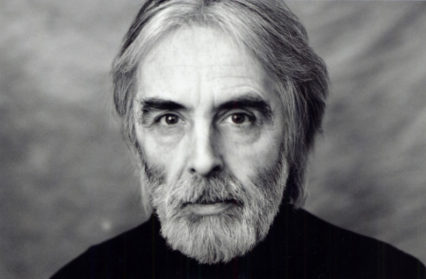

Michael Haneke | Jim Morphy looks back at film-maker Haneke’s thought-provoking career and the films which left a big impression.

Michael Haneke’s Amour has received such unadulterated praise right across the board that it is likely to have left the famously provocative director a little disconcerted – he’s never before seemed happy to leave the critics and the audience so unquestioningly contented.

Amour is, at heart, an achingly beautiful love story. That’s not to say the film isn’t unflinching, desperately sad, and, at its finale, devastatingly violent in its depiction of an elderly couple’s domestic life as wife Anne (Emmanuelle Riva) suffers a series of strokes and husband Georges (Jean-Louis Trintignant) struggles to care for her. ‘Things will go downhill, then it’ll all be over’, as Georges says.

But, certainly, the tenderness of Amour would seem to be a departure of sorts for the director most famous for his cold examinations of screen violence and the fault lines of European bourgeois society.

The success of Amour provides reason to look back over Haneke’s film career and to chart his journey to the very top of cinema’s pile of practitioners. In doing so, it’s worth searching to see if Haneke’s heart has actually been on show all along, even if half-masked by horror and dread.

Haneke had long worked in television before, aged 48, making his first feature film. This experience is evident in the technical proficiency of his earliest works, the so-called emotional glaciation trilogy of The Seventh Continent (1989), Benny’s Video (1992) and 71 Fragments of a Chronology of Chance (1994).

Rarely can a début have been as bleak as The Seventh Continent. The film follows an outwardly-appearing sound-of-mind young family in its methodical planning of, and act of, joint-suicide. As is consistent throughout Haneke’s oeuvre, we receive little in the way of backstory giving a tidy psychological explanation for the characters’ behaviour. Instead, Michael Haneke is interested in showing actions and consequences. At times, the film is numbingly, and intentionally, dull in its depiction of everyday life, with the car wash, the stove, the garage, and the dinner table all recurring images of the family‘s comfortable (and exhaustingly mundane, we’re perhaps led to think) existence. Admittedly, such scenes may not be to everyone’s taste, but they bring the hypnotic rhythm evident throughout Haneke’s early work. The film builds to the suicides – and murder, we should say, in the case of the young girl, a character for whom a deep tenderness is apparent. The mother crying at her daughter’s death being a rare outburst of emotion in the film. The story’s final ‘action’ happens as a TV blares from the corner of the room. Screens, a bourgeois family, murder and suicide, and children involved in ‘adult’ acts: these are themes that would come to be seen throughout the filmmaker’s work.

71 Fragments of a Chronology of Chance is a collection of scenes that only truly come together in the film’s final act when we see that the characters are involved in a young man’s murderous rampage. Through fragments from their lives, we see that the characters are not only victims of the attack, but they are also, to varying degrees, victims of, and perhaps even partly responsible for, a society desperately ill at ease with itself – the type of society that breeds killers, we might think. This being a world beset with war, abuse and celebrity culture, as we see from the news streaming out of the film’s many television sets. 71 Fragments is not a fully satisfying watch in and of itself, but it is interesting to see Haneke experimenting with narrative, technique and theme in ways that will be more fully-realised in later films, particularly Code Unknown (2000), which sits as a kind of companion piece.

Of the loose trilogy, Benny’s Video is the one that now holds up best. It is an utterly mesmerising work. The film follows a violent-film obsessed spoilt teenager as he records his life through video cameras. We, the viewer, watch on one of his screens as he kills a young girl in his bedroom. His parents assist him in covering up the murder. Again, emotional outbursts are rare in this film, so when they do come they are more powerful because of it. And, again, a mother’s tears are used to bring a degree of empathy. Benny speaks openly only once – tellingly, it is to one of his video cameras. The lack of genuine communication between the family is tangible, drawing a near-sympathetic reaction from the viewer even though we know of the despicable acts. The film remains truly shocking, and even if in the unlikely event Haneke was doing something as deeply flawed as drawing a direct link between watching violent films and committing violence, the film retains a rare power.

Once long unavailable in Britain, The Castle (1997), a brilliant made-for-TV adaptation of Kafka’s classic, is the surprise treasure of Haneke’s back catalogue. Starring the late Ulrich Muhe (The Lives of Others) as land surveyor K, the work displays a stylistic straightforwardness (even if the story itself is, of course, anything but straightforward) that serves Haneke well. In this approach, we see a template for some of Haneke’s later work, such as The White Ribbon (which itself was first conceived as a 3part TV serial). K’s ‘helpers’ bring an unlikely physical comedy to Haneke’s work.

‘Anyone who leaves the cinema doesn’t need the film, and anyone who stays does’, Michael Haneke famously said of Funny Games (1997), his most controversial critique of screen violence and the conventions of Hollywood thrillers. The film lays bare the slow humiliation and torture of a holidaying bourgeois family by two well-spoken strangers. One of the killers winks at, and speaks to, the camera, and when things go the mother’s (and the audience’s) way he rewinds the action to carry on his violence as planned. You see, the family members aren’t the only targets here, as Haneke has us, the eager devourers of screen violence, firmly in his sights. Haneke has rightly taken a hammering from many quarters for the patronising and lecturing tone of the film. However, the work still deserves plaudits, if only for Haneke’s mastery of the camera and his skill in building suspense and manipulating the viewer’s emotions, whether to bring fear, sympathy or even an incongruous sense of amusement. A scene in which the maimed father (Muhe, again) asks his wife’s forgiveness is truly heartbreaking (if you‘re still in the fictional story, that is). The film’s tricks now seem deeply infantile when compared to the maturity of his more recent works. Haneke made an English-language near shot-for-shot remake of the film, with Naomi Watts and Tim Roth two of the leads.

Code Unknown marks a turning point in Michael Haneke’s career. Here he shifts to a French setting and French production. Also, Haneke’s primary focus moves from screen violence towards a wider socio-political examination of society – particularly issues around race and racism. The film follows the lives of those involved in an altercation on a Paris street, including actress Anne (Juliette Binoche) and a Romanian illegal immigrant who is deported following the incident. Class – or perhaps that should be power – dynamics in society are always central in Haneke’s films. Again, images of war and other horrors around the world are peppered throughout the film. Code Unknown is a brilliant work, and one that gives a sense of where Haneke’s work had been and where it was heading.

The Piano Teacher (2001) is a largely faithful adaptation of Elfriede Jelinek’s superb 1983 novel that tells the dark and deeply disturbing story of a repressed professor of music seemingly hell-bent on self-destruction. As typical of Haneke, we get little psychological explanation for the protagonist’s (Isabelle Huppert) behaviour. Instead, we get to observe in explicit detail her self-harming, her bed-sharing with her domineering mother, and her masochistic relationship with a smitten student. The viewer is then left to make of all this what they will. Sight and Sound has said it can be read as a feminist text: being ‘an extremist vision of what it means to lack social, sexual and cultural power’. Many scenes are difficult to watch. Haneke always revels in daring us to keep looking at the screen – a brutal rape scene here reminds us of watching, for example, the murder of Benny’s Video and the casual ultra-violence of Funny Games.

Many scenes are difficult to watch. Haneke always revels in daring us to keep looking at the screen

Time of the Wolf (2003) is Haneke’s take on the post-apocalyptic world where it’s (nearly), everyone, for themselves (we’re not too far from Cormac McCarthy’s The Road or Jim Crace’s The Pesthouse). We start with a family entering what, in better times, was their holiday home. We sense that they are retreating from something. If you’re middle-class and the holidaying sort in a Haneke film, then god help you. The customary Haneke explosion of violence forces the family – minus Dad – to take to the road and fend for themselves. As ever, compassion is rare, but when it comes it is often through the family’s dealings with a young boy, who is also drifting. When Haneke shows his heart, it’s generally for children. Although we should say, Haneke is also never shy in showing us that children are liable to do the most heinous of things. Children are always full players in Haneke’s films. The closing scenes in which a naked boy is stopped from sacrificing himself to the fire on a railway line (the only source of hope) is as moving – as humane – a finale as you could hope for. Time of the Wolf wasn’t particularly well-received on release, but it stands up as a more than impressive work.

While Hidden (2005) retains many Michael Haneke staples – screens on screen, a burst of sickening violence, the bourgeoisie exposed – we see in it a new maturity from the film-maker. With it, he achieved the distinction of making his most accomplished, his most thought-provoking, and his most accessible film. It is an amazingly assured work. The best film of 2005 surely, the best film of the decade perhaps. Our lead Georges (Daniel Auteuil) receives a series of secretly-filmed videos of his own life, causing him and his wife Ann (Juliette Binoche) to get increasingly distressed. As Georges seeks to find out who has sent them, the action reveals Georges to be the culprit of a related act from his childhood days. Guilt and, particularly, the denial of responsibility are key themes here. Georges’ story is used to allow a wider exploration of the cracks in French society, with Haneke describing Hidden as a film exploring the effects of the country’s occupation of Algeria.

Hidden is an amazingly assured work. The best film of 2005 surely, the best film of the decade perhaps.

Haneke followed Hidden with the stunning – and Palme d’Or winning (like Amour) – The White Ribbon (2009), set in a north German Lutheran village just before World War I. The film explores the violence, rebellion and evil beneath the surface of an apparently peaceful society. Children thinking and acting in ways more associated with adults – for good and for very bad – is again to the fore here. Through the explicit focus on children, and a sympathetic narrator, we see more of the softer side to Haneke than we’ve previously been used to. Arguably, that softer side has become apparent yet further in Amour. Although everything should be kept in perspective – such things as softness, tenderness and love have slightly different meanings in Haneke’s world than in most people’s. Or, at least, they manifest themselves in different ways.

Like Hidden, The White Ribbon is ostensibly a whodunit, but we never find out who did do it. Instead, the puzzle is used as a way of exploring the dynamics of a community, and society at large. Nearly everyone would seem to be guilty of something, be that theft, beating, child abuse or mental torture. Michael Haneke has said that the film is about the kind of behaviour – the kind of rancour – that allowed Germany to take the path it did in the decades following the film’s end.

Hidden and The White Ribbon are both 10 out of 10 films. For many, he has followed them up with another in his story of love, loss, mortality and home. Certainly, Amour is another classic, although, by virtue of its tale, it lacks the narrative drive and scope of the other two films. Amour also has a few self-reflexive touches – the longheld shot when the action is elsewhere, the dream sequence – that it could do without. Haneke, it seems, just can’t help but remind us we’re watching a film – a film that he is the master of.

But it’s not necessarily a bad thing to be reminded that you’re watching a film by the genius director, as it means you’re in safe hands. Even if natural-troublemaker Michael Haneke would surely still like to think his hands are anything but.