Despite numerous debates, the harp will always be linked to a Welsh identity. Bruce Cardwell’s The Harp in Wales explores just that: a book that focuses on the harp in the context of Wales. With an in-depth introduction to the historical importance of the harp, Cardwell gives a simplified and concise background to the instrument, looking at its structure, its development and its significance. Cardwell explores the old bardic compositions and the simplicity of the first harps made of wood and horse hair. He then traces its development to the more sophisticated instrument it is today. Around 1775, the first triple harp was made for blind harpist John Parry. This increased the harp’s popularity, but by the 19th century, it was beginning to decline due to the deaths of many famous makers. This then, is undoubtedly a signifier of the importance of the maker, and is one which Cardwell emphasises again and again by embedding biographies of makers between famous players; without makers, there would be no music. The book is extremely informative, yet not written in a way which excludes the non-harp player.

Cardwell’s introduction offers an engrossing history of the instrument which is also very informative; it is displayed in a way that is not dependent on any kind of expertise. He follows the chronological historical developments of the ancient instrument, but brings it back to Wales, drawing on the laws of Hywel Dda and the stories of the Mabinogion. Cardwell tells the readers with confidence that if Cymru is ‘Gwlad y Gan’, then the symbol of song embedded within the country is the harp, thus implying its importance to Welsh identity. In the words of Professor Ieuan Jones, ‘the harp is more normal here than in many other countries.’ We may not today be that clichéd picture of a figure in a tall black hat playing a wooden harp – in fact, the players will be dressed in suits and ball gowns with a harp that is simply beautiful to look at. This old image however is more than just a stereotypical representation: it is an image that solidifies values still cherished today.

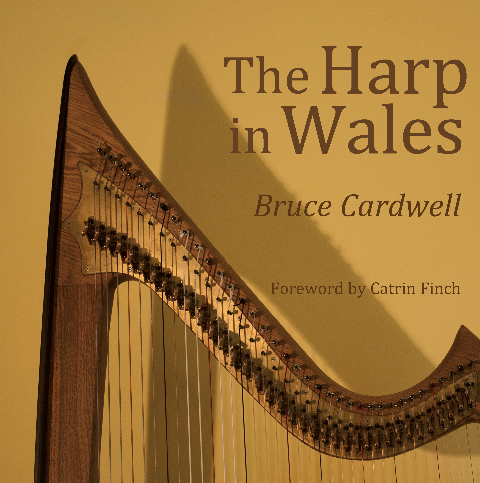

by Bruce Cardwell

Seren, 200pp., July 2013.

Foreword by Catrin Finch

The book goes on to introduce different players and makers in Wales, old and new, modern and traditional. From the iconic Nansi Richards to perhaps the more experimental Kay Davies, Cardwell really does cover it all. Nansi is described as ‘an encyclopaedia of the Welsh Countryside’. Nansi was such an icon in her day. Fascinatingly, when staying in America with Will Kellog, she told him that his name sounded like ‘ceiliog’ in Welsh, meaning cockerel, and told him to put a cockerel on his cereal packet. This was the origin of rooster we still see on the packet today. Her life was music, and to encapsulate that, on seeing the harp at Dolgellau’s folk festival in 1979, she said, ‘This is the climax of my life – seeing the triple harp taking its rightful place on the Welsh stage.’

Cardwell doesn’t present the makers and players in a significantly segregated way; he varies style and era in a way which seems to imply how relevant the harp still is today. It is also always brought back to a Welsh root, re-enforcing this idea as the harp as part of our cultural identity. Each segment for each artist has its own appeal. In a chapter on Nansi Richards, Cardwell includes many allegorical narratives which are familiar and funny. Catrin Finch is of course given her own chapter (and writes the Foreword), as she is considered one of the most widely recognised harpists in Wales today. Cardwell uses direct quotes from Finch making for a rich segment. Finch is largely considered to be a more modern harpist, moving away from the classical towards a more contemporary sound. In 2000, the post of Harpist to the Prince of Wales was revived, and of course, Finch was top of the list. This coinciding of the traditional post with the modern harp player is surely significant to the harp’s increasing popularity in modern Wales. Finch has played around the world, winning prestigious competitions in New York, for example, for her ability. This just goes to prove that the harp is a true representation of Welsh identity, and to be recognized around the world for its iconic sound is a privilege. It is refreshing to read of the new Welsh harp talent too like sisters Llinos and Alaw Jones, Nest Jenkins and many more. This vast inclusion of makers and players really does illuminate how constant the harp has been, and how it will continue to be in the future.

Cardwell’s style of writing is not one of an expert appealing to an expert, nor is it one of a specialist educating a non-musician. It is nestled comfortably in between, a sort of conversationalist tone runs throughout. The distinctive, well selected photographs really enrich the reading experience providing a sense of character, place and Welsh identity. Cardwell’s fantastic book speaks to everybody, and is a significant documentation of instrument that is so often associated with our country and is thus intrinsically linked to our cultural identity.