silvery sleekness as it dived and hunted underwater.

I remember a few years later, doing my teaching practice in Dorset… bitterly bleak in January, huddling in the evenings in a pub in Lyme Regis. The landlord had broken his wrist and had a steel pin inserted, and from time to time his professional cheeriness was spoilt by a stab of pain and a violent mood. I wrote a story about him… he found an oily cormorant on the beach and brought it into his bar, and somehow its quirky nature, its croaks and squirty mutes made him calm and sane.

And when I had the courage to quit the security of teaching, to rent a caravan in Snowdonia and try to write a book, the cormorant was still with me. The same essential paradox of the bird intrigued me. Its dual nature — its beauty in the water and yet its sinister gluttony — appealed to me as a subject for another, longer story. Through my first winter in the Welsh mountains I wrote and rewrote the novel; it grew darker and odder in its re-writing, and my agent sold it to the first publisher to read it.

The Cormorant has proved strangely resilient. Over thirty years since I wrote the book, it still provokes responses and interest. In its first publications in the United Kingdom and the United States and in translations, it had flattering reviews and I received some vile, anonymous hate mail. On the same morning I sat in the sunshine beside the river Gwyrfai and opened a letter to say that the book had won the Somerset Maugham Award, I had a scrawly, handwritten note to wish that I would rot in hell for writing such an obscenity. I was excited by both.

Since then, the book has been made into a gem of a television movie, directed by Peter Markham and starring the Oscar-nominated actor Ralph Fiennes. Peter came to talk to me about the project, and even before he’d stepped through the door of my cottage on the Foryd estuary a few miles south of Caernarfon, he told me he was thrilled about the book but of course we would have to change the ending. The book is small and dark and sinewy, with a shocking climax; for the movie we rewrote a treatment and the script was opened up with more amenable characters and a different, less disturbing resolution. Peter made a lovely, haunting film, but it remains an ambition of mine to see the essential nightmare of the novel put onto the screen.

The Cormorant aroused the interest of the director William Friedkin, infamous for The Exorcist. He’d found the book in a small-press American edition and liked it so much he flew me to Hollywood to write a screenplay for him at Paramount Studios… he liked my ideas and treatments, but my script spiralled into what he called ‘development hell’ and I came home to my novel-writing in Wales. Years later, parts of the screenplay are just recognisable in a horror B-movie which went straight to video, but I cherish the memory of my time there and the tiny imprint my material has left on the Hollywood film industry.

Birds, and the wild countryside, especially the woods and beaches and mountains of Wales… it’s the material I’ve loved to work with and use as the setting for my stories. One review had said that my writing was a fusion of Stephen King and the English nature-poet Ted Hughes, and the cormorant was the perfect foil for my first book. Since then I’ve tried in different novels, with different degrees of success, to capture the essence of other creatures as a way to open up the flaws and weaknesses of my human characters. In The Blood of Angels, an ammonite or a brittlestar or even a natterjack toad might have a special significance. In The Woodwitch, the protagonist is obsessed with the eerie, luminous growth of a gruesome fungus. In Plague of Gulls, a young man and the seaside town he lives in are bullied by black-backs. In The Perils and Dangers of this Night, a boy trapped in an old boarding school finds a little solace with his rescued jackdaw. And in The Waking That Kills, the miraculous, mysterious swifts, known as ‘devil birds’ by country folk, are the stuff of a midsummer nightmare.

The Cormorant is still bringing unexpected letters and offers into my email inbox. It’s about a young man, who, like me, gave up school-teaching to go and live in the mountains of Snowdonia… who, like me, was confronted by the vagaries of winter in Wales and the unpredictable moods of the weather. Unlike me, my narrator encountered such an unsettling horror that everything he loved most was threatened with destruction. Not in the cormorant, not in the bird itself which preoccupied and obsessed him… but in his own imagination and the dangerous, deadly cracks which opened within it.

It’s a brooding, confronting tale, perhaps too uncomfortable for a squeamish reader, and, thirty-odd years since I conjured it from its earliest manifestations, it still provokes a strong reaction. Like the bird, the book is beautiful and ugly, intriguing and upsetting, appealing and appalling, in its different, changing moods.

Stephen Gregory

The Cormorant by Stephen Gregory is available now from Parthian.

Recommended for you: Wales Arts Review’s Flash Fiction collection featuring original works from Cynan Jones, Nigel Jarrett, Richard Gwyn and many more of Wales’ best literary talents.