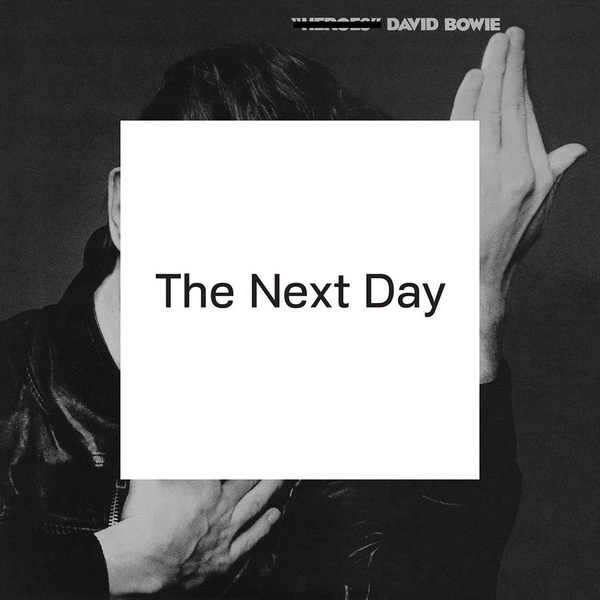

Gray Taylor casts a critical eye over David Bowie’s new album The Next Day, his first studio album since 2003’s Reality.

In the Beatles’s motion picture début, A Hard Days Night, during a staged press conference, Ringo is asked if he’s a mod or a rocker? He replies that he’s a mocker. Should David Bowie be asked the same question the answer would be such a strange and unpronounceable portmanteau that I don’t even dare to attempt it. Needless to say that Bowie, in his fifty year recording career, has leaped about genres synthesizing (or stealing, depending on if you’re a fan or not) and revolutionising the idea and concept of the rock star.

From 1970 to 1980, Bowie reinvented himself and the potential for white British rock stars to explore creative depths previously seen as off limits. Then came 1981. 1982. 1983 – the biggest album of Bowie’s career – Let’s Dance. 1984 – the worst album – Tonight. 1985 – dancing with Mick Jagger. 1986 – Muppets. 1987 – Never Let Me Down – shit. 1988 – Glass Spider Tour – shame about the spider. Bowie had sold out. Traded invention for world-wide stardom and musical manipulator for musical money maker. By 1989, he was in a band called Tin Machine and they released an album that Q magazine gave a rapturous four star review and then, along with every other journalist, spent the next twenty years slagging off.

The nineties were an easier decade, for fans and rock writers alike, to enjoy and recommend Bowie’s music. Slowly Bowie clawed his way back to some sort of cutting edge artist with a model wife on the cover of OK magazine. 1995’s Outside had moments that genuinely thrilled and some moments about art murder bollocks that went absolutely nowhere. The hard rock meets drum ‘n’ bass experiments of Earthling were vital and alive but still covered in Tin Machine guitarist Reeves Gabrels’s horrific screeching guitar, a sound that could only be described as akin to a room full of parrots having their heads twisted off.

Bowie completed the nineties like almost every other rock musician; completely bored with himself. So bored in fact that, on the 1999 album ‘Hours…’, he decided to take on the role of an everyday bloke reminiscing regretfully about unfulfilled teenage love affairs. The Thin White Duke doesn’t get the girl?! Fuck off, basically.

To be fair, I’m a huge Bowie fan, and all of Bowie’s nineties output held some joy for me; ‘Jump They Say’ (1993’s Black Tie White Noise), ‘The Motel’ (Outside), ‘Little Wonder’ (Earthling), ‘New Angels Of Promise’ (‘Hours…’), were all slices of classic Bowie. But none held as much joy as 1993’s Buddha Of Suburbia, a non-soundtrack to the TV adaption of Hanif Kureishi’s novel. Here, Bowie remembered, maybe due to the nostalgia of the book, why we loved him in the first place. Ziggy-style nasal vocals and in-joke warbles aimed at Bolan. The experimental soundscapes of Low and “Heroes” were back. Mike Garson’s unmistakable and irreplaceable piano from Aladdin Sane.

We remembered that Bowie had taught us about outsiders, different sexualities, worlds we’d never experienced, and time wanking and falling on the floor. (How I wished the latter had been better explained so I hadn’t asked my mum what it meant). It was clear much of this was down to the inspiration and personnel Bowie was dealing with. One person who didn’t feature in Buddha’s line-up, but had always brought something special to Bowie’s work, was producer Tony Visconti.

Visconti has been involved in some of the greatest and some of the strangest rock music of all time. A Brooklyn-born Anglophile who understands instinctively the creative process and, hence, has helped great artists realise their greatest works. Bowie is no exception; The Man Who Sold The World, Diamond Dogs, Young Americans, Low, “Heroes”, Lodger and Scary Monsters, all benefited from Visconti’s presence in one way or another. After 1980’s Scary Monsters, Visconti was not asked back to produce 1983’s Let’s Dance and a sort of fey Glam Rock cold war began between producer and artist.

So, much of Bowie’s output subsequently missed Visconti’s presence until, in 2002, he returned for Bowie’s return-to-form album, Heathen. A truly great album with great Bowie songs on it and great performances too. It was followed rapidly by 2003’s not-quite-as-good but still alright Reality album. It seemed as if we had David Bowie back at the top of his game. Then, after a triumphant world tour, a lollipop stick hit him in the eye and he suffered a massive heart attack. Well, something like that; either way, Bowie disappeared. I imagine, since Bowie is now an astute business man, that his exile was as much to do with the bottom falling out of the record industry. Not much point in risking life, limb and eyes by releasing an album of new material when everyone will download it for free, is there?

Then, on the eve of Dai Bobby Jones’s sixty-sixth birthday, David Bowie was reborn. Without warning, a new single with accompanying video appeared. ‘Where Are We Now?’ appeared slight at first, maudlin and bruised, reminiscing, it seemed, of grand old days hopping round Berlin with Iggy Pop. Slowly, it’s affecting whimsy got under the skin of the listener. The song was never going to win over Bowie detractors, but fans were happy and expected the following album to be some kind of gentle trip down memory lane. A bit like Scott Walker’s shit mid-seventies covers albums but nice all the same.

What a different album than that expected The Next Day truly is. When you listen to it, you realise that the releasing of ‘Where Are We Now?’ as the first single was pure Bowie-staging rock drama. Sort of his 1973 retirement in reverse. The music on the new album is certainly career reflective but in such a joyous way that even its more questionable nature seems like genius.

Take the title track, which opens the album; the very first thing that comes to mind is that Bowie is using his ‘one of the lads’ rock voice from the dreaded Tin Machine days. But hang on, it sounds right, the tune is good but mainly the vocal sounds right, the guitars tearing a path for Bowie to stride confrontationally back into our conscious. It immediately makes you wonder how good the two Tin Machine albums could have been with more suitable musicianship and Visconti’s presence as producer. So far, okay, but if a Tin Machine album follows this, I’m going to be pissed off. I needn’t have worried as the album continues with one of it’s finest tracks. ‘Dirty Boys’ starts with a strange honking saxophone and abstract guitar.

Automatically, you’re not only roaming the streets with Bowie and Iggy, but you’re thrown into the world of Iggy’s classic Bowie-produced album The Idiot. We’re ‘living on a lonely road’ skulking, coke-nosed, hanging with some shady characters. Fear is our weapon, fear and a fantastic, uplifting, classic chorus. And then, like the opening track, in a few and a half minutes, those dirty, dancing big boys are gone.

by David Bowie

The Next Day is full of concise pop and rock music; nothing outstays its welcome and the majority demand immediate repeat listens. The second single follows: ‘The Stars Are Out Tonight’. It’s the same rock song Bowie’s been writing since the ‘Hours…‘ album. Nothing wrong with that, but I feel strangely disconnected from the listening experience. Perhaps this feeling is due to the strange lyric in which megastar Bowie sets himself amongst us mere mortals to gaze critically at, among others, ‘Kate and Brad’. Much better is ‘Love is Lost’, which is, at first, a bit reminiscent of the eighties, you think. No, hang on, it’s a bit like the early eighties. Then, the track builds and the backing vocals build and, fuck me, it could’ve come straight off Bowie’s most underrated album, Lodger. It’s Bowie on top form, vocally, musically and lyrically. ‘You’re a beautiful girl, say hello to the lunatic men’, Bowie sings and at once you’re in classic territory, back amongst all those madmen. ‘Where Are We Now?’ comes next and now makes perfect sense, already an elder statesman of a Bowie song, sent into chill-down proceedings after the four reckless rockers that have so far been ruling the sound. It truly is a beautiful song.

‘Valentine’s Day’ is sure to be a fan favourite because it is slightly reminiscent, if you squint your ears, of Aladdin Sane-era Glam pop. However, I would argue that it’s slightly too much like his mid-eighties period, especially with its lightweight backing vocals. Nice enough though. Oh Christ, as if Bowie can hear me thinking, the next track recalls Bowie’s energetic drum ‘n’ bass period. Scared? Well, perhaps you should be, but ‘If You Can See Me’ is actually a very strange song that would have been par for Bowie’s course in the late seventies. Strangely infectious and with some odd vocal effects, you’re reminded once again of Lodger. Tremendous abstract fun.

‘I’d Rather Be High’ begins with a catchy guitar riff but, worryingly, seems to be harking back to Never Let Me Down‘s social conscience lyrics. Then you realise that Bowie is playing a role: that of a seventeen year old soldier. Warning! Bowie geek observation approaching. The vocal line of this song is straight off one of Bowie’s earliest compositions, ‘When I’m Five’, which remained unreleased for many years but was released in the eighties when the ‘Love You Till Tuesday’ promo film from 1968 was issued. Is this Bowie testing us hardcore fans? When he was seventeen playing five he used this vocal harmony, now at sixty-six playing seventeen it reappears. Here might be the key to this album; looking back, looking forward, looking back again. This is Bowie taking us through everything we knew or thought we knew about him and twisting it sweetly and simply in a modern context.

‘Boss Of Me’ follows and is actually quite a likeable track, albeit with a fairly throwaway lyric. Now, if those funny boys in the Flight Of The Conchords were to do another Bowie parody they would probably call it ‘Dancing Out In Space’, but he’s done it himself. It’s a great fun track and it almost sorts out the damage done in the eighties where he would almost write pop classics but screw them up somewhere along the line. Again, had Visconti produced ‘Blue Jean’, ‘Loving The Alien’ or ‘Time Will Crawl’, they could’ve been real classics.

The best track for me up next: ‘How Does The Grass Grow?’ The verses are classic Bowie writing, slightly off-centre but making perfect sense, notes between notes, and then all of a sudden he’s la-ing The Shadows’s ‘Apache’ in the chorus. It’s an astounding effect and almost the perfect Bowie song; strange but catchy, obtuse but familiar and welcoming. If that weren’t enough, this great song also incorporates Bowie’s classic deep croon in a marvellous middle eight where he sings ‘I gaze in defeat’, yet sounds as triumphant as he ever has.

‘(You Will) Set The World On Fire’, the hardest rocker on the album, explodes into life and contains some truly impressive guitar work from Bowie’s long-serving guitarist, Earl Slick.

‘You Feel So Lonely You Could Die’ is a classic Bowie ballad, drawn from the same vein as ‘Rock N Roll Suicide’ and sounding strangely like it should be closing the Rocky Horror Picture Show (a good thing). ‘I can see you as a corpse, hanging from a beam’, sings Bowie chillingly, and if you weren’t chilled enough, the actual end of ‘Rock N Roll Suicide’ pops in to say a friendly ‘hello’. Stunning.

Perhaps that’s where this fantastic album should’ve finished, because up finally is ‘Heat’ which, if you haven’t heard any of Scott Walker’s music since 1978, might sound quite odd and interesting. Unfortunately, I have heard all of that music, and Bowie is just a different songwriter and can’t do the spare, one word sentence-style lyrics that have helped enhance Walker’s enigma. And, although the track is clearly indebted to 1978’s ‘The Electrician’ – amongst other Walker greats – it actually comes off more like that song from Labyrinth when he’s running up and down the stairs of an Escher painting come to life. Saying that, maybe such a nod to Bowie’s hero is a perfect end to an album that, like Scary Monsters, looks back upon the previous decade(s) and synthesizes what it sees into a perfect, fresh new future. There are some extra tracks on a special edition, but really they are for the hardcore faithful, although I can imagine that a Q writer will rush to tell you how great ‘I’ll Take You There’ is and that it should’ve been the first single. Probably the same writer who gave Tin Machine four stars.

The Next Day is a classic David Bowie album. It’s eclectic, commercial, sometimes obtuse and strange, sometimes straightforward and likeable, but always, like all of Bowie’s best work, completely engaging, interesting and occasionally enlightening. The musicianship, production and Bowie’s voice are perfectly in synch, with each complementing the other throughout. Powerful and charismatic as ever, sixty-six year-old David Bowie might well have made 2013’s greatest album and the finest comeback imaginable.