Jon Gower nominates Glyn Jones’ The Valley, The City, The Village as the next entrant in our series to find the Greatest Welsh Novel.

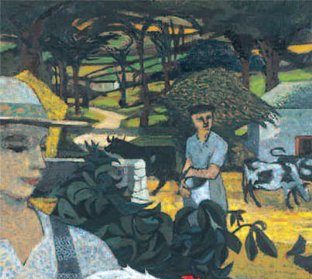

I remember the novelist Euron Griffith raving about Glyn Jones’s The Valley, the City, the Village over a pint in Chapter but I didn’t get round to reading it despite his paean of praise. More fool me. I had no idea I was missing out on such a fabulous treat, a book which sings, which soars, written in prose that compares easily with Annie Proulx, James Salter, Wells Tower and the like, and scales the same dizzy and dizzying heights. The extravagant, poetic passages come as bravura flourishes, as if the novel – which first appeared in 1956 – has itself been painted and the author had just discovered a palette of colours and pigments that are new to the world. Which is thoroughly appropriate as the main character in this dense, Dickensian and memorably populated novel – with its Anna Ninety-Houses, its Dai the Fan and its big-nosed Auntie Tilda – is Trystan Morgan. He is a wannabe painter who is steered down a more rigid and less rewarding academic path than the one his heart desires.

The novel charts the course of his life, starting with Trystan’s early days in his gran’s cottage in a mining village in south east Wales. Here he comes under a lot of pressure to become a preacher, when what he really wants to do is paint people rather than save their souls. They say that painters, even the great ones, can never paint hands, but in luminous and tender prose Glyn Jones compares Trystan’s hands with those of his grandmother:

They were red and rugged, the hands of a labourer, their knotted erubescence evidenced familiarity with the roughest work, they seemed as though the coarse substances at which she had laboured had become an element of their conformation. Often, when I was older, and knew the meaning of those bony and inflexible fingers, I turned my gaze from them with shame and pity and watched my own painter’s hand, culpable, indulged and epicene, as it moved adroitly in the perfect glove of its skin.

The grandmother is just one of the characters extravagantly and vividly drawn in the book, an old lady who can appear almost god-like, ‘a tall black figure’ which ‘seemed to float out of that bonfire as though riding a raft of illumination.’ The language employed in creating the vignette of her owes more than a hint of debt to Dylan Thomas, for ‘she was my radiant granny, my glossy one, whose harsh fingers lay gently and sweet as a harp hand upon the curls.’ But this is not to suggest that Glyn Jones is in any way derivative of the boozy bard: in fact quite the opposite is true as Glyn Jones writes radiant prose that fair shimmers with epiphany and carries an often superior melody. Take this painterly description of a skyscape:

Over our heads as we cooked, large masses of lathery clouds were blown through the blue like frondent soap, silvered and convolved, sloshing vast bucketfuls of brilliant light over our whole mountain. The majestic swimming ridge on the far side of the wide valley rose convulsively into the sunshine; as I watched I saw it constantly sloughing the teeming cloud-shadows off its head and shoulders.

Jones isn’t scared of using arcane words and there are passages which carry a fair burden such as ‘conventicle’, ‘vedette’ and ‘eleutheromania’, which can bring to mind the language-scapes of Anthony Burgess at his most showy.

Trystan’s time at university finds him introduced to all manner of undergrad nonsense and clubbery, and he finds escape from the ministrations of the likes of academics such as Professor Ailradd, Dr Di Enaid and Professor Anfoesgar in extra-mural art lessons. There he learns to paint pictures with all the heightened sense of colour as that employed in full and rich measure by Glyn Jones, who can weave a tapestry of landscape that is so rich and textured, detailing ‘the glowing pastures of suede-smooth emerald; the furzy wool of gold-flecked, gorse-fleeced heathlands; and the chocolate acres under plough, formally embossed with lime in white studs arranged in rows along the tillage.’

Trystan fails his exams, falls in love with the wrong woman and brings twin disappointments in their train. He is an artist, and his place in the world is an awkward one. But we are on his side, wanting him to be allowed to create more beauty, find expression.

The Valley, the City, the Village is quite simply an astonishing achievement, moving deftly between a myriad registers of language, offering some breathtakingly bravura passages of prose, and plentiful evidence of a deeply sensitive, organizing intelligence at work.

It is, for me, the discovery of the Library of Wales series. It is a stunning work of art by a gentle, unassuming man I had the good fortune to know. Read it and weep, weeping at the sheer beauty Glyn Jones marshals and arranges, as he fills with luxuriant life every inch of his lush and lovely novel-canvas.

This piece is a part of Wales Arts Review’s ‘Greatest Welsh Novel’ series.