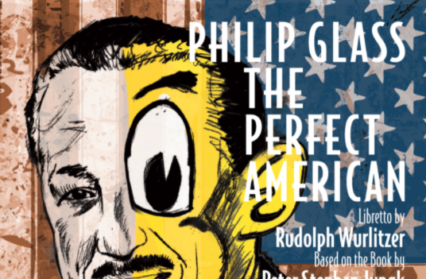

Cath Barton reviews The Perfect American, an opera made up of two acts composed by Philip Glass with the English National Opera.

Towards the end of The Perfect American (in repertory at ENO until 28 June) the assembled cast sing of:

‘Disneyland, where dreams come true and tomorrow is only a miracle away’.

The music sounds as if it is leading to a big climax, but stops several repeats short of getting there, to be followed by a short scene in which the undertaker tells Walt Disney’s disaffected employee, Dantine, that Walt’s family have had his body cremated rather than cryogenically preserved as he had made them promise. The chorus continues singing, but offstage, as an echo. The anti-climax may be what Philip Glass wanted. After all, in real life dreams come true only unpredictably and miracles rarely happen.

Neither Disneyland nor the world of opera is like real life, and neither do we want them to be. We go to them to escape the drabness of everyday life, to see everything heightened, for the bright lights and the loud music.

Of course it isn’t all about loud singing, definitely not. For me the most pleasing and memorable experiences of opera (I cannot speak for Disneyland!) are when everything comes together in a unified clarity of purpose and execution. The Perfect American is by design episodic and in some of the episodes my senses were overwhelmed by the complexity of the images – the projections of trains and wheeling gantries are over-busy and the music is in many of these scenes incidental, as in a film. Those who tend to regard Philip Glass’s music as mind-numbingly boring should be pleasantly surprised by the variety in this score, but it is mostly of passing interest, rather than contributing to a coherent whole.

In the tableaux with members of Walt’s family and the full chorus, the music is stronger, more in the vein of Glass’s Songs from Liquid Days (1986), but always stops short of a big climax. There is, as Glass said at the Hay Festival in May, ‘always some music’ and as he doesn’t seem to have to struggle to write it, my feeling is that he is perhaps content with that music being good enough, rather than working on it to make it as good as it could be.

The Perfect American is an enjoyable curiosity rather than a significant addition to the repertoire of contemporary opera. I’m not sure that it could be re-staged in the future anyway, as Philip Glass wrote the music to go not only with the libretto (by his friend Rudy Wurlitzer, based on a novel by Peter Stephan Jungk) but also the designs by Dan Potra. On the night I saw the production at The Coliseum, 200 people in the audience were there under ENO’s Undressed scheme which is aimed at attracting new audiences to opera. I think that the spectacle and, in some scenes, magic of this production will certainly have encouraged some of those people to return for more, to go and see ENO’s upcoming production of The Magic Flute, for example, which like The Perfect American is being produced in collaboration with a theatre director.

The collaboration between Philip Glass, Dan Potra and director Phelim McDermott has definitely been a fertile one. The involvement in this production of McDermott’s theatre company, Improbable, and its Skills Ensemble of dancers brought a freshness to the action which, for all its singing prowess, the ENO chorus could not have a achieved alone. Singing the role of Walt Disney, baritone Christopher Purves was exceptional, brimming with vocal energy, his every word clear. It is time WNO engaged him to sing again in Wales, where he has previously received acclaim for the title role in Wozzeck (2009) and as Beckmesser in Die Meistersinger (2010). Amongst the rest of a solid cast, soprano Rosie Lomas stood out in the dual roles of Lucy and Josh, and I hope we will see and hear her too in Wales in the near future.

The way in which the dancers of the Improbable Skills Ensemble’s focused attention on the principal singers was nowhere better done than in the scenes with the animatronic Abraham Lincoln and Andy Warhol – played beautifully by bass Zachary James and tenor John Easterlin respectively. These scenes, which flanked the interval and so were at the centre of the production if not its dramatic heart, remain in my mind for their clear and clean choreography and dramatic integrity. And, wonderfully in the Andy Warhol scene, humour! And Philip Glass’s music? Well, it was an essential part of the whole. So it did its job.

Cath Barton is an English writer who lives in Wales. Her prize-winning debut novella The Plankton Collector is published by New Welsh Review under their Rarebyte imprint. She is a frequent contributor to Wales Arts Review.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.