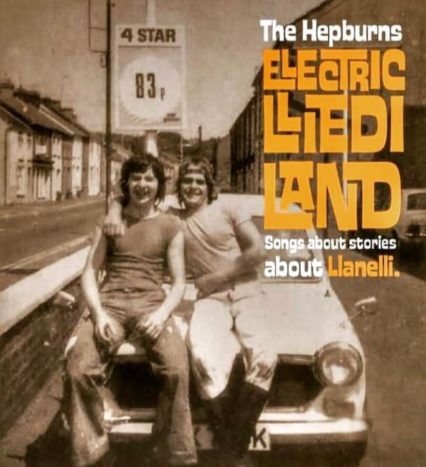

Gary Raymond speaks to The Hepburns to hear how lockdown shaped the creation of their album released in 2020, Electric Lliedi Land, and how the circumstances of the pandemic have now led to an international community, with their latest album, Architecture of the Ages, released on Spanish label Elefant Records.

Gary Raymond: Okay, so I think a good place to start is to ask what you guys were up to creatively when lockdown happened: Where were you at? Were you working on some stuff? Or were you sort of on hiatus?

Matt Jones: We’re always normally working on something anyway, and coincidentally, we just finished an album. But it was 20 tracks and planned as a double album, which we were going to release on the label that we were on at the time, which is an American label called Radio Cartoon. And it was, you know, that was a labour of love that we had written over a period of 18 months. It was produced and good to go, we’ve got a friend of ours in Tasmania who produced it. But then the pandemic intervened, so that’s where we were creatively.

So, it was kind of a landmark really, our next album. In the course of doing that we have perfected a way of working together which we never had before. Which, as it turned out was really useful during the pandemic because I was able to do a lot of the recording on my own with my iPhone, because I discovered GarageBand so I was here doing the producing process, and it was the first time I’d ever actually had any home recording devices at all. So, the microphone that I used for that particular album, like a lot of the vocals, or the keyboard, was all done on an iPhone.

Gary Raymond: Yeah, that’s really interesting because, obviously, what came about during the pandemic was this small idea of “why don’t we get a few people together and create some stuff”, and then this idea grew and grew into this much bigger project as more people got involved. Could you tell us about the evolution of the album [Electric Lliedi Land]?

Matt Jones: So, firstly, again, it was just an experiment of sorts – just using GarageBand and seeing what we could do with all the sounds. More than anything it was just actually having something there in the house, you didn’t have to go to a studio to record. So, developing that kind of skill after all these years. It was all a case of old dogs, new tricks, really.

But then, from that, a friend of mine was reminiscing with me about the time he and my brother went to see The Elephant Man in Llanelli. He was telling me it was a Sunday night, and they were kicking their heels looking for something to do. So, what do you do when you’ve got no money? You go to the Classic, which is what the cinema in town used to be called, and they sneaked in with a couple of cans, feet up on the seats – just like it says in the song. It’s obviously classic Hepburns material, really, a song based on an anecdote with some humour in it, and it captured the moment very well.

That literally was the genesis of it, apart from the other song ‘Floated’, which was one of the few songs on the album that wasn’t entirely based on an anecdote. So, I asked my friend Alan if he didn’t mind me using the cinema story, to see if it was okay to tell the world that he sneaked in the back of the Classic – (and kudos to him for sneaking in to watch a cult film like The Elephant Man). From then I started thinking, well hang on a minute, why don’t I ask two more people? So, that’s how the album originated, and it literally just burgeoned from there.

But my first memory of the pandemic was that it was quite a terrifying time. I had just lost my dog, Gwyn, who’d passed away, so it was a sad time for me and lockdown added to that. It felt like there was a threat hanging over you. It felt, in a way, like wartime didn’t it? I must admit, I kind of retreated, I wasn’t taking any risks at all. I think you were the same, weren’t you?

Les Mun: Yeah, yeah.

Matt Jones: I mean, with you, it was the same type of thing, wasn’t it? You had your family… you know, two of your kids are doctors…

Les Mun: Well, it was a very odd time, because if you remember the weather was fantastic. So, we were sort of out in the garden, and yet the two children were like, in the middle of ‘the gates of hell’, as it was being described in Italy. So, it was very odd.

Matt Jones: They were in London, weren’t they?

Les Munn: Yeah, they were in different hospitals. So, it was very odd in that respect, because we had a very quiet time down here, and yet they were seeing the other side of things… So, the opportunity to affect something like this was, you know, very important, to get an element of normality, I suppose.

Gary Raymond: So, for you guys it was very much a kind of reaction to the situation you found yourselves in. I mean, would you say it was an element of that but also, something was growing that felt like there was a bigger picture? Did you feel that you were providing something for a community of people who also wanted an outlet?

Matt Jones: Absolutely, yeah. I mean, we’ve mentioned the lovely weather, which is something I’d forgotten for a second. But yeah, there were all sorts of uncanny contrasts there.

Gary Raymond: Well, I’m having lots of conversations just generally about how we’ve all kind of forgotten what the first lockdown was like. Not forgotten, because obviously, we all have moments like you with Gwyn and those memories that we have attached to that time. But I think sometimes memory and trauma play different tricks on each other and, more and more as we’re having conversations about this, it seems we’re remembering lockdown as if it was a really long time ago, rather than just two years ago. There’s lots of things that are forgotten. I was interviewing Kevin Sinnott, the artist, and he was doing lots of paintings at the time about people out in the sun in this beautiful, warm spring and then then second lockdown was more wintery and hard.

Andrew Clement: That’s right, I mean I much preferred lockdown one. But it did have its own kind of flavour, partly to do with the weather and the strangeness of it. It was almost like a dream, and it felt like it was going to be a finite thing which would somehow just stop one day, and we’d all be set free, but that never happened and it just dragged on a bit.

Gary Raymond: Do you also think, in those early days, even though it was difficult to be cut off and to be isolated from loved ones and family members, that we were all doing it for what felt like the greater good. So, even though we were becoming isolated, it was about community?

Matt Jones: Exactly, yes. There was that sense of a common purpose, I suppose. But we were all definitely doing the right thing and we knew we were sort of looking after each other. At the same time, there were a lot of unexpected things that came from that time, and one of them was this project. We tapped into that strangeness, that uncanniness – the fear and isolation balanced out by a sense of community. For us, that brings material.

We’ve evolved over the years, to become a band where the songs are really like stories. We were ideally placed at that time to ask for stories to be able to adapt them, because that’s what we’ve always done. It’s not so obvious in past albums that they are based on real life things, but they are. They’re also based on Welsh experiences. It did feel as if one day we just asked for these anecdotes and they started coming forward and it was fantastic. I’d never been in that situation – despite the fact I was very used to writing stories based on real life events – it was amazing to be adapting other people’s tales.

There’s a sense of empathy that you feel with people, as I found out, when you’re adapting their story. It’s a completely different experience, you feel an obligation to them to tell the story, kind of as it happens, and at the same time, you find yourself up to the same old tricks, you know, writing a Hepburns tune, but it was great. It was the best songwriting experience of my life, easily.

Gary Raymond: Could you talk a little bit about the process of how it worked, being in contact with people and how you would interact and get the material and then turn it into a song?

Matt Jones: Sure. Do you know, that’s the first time in 37 years that anybody’s ever asked me about my songwriting technique, and that is a fact for you. People aren’t interested.

Les Mun: I’m always asking you.

Andrew Celment: I’m usually only asking you ‘how do you play this?’

Matt Jones: Well, the answer is, I was asking a lot – mostly on social media – if anybody could donate some tales. In terms of the parameters there weren’t many really, apart from just asking that they were stories mostly about Llanelli life, but West Wales was fine, it was definitely meant to have a West-Whalian focus, you know. It was meant to be about our community. It was about giving a voice to these people, and I know that sounds like a very hip way of saying it, but it was exactly that, that’s what I felt I was doing.

It could be about anything and I’d adapt it. I can do that really quickly, normally it takes me a day or two maybe to write a song, and adapting it was no different. It was just a more enjoyable process, that’s all. So, I’d get the anecdote from the person concerned via email, sit down with the guitar there and then, with the words first – it quite often is the words first, anyway – and then you work it out. Once you get your hands on a story idea, a lyric acquires a life of its own. You’re exploring rhymes, there are puns, you’re trying to inject some humour into it. There are all sorts of things that go on in the actual mechanics of writing lyrics; it’s not a million miles away from poetry.

Les Mun: There is one song where, like – most of the songs are telling the story, more or less – but there’s one song that is pure genius. He can take something mundane, like literally the noise from the guy next door, and just inject this world of fantasy into it. The one I’m thinking about is called, ‘Hey, Mrs. O’Shea’, which is about this cleaner asking this young lad to go and buy you her the latest Alvin Stardust song, which is a great story in itself, but the song ends up making reference to the cross-dressing glam rockers, and the next thing you know he’s on about the Rebecca Riots, and that’s genius in my book. That’s taking a mundane, good story in itself, to a totally different level.

Matt Jones: So that was literally an anecdote an old friend told me about this housekeeper they had because they lived on a posh road. Her name obviously was Mrs O’Shea, and it actually took place. But the conversation that’s in the song didn’t actually happen. So, you know, it’s not documentary song writing.

Gary Raymond: I’m interested in the fact that the brief you gave out to people was about anecdotes of the places that they grew up. It wasn’t about how are you feeling about lockdown. What inspired that approach? Rather than asking for thoughts about how crazy the world was at the time?

Matt Jones: It’s a very good question. And I don’t think I even asked myself at the time, really. I just knew I wanted anecdotes, but I have thought about it since. I think for me, as an as an artist, as a writer, anyway, it would have been the wrong thing to have written directly about the situation that we were in. I don’t think I could have done it. It was more a love letter to a certain time. Llanelli. It’s just that type of town, it’s a strange place – it inspires affection in us even though it’s a dead end in many ways.

Les Mun: It’s got very little going for it in some ways, but there are elements of it that are like James Joyce’s Dubliners, you know every character in every story is trying to escape from it, but some how they always end up coming back because there’s a pull. Because you grew up there, and for nostalgic reasons.

Matt Jones: I think at the time it just seemed right, it seemed like a good way to celebrate a place when you couldn’t meet or go out. So we just thought we’d celebrate. And get even more tapped into that sense of togetherness that we had. I think with some of our other stuff there’s sometimes a kind of cynicism, and a sarcasm, there’s some fairly satirical lyrics – especially when it comes to a commentary on the classism in this country, for instance. There’s a kind of socialist heartbeat throughout. I think that’s a recurring theme in the band.

Gary Raymond: And that’s in that’s in this album as well, isn’t it, really? It’s more other people’s stories, but that’s all still there. Because that was part of lockdown and a part of the pandemic the way people from different classes had to experience it.

Matt Jones: Oh, yeah, absolutely. So, you could have gone a number of routes, couldn’t you, you could have gone for like a frontal assault, you know, talking about the inner plight of the people, or there’s this approach that suits the band which is more oblique. That infuses these things with a sense of the slightly surreal, a sense of humour, and more than anything joy. It was one of those things, where you naturally go there when you write. It’s that question of, when you write, how much of your approach is instinctive? Because for me it’s always been instinctive. In retrospect I didn’t know that’s what we were doing but we were tapping into something at the time.

Gary Raymond: So how much has the experience of creating that album informed you as a band now? We’re in a new phase perhaps, but we’re obviously still experiencing the pandemic. We’re learning to live with is as the phrase goes.

Les Mun: Well, we’ve just released an album on Elefant Records in Spain. And a massive contribution was made by a singer Estella Rosa from Holland. You know, we’ve never personally met her. But she’s made a massive contribution to the album, fantastic singing voice and everything.

Andrew Clement: It probably wouldn’t have happened a few years ago, technologically it wouldn’t have been possible. And without the online social connections we got used to. Matt can explain better how it came about.

Matt Jones: Well, Estella she’s got her own blogging site where she does reviews, and she’s got her own label as well. But basically, the music that she’s into tends to be some of these sub-genres that I didn’t even know of before we connected. But it transpires that what she’s into is like retro-pop, sunshine-pop, sophisto-pop – those three things probably cover it. So Estella happened to hear Electric Lliedi Land and she was almost like dismayed because she considered herself such an authority on this area. She was saying to us, you know, almost in an accusatory way, Why didn’t I know about you?

Well, as you can tell we’re quite shy and retiring sorts and we haven’t done a very good job at all adapting to the 21stCentury. Anything like PR, we didn’t really bother with that at all. But we were being assisted at the time by a guy called Carl Morgan who did the artwork [for Electric Lliedi Land], who is an archivist and curator at Swansea Museum. And he was fantastic, he got us out on Instagram and said ‘do this, do that, do the other’ to create some buzz around it. So, from that Estella found us and was like, You should be doing so much more with this. So, she interviewed me. And we were being introduced to all this fantastic European Indie Pop. This was all happening, suddenly a Welsh band in touch with this international community. I said to Estella, you know, I’ll write us a duet. And it turned into 10 songs. She brought out things in our music that weren’t so obvious before. To top it all off, Estella said why don’t we go to Elefant records? This super Indie Spanish label. Next thing you know, we’ve got a record deal.

So what can I say? You know, it’s an amazing story. But it’s absolutely 100% genuinely the truth. One thing led to another led to another. And it all came about as a network of people connecting over work they genuinely love doing. That spirit of community started and expanded right across into Holland and so on. I think it’s never been better for us. And that’s a fact. I don’t think I’ve ever felt that sense of camaraderie and togetherness that came out of it, it was totally unplanned.

You can listen to more from The Hepburns on Soundcloud.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.