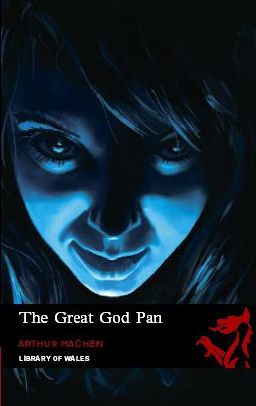

Jon Gower continues his journey through the Library of Wales collection this time he casts his critical eye over the horror and fantasy novella from Arthur Machen, The Great God Pan.

In the world of horror fiction one would be hard pressed to find a more positive cover blurb than the one that’s emblazoned on the back of The Great God Pan: Stephen King calls it, unequivocally ‘One of the best horror stories ever written.’ The story first appeared in 1894 when its author was a complete unknown who had just finished translating Casanova’s memoirs and was living in, or rather eking out an existence in London on a small inheritance. Here The Great God Pan finds itself sharing space with two of Machen’s other stories, namely ‘The White People’ and ‘The Shining Pyramid.’ As entry-level Machen goes this trio is pretty definitive.

So what makes The Great God Pan such a good story? To begin with Machen is writing out of his time, almost against the age: he is a very early modern writer, as this tale first saw the light of (gloomy, ill-feted) day in the eighteen nineties, when Machen was a complete unknown. Since then it’s become a benchmark tale and had a discernible and often direct influence on a substantial cohort of horror writers. Peter Straub wrote his ‘Ghost Story’ as an extended tribute to it, while M. John Harrison, in a spirit of direct homage, called his reworking of this dislocated and dislocating tale The Great God Pan. And there are others, too. Frank Belknap Long wrote a sonnet about reading Machen while Stephen King not only sang its praises but modelled one of his own stories, called “N” very closely on it. From Clive Barker to Charles Williams, W.B.Yeats through Arthur Conan Doyle to Oscar Wilde, writers have been swift to sing the praises of Machen, emulating and admiring him at one and the same time.

by Arthur Machen

So what is it about this book that attracts both the plaudits and laurels so magnetically, and especially draws so many writers onto the fields of praise? The Great God Pan is an out-and-out weird story, or novella, detailing the consequences of a medical experiment conducted to investigate the sources of the human brain. The laboratory has all the apparatus of B-movie sci-fi, with oily fluids and green phials, a chair with levers and, of course, there’s a young woman seated in it. What seems ostensibly to be some sort of trepanning goes horribly and fatally wrong, so that the young woman who is the guinea pig ‘sees’ the great God Pan but dies as she does so:

Suddenly, as they watched, they heard a long-drawn sigh, and suddenly did the colour that had vanished return to the girl’s cheeks, and suddenly her eyes opened. Clarke quailed before them. They shone with an awful light, looking far away, and a great wonder fell upon her face, and her hands stretched out as if to touch what was invisible; but in an instant the wonder faded, and gave place to the most awful terror. The muscles of her face were hideously convulsed, she shook from head to foot; the soul seemed struggling and shuddering within the house of flesh. It was a horrible sight, and Clarke rushed forward, as she fell shrieking to the floor.

It is this dead woman, perhaps, who subsequently keeps on appearing to people and precipitating their deaths in turn, often at their own hands (there are echoes throughout the tale, and sometimes direct references to the grisly Whitechapel Murders, carried out by ‘Jack the Ripper’ in London’s East End between 1888 and 1891). Structurally The Great God Pan is a twisted melange of stories and journals and within stories: The Great God Pan is veritably a Matryoshka confection, a Russian doll full to the brim with seeping, foggy menace, inexplicable deaths and resurrections.

Coupled with it in this LOW volume are two other tales, namely ‘The Shining Pyramid’ and ‘The White People.’ The first concerns a young man who tries to disinter the meaning of a collection of strange stones that materialise on the edge of his property, while ‘The White People’ leafs through the troubling and unsettling pages of a young girl’s diary, recounting tales told her by her nurse, and her increasingly deep delvings into magic. It, like the other two stories, creeps under the skin like a chigger, one of those banes of south American life, laying eggs there, uncomfortable to begin with, then silently painful before the inevitable and horrible eruption of insect life. Machen won’t show you it all, he is not an explicit writer, where the horror is all described, splatter by splatter. Rather he nudges the reader forward with studied nuance and telling detail, setting his sentences like traps, like the blackest of spiders.