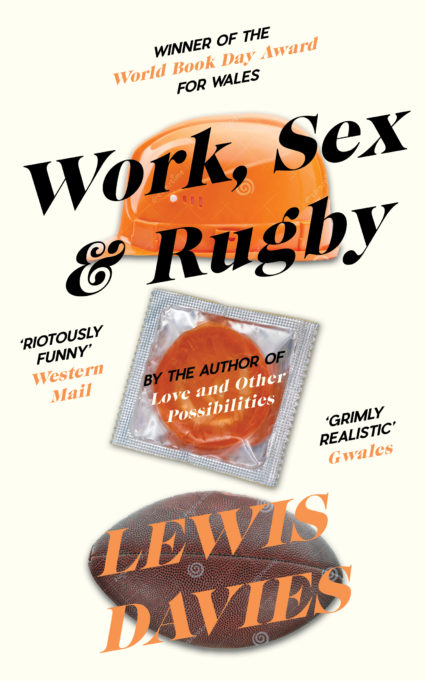

Whatever happened to the Welsh working-class novel? As Parthian Books prepares to publish a new series of reissues of key works of modern Welsh writing, Huw Lawrence writes about the first to come out, Lewis Davies’ nineties classic of disillusioned youth, Work, Sex and Rugby.

After 1979, industrial life in Britain became a shadow of what it had been and the working-class novel about solidarity and warm communities disappeared. Britain, within a globalised economy, now imported rather than manufactured her goods and what work remained was focused on the ‘service industries’, more menial and more scarce than before. A once-respected working class fragmented, its substantial lower end becoming the deprived subject of some of today’s more desolate novels. They do not describe confrontation and class differences but focus on hardship and the stigmatisation of the poor in an ever more unequal Britain. In 1988, Christopher Meredith’s post-industrial Shifts portrayed the end of Wales’ industrial era and the beginning of the bleak space that is left behind it. Work, Sex and Rugby was published five years later, but, although contemporary, it remains more in keeping with an earlier period, shining a light on workers as a class still here in south Wales, showing the repetitiousness of their lives and the warmth of their community. In this sense, it is maybe the last working-class novel.

If one wants to look for precedents, then the most likely are the ‘angry-young-man’ novels of the fifties, which portray a working-class no longer badly off materially but resentful of the repetitive drudgery that is the main condition of its existence. That’s exactly what Lewis Davies’ hero must come to terms with. “Surely there was something else”, he thinks. However, there is not, and he must come to terms with it. His ex-girlfriend, who stayed on at school, heads towards a different sphere of life.

This theme is developed through a simple, unobtrusive plot as we follow Lewis through a few days of his not very uplifting existence. He is out with a new girl when we first meet him, a sensible, working-class girl who seems more mature than Lewis, as tends to be the case at the age they are at. She is the kind who will be suitable for him henceforth, though we soon come to realise that the girl he wants is that first love who stayed on at school.

We see Lewis at home with his parents, where we are privy to a brief scene in which his father blames him for turning his back on education, which would have brought him choices. We see a lot of Lewis at work, where his employer points out that there is still pride and even pleasure in a job well done. Later, we see him playing rugby, and then out on a drunken rugby trip. His kindly employer understands the working-class reality that is dawning on him, having experienced the same realisation himself. We are shown enough of his employer’s history to realise that he had not been granted Lewis’ educational opportunities and that these are relatively new.

We remember that the book’s author is also named Lewis when on occasion he breaks with the third person, entering the story directly in the first person. It carries the message that Lewis Davies is closely involved. He did in fact work in an unskilled capacity in the building trade for not insignificant periods and belongs, or belonged, to the class he portrays. Obviously, this gives Work, Sex and Rugby its ring of truth and its range of realistic and colourful characters and is why their warm relationships come across so easily. The atmosphere and detail is unquestionably convincing. Swansea is recognisable. Dunvant always did have a male-voice choir of reputation. It all flows in an easy, down to earth style with south Wales coming out of its pores, keeping most of the meaning beneath the surface for the reader to pick up on.

There are no union activities or working-class movements providing either education or entertainment. Apart from sex and rugby, there is work and the pub, and sex is already getting stale for Lewis, and his enthusiasm for rugby is “slipping away”. It will leave only work . . . and the pub. Once, there were associations and clubs to absorb leisure and a wide variety of ‘non-vocational’ evening courses delivered at colleges for people’s benefit. The associations dwindled with de-industrialisation and the college courses got phased out by an educational ‘reform’ that wanted a measurable return from every course and saw no sense in improving the quality of life for its own sake. Although the reforms made the gap between the classes easier for some to cross, it was evident by the nineties that British society had become less generous in spirit.

In comparison with Lewis’ world, those earlier characters in those fifties’ ‘kitchen-sink novels’ seem to inhabit a lost utopia of full employment, when there existed credible political channels for class discontent. In that not very distant past it was possible to interpret your situation through the lens of another system, Marxism, whether you agreed with all of it or not. Although Lewis is ripe for greater political understanding, that route had been closed off by 1993, so Lewis just gets sadder and angrier, because for him there is no solution, not even in theory. He notes that even the religious drink. It is “so you can forget about last week and try to keep next week out of your head”. For ‘week’ read ‘life’, since the town “would absorb his energies for the next forty years”.

By the end of Work, Sex and Rugby, what divides him from the girl he loves – her name is Marianne – is not simply personal. It is obviously social as well. His reactions to her in their final meeting are emotional and angry. She is calmly on the move. Tellingly, she asks her angry and inchoate former lover: “Are you sure you don’t want to hit me as well?”. Their courtship has already ended. Now their acquaintanceship more or less ends too. “You’ll never leave this place or give up the job you hate so much” – “Perhaps I don’t want to Mar. Perhaps it was always you who wanted to leave”. Mobility is a feature of the middle class, the working class not so ready to leave the place where they were born and raised. The reader understands them both, an experience that moves his feelings beyond the characters to focus on the sad, insoluble class division. The door that education opened for Marianne is the door to another class.

Lewis is the one who will probably show the most consistency, for what that is worth, and it certainly is worth something. Her more refined new ‘self’ will slip now and again, probably depending on whom she is with, for the social ladder always speaks of ‘above’ and ‘beneath’, and she will have a foot in two camps from now on. Her natural companions will not be people born into either the middle class or the working class, but class-transferees like herself, and there are thousands, uncertain about ‘belonging’, firm nonetheless in their belief that things happen to people because of choices that they make. Lewis, firmly working class, is thus more fatalistic, placing emphasis on the power of external events rather than on individual will. His ex will go on pursuing her individual goals and valuing independence, things hard on his scale of values. He will benefit, without noticing it, from a close interdependence with his fellows. With a little luck, he will become resigned, like his employer.

Ironically (one hopes), Labour Minister John Prescott announced in 1997 that “we’re all middle class now”. Lewis and the rest of the working class must have laughed. They did exist, of course, and despite these degrading times they still do, living in warm communities where there is quick empathy and ready eye contact, and laughter, still almost as close-knit and slow to change as Work, Sex and Rugby portrays. Lewis will have come to appreciate its virtues by now.

It has been argued that the humane concessions granted by capitalism’s fear of communism, in the Cold War period, were quickly taken back again after the Soviet collapse. The process took place at the expense of those with the least. Today’s ‘gig’ economy with its zero-hour contracts has gone further again and makes Lewis look lucky. Today, low-paid, middle-class employees like nurses admit to having used food banks, and supermarket bins get raided after dark. The truth is that the world of Work, Sex and Rugby has been overtaken by worsening times. All the more reason to reprint it, then, a marker identifying a spreading social quicksand caused by political failure to address people’s basic needs. Let it also be an appeal to other writers that it’s time to speak out.

Lewis Davies

Work, Sex and Rugby by Lewis Davies is available now from Parthian.

Huw Lawrence is a contributor at Wales Arts Review.