Dylan Moore reviews a well-timed production of The Devil Inside Him, John Osborne’s first play, directed by Elen Bowman at The New Theatre in Cardiff.

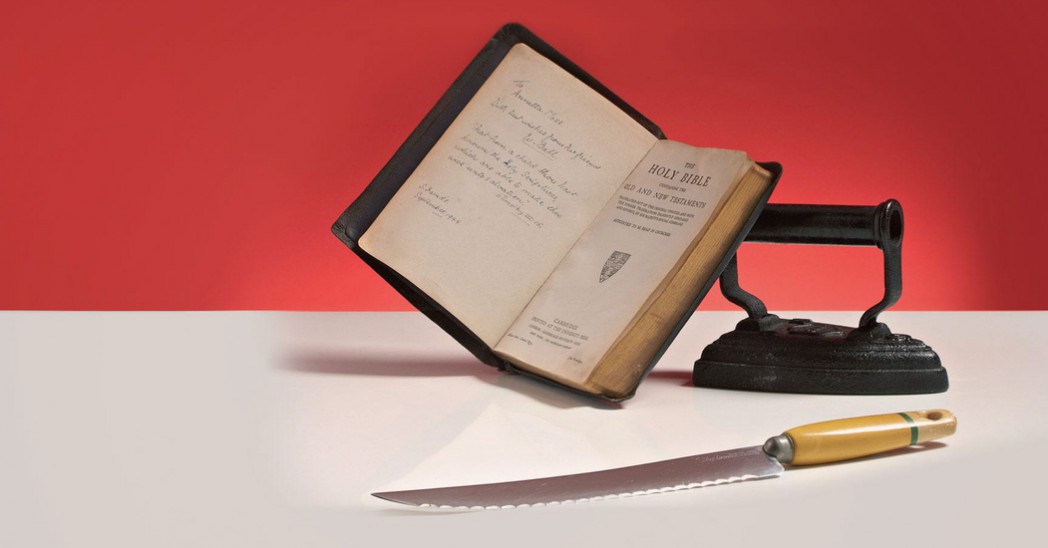

8 May 1956, the opening night of John Osborne’s ground-breaking Look Back in Anger at the Royal Court theatre, has attained a quasi-mythical status in modern British theatre history. The audience was shocked by the sight of an ironing board onstage; the play ruffled establishment feathers, challenged a moribund post-war Britain; the Angry Young Man was born. National Theatre Wales may well have planned their schedule so as to produce The Devil Inside Him to coincide with the anniversary of that famous date, but they certainly could not have foreseen that the second week of May would also be the week of a historic hung parliament, frantic coalition talks and the end of thirteen years of New Labour. As the curtain rose in Cardiff, Gordon Brown’s prime ministerial car made its final journey to Buckingham Palace; by the interval, David Cameron had already accepted the Queen’s invitation to form a new government.

Cameron comes to power promising to cut the deficit and mend Britain’s ‘broken society’, conservative code for a perceived epidemic of teenage pregnancies amongst working class girls and a new jobless generation of ‘angry young men’. More than anything else, what Osborne’s play proves – through the microcosm of a ‘respectable’ household in a small Welsh village – is that the tensions between austerity, morality and the human spirit are nothing new.

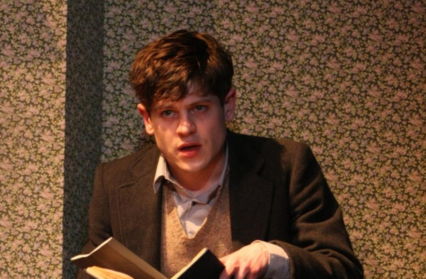

Huw Prosser, portrayed here in a talismanic central performance by Iwan Rheon, will inevitably be seen as a proto Jimmy Porter. His creator’s name will always be synonymous with his most famous play and, to an even greater extent, the glib journalistic label ‘Angry Young Man’. But in significant ways, Prosser is more than that. He foreshadows the rise of the teenager that was to come in subsequent decades. His body language and behaviour seem somehow anachronistic, typical of the modern, sullen youths demonised by later generations – the kind identified by sociologist Stanley Cohen in his classic study of mods and rockers, Folk Devils and Moral Panics. Certainly, ‘the devil inside him’ is a ‘folk devil’; if it exists at all, it has been planted there by others. Prosser is the archetypal individual who refuses to be constrained by society. There are plenty of archetypes here, as you might expect from an eighteen-year-old playwright: Huw’s overbearing father and sympathetic mother; the dogmatic, judgmental local minister; the garrulous Mrs Evans, a ‘daily woman’ who provides much needed comic relief from a sometimes unbearably angst-ridden examination of relations between good and evil, body and soul.

The production is the most traditional of those in National Theatre Wales’ first year programme, and Cardiff’s New Theatre by far the most traditional venue. The stage set itself is the apotheosis of kitchen sink drama, a perfectly realist rendering of a comfortable dining room and sitting room, Welsh dresser stacked with blue and white plates and topped by two china dogs. The attention to period detail in the furnishings, wallpaper and skirting boards would lend the play an aura of cosiness – lamps lit, curtains drawn – if it were not for the animalistic intensity of Rheon’s performance. Huw Prosser prowls the stage like a caged animal, alternating between outbursts of nervous energy and periods of sullen introspection. The contrast between the actor’s often vicious language and the comfortable setting is at the heart of the feeling of constriction that Osborne’s script aims at, and director Elen Bowman must take considerable credit for making this a successful and, for the most part, smooth production of what is a passionate and interesting but occasionally flawed script.

There are moments, inevitably, where the rawness of Osborne’s writing comes through: ‘What is it you want?’ asks Dilys, the Prossers’ servant girl at the heart of the play’s tragic twist; ‘A little beauty in an ugly world,’ says Huw, guilty of writing poetry described by his father and Mr Gruffuydd, the minister, as ‘vile filth’. ‘The way of the flesh is the way of weakness,’ Mr Prosser contends, warning his son against ‘damn fool impulses.’ Diagnosing him variously as ‘possessed’ or ‘mad’ or ‘wicked’ or ‘soft in the head’ – a lovely example of Osborne’s early immersion in south Wales – the other characters all seek to label Huw, sometimes physically surrounding him while he holds his head in enraged frustration.

Osborne recounts his experiences of Wales – his mother was Welsh – in his autobiography. On the evidence of this play, you feel he must have experienced those stifling aspects of mid twentieth century valleys’ life occupied not with religion but with sin. The outside world is represented by the impression of a colourless day of wind and rain, the view through the window a single leafless tree. The sterility indoors is hardly alleviated and the intense realism of the set creates a claustrophobic atmosphere, a perfect way of emphasizing Huw’s aliveness in the face of the dead world that surrounds him. It is telling that when people leave the household it is to deal with a death or sing at a chapel choir festival on a makeshift stage made of coffin lids. This is recounted humorously but the implication is clear: this is a society far too concerned with the next life to be bothered looking after the weak and vulnerable in this. Even at this tender age, Osborne’s anger was impeccably directed; the censors didn’t pull the play for nothing, and NTW would not have been able to stage this production had not the sole surviving dog-eared copy turned up in the Lord Chamberlain’s archive in 2008. Despite the existentialist debate at the dinner table, it is left to the ironic wisdom of Mrs Evans to deliver the sucker punch where religion is concerned: ‘You can’t be religious all the time, can you?’

Religion is not the only focus of Osborne’s ire. The play is ahead of its time in many ways. If, understandably, it fails to anticipate the proliferation of children born ‘out of wedlock’ – it is strangely moving to hear the stigma that comes with this debated in an accent belonging to the area which now has the highest teenage pregnancy rate in Europe – it certainly offers a sympathetic portrayal. This is a play that seeks to understand rather than condemn. It rails against the lack of compassion shown by the church and is startlingly modern in its exposure of misogyny: fear and hatred of women run through the bone marrow of the community, from the painted statues of the Virgin in the Catholic church to the deeply unsettling language (Mr Burns: ‘I don’t know why they don’t eat their babies like an angry bitch eats its pups’). This is challenged powerfully in the final scene when Helen Griffin, playing Mrs Prosser, draws a huge gasp of approval from the twenty-first century audience as she delivers a telling rebuke to her overbearing, uncomprehending husband: ‘I am your wife, but I am still myself.’

Language becomes more important as the play goes on. As Osborne warms to his theme, his protagonist grows in eloquence. His elemental, animalistic grunts subside into terrible beauty when we discover his ‘very rare and precious gift’. Prosser is a poet. ‘Words are wonderful, lovely things,’ he says, ‘we all have the seeds of poetry in us… but only a few ever blossom, only a few in a hundred years.’ The crucial plot twist elevates Prosser from a Holden Caulfield figure – confused young man teetering on the brink of insanity – to a kind of Mersault, from Albert Camus’ The Outsider, a man who, having broken the ultimate societal taboos, finds a new kind of freedom. Barely articulate at the start of the play, the closing act finds Prosser discovering a sudden verbal eloquence which breaks through the rehearsed arguments of both religion and science. He too rebukes his father – ‘You have been interrupting me my whole life’ – before ascending the stairs in a memorable and thought-provoking finale.

If the new coalition government really wants to mend what it perceives as ‘Broken Britain’, it would do well to begin by listening to the Huw Prossers of the world, the tens of thousands of angry young men – and women – who have been interrupted their whole lives too, painted as folk devils and condemned to life as yet another jobless generation. After all, as this play contends, ‘people are human, even in a Welsh village.’

Dylan Moore has written a number of reviews for Wales Arts Review.