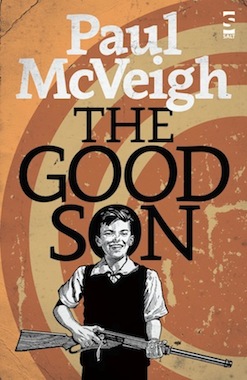

240 pages. Salt, £8.99

Mickey Donnelly, the central protagonist of Paul McVeigh’s debut novel, was born on the first day of the Troubles (‘it was you that started them, son’, his Ma says with typical black humour), meaning that sectarian Belfast is the only reality that he has ever known. He watches a lot of light-hearted, slapstick American TV like Abbot and Costello and Laurel and Hardy, and dreams of escaping to the almost otherworldly-seeming US. He obtains a scholarship to a good school that he desperately wants to go to – partly because he is a very bright pupil but largely to avoid the well known violence of the local secondary, St. Gabriel’s. He is unable to go, however, because his father consistently spends all of the family income on alcohol, which means that, scholarship or not, his family still wouldn’t be able to afford the new uniform and extra travel money required. St. Gabriel’s fills the eleven-year-old Mickey – who dearly loves his younger sister and his Ma and perhaps most of all his dog – with dread. The aggressive machismo exhibited by the local boys who attend it seem both foreign and incomprehensible to him.

Mickey Donnelly, the central protagonist of Paul McVeigh’s debut novel, was born on the first day of the Troubles (‘it was you that started them, son’, his Ma says with typical black humour), meaning that sectarian Belfast is the only reality that he has ever known. He watches a lot of light-hearted, slapstick American TV like Abbot and Costello and Laurel and Hardy, and dreams of escaping to the almost otherworldly-seeming US. He obtains a scholarship to a good school that he desperately wants to go to – partly because he is a very bright pupil but largely to avoid the well known violence of the local secondary, St. Gabriel’s. He is unable to go, however, because his father consistently spends all of the family income on alcohol, which means that, scholarship or not, his family still wouldn’t be able to afford the new uniform and extra travel money required. St. Gabriel’s fills the eleven-year-old Mickey – who dearly loves his younger sister and his Ma and perhaps most of all his dog – with dread. The aggressive machismo exhibited by the local boys who attend it seem both foreign and incomprehensible to him.

The area in which Mickey and his family live is to all intents and purpose the middle of a war zone:

I have very clear instructions. Don’t go to the top of the street cuz there’s always riots. Don’t go to the bottom of the street cuz there’s no-man’s-land and there’s always riots. Don’t go near the Bray or the Bone hills cuz that leads to Proddy Oldpark where they throw stones across the road from their side. Don’t go into the aul houses cuz a wee boy fell through the stairs and broke his two legs. I think his neck too…

Early on in the book Mickey’s family home is raided by the British Army, who do regular spot check searches in the area, partly to look for IRA ammunition but also partly to intimidate. On this occasion they find an ancient child’s balaclava and use it as a reason to take Mickey’s teenage brother in to custody and deliver a savage beating. Soon after, Mickey’s brother becomes radicalised by the IRA with such inevitability that it almost feels as though this is something that the army themselves had wanted to achieve.

It is on these levels that the book is particularly successful. Because everything is viewed through the lens of eleven-year-old Mickey, everything is seen from an entirely innocent perspective. Thus Mickey can’t understand his older brother’s behaviour but the reader can. Or, for instance, when he and a group of children come across a young woman that has been tarred and feathered by the IRA as punishment for sleeping with a British soldier, Mickey’s reaction is at once both moving and disturbing. While he feels the substantial degree of empathy towards the woman that we have come to expect from his character, his lack of surprise, and his acceptance of this kind of brutality as a part of everyday life makes the inhuman nature of the act seem all the more vivid and unsettling to the reader.

Indeed, perhaps two of the characters that Mickey most calls to mind are Scout Finch and Paddy Clarke, and this is a book that shares an affinity with the two novels which those characters call home. Mickey’s child’s eye perspective ironically serves to highlight the childishness of the adults – from whichever side of the divide – in the Northern Ireland conflict, in much the same way that Harper Lee used Scout to focus her readership on the issue of racism in the Deep South, or Roddy Doyle Paddy Clarke to draw his readers to the subject of the effect of marital breakdown on a young child. It’s such a good idea to use this as a lens through which to view the Northern Ireland conflict that it almost takes you aback that no one has thought of it before. Books based in Troubles-era Northern Ireland often tend to be – and maybe necessarily so – grim, unrelenting affairs, focussing on the absence of hope rather than its possibility. The Good Son is different in that Mickey is, as McVeigh himself has said, ‘like [a] tiny sign of life in a desolate landscape.’

Looking at the Northern Ireland conflict from the point of view of a child – and a particularly charismatic, extremely sweet-natured child like McVeigh’s protagonist – has the effect of throwing the conflict into sharp relief. Not only does it make violence and hatred look as absurd and anachronistic as it certainly is, but it also goes a very long way towards humanising the conflict, and to divesting it of the black and white terms in which it is so very often drawn. As such The Good Son is also a powerfully resonant novel, serving to draw parallels with other conflicts around the world, and reminding us that the suffering of children is always, always at the heart of warfare. In some cases the children that survive will perhaps end up being radicalised like Mickey’s brother Paddy, and in other cases they will maybe, like Mickey, try to find some way to make kindness and sensitivity work in the most forlorn of surroundings.

McVeigh has said that he approached Mickey’s character as an actor might and this shows in the writing, which is frequently imbued with a high degree of emotion. In some ways this is a risky strategy for a writer to take as it can make the necessary quality of authorial detachment harder to attain. That McVeigh inhabits the character of Mickey with such verve and uninhibited gusto and yet manages to almost always maintain this quality of authorial distance constitutes a remarkable achievement. Because, put simply, Mickey Donnelly, ‘the good son’ of this very fine debut novel’s title, is an unforgettable character. And one that, like Scout Finch and Paddy Clarke before him, can teach us a great deal about the way that we, as adults, look at the world around us.

Image of Paul McVeigh: Original artwork by Dean Lewis after an original photograph by Roelof Bakker.