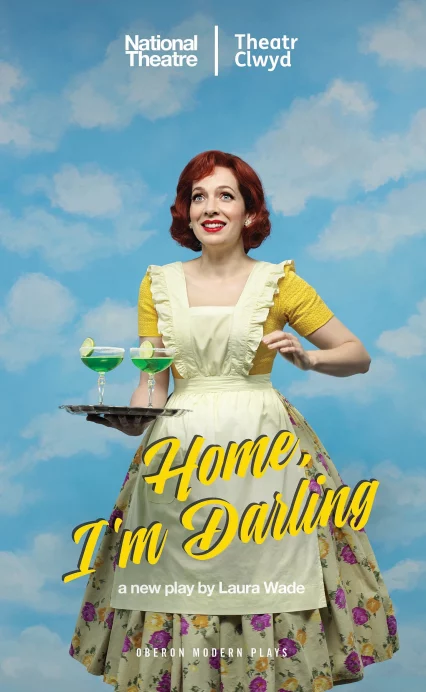

In 2018, one new Welsh play rose above all others in exploring some of the most pertinent feminist issues of our day. Emily Garside explores the political message of Laura Wade’s Olivier Award-winning comedy Home, I’m Darling.

‘You’re wasting yourself when you could choose not to,’ says Sylvia to Judy. Sylvia is, without doubt, the character who talks the most sense in Laura Wade’s award-winning satire Home, I’m Darling. The mother of Judy, who is living what Sylvia calls a ‘cartoon’ of a 1950s life, having dropped out of the working world to be a housewife, Sylvia despairs of her daughter’s choice. But should we as feminists support Judy’s choice? Or is the dark secret of many a 30-something that actually there’s bits of Judy’s ‘cartoon 1950s life’ that looks quite enviable?

Sylvia reminds Judy that this is not what previous generations fought for. And that’s the conflict as a 30-something woman watching Home, I’m Darling. Every feminist instinct sides us with Sylvia, puts us shoulder-to-shoulder with her as she shouts at Judy that she’s wasting her life as she flits about the house in her Doris Day get-up. But there’s a side of me that also empathises, even envies Judy’s choice. Her position. (And yes, ok, her wardrobe).

So, let’s start with that wardrobe. It’s tempting to be po-faced about this and cry ‘it’s not about the frocks but…’, to sidestep the enviable wardrobe Katherine Parkinson’s character has in the play. And yet, surely freedom to wear pretty dresses is part of the point – if that’s what women want to do. Of course, Judy takes it to an extreme, while I pair my 50s frocks (of which I have many) with Converse or boots, hers is the whole hog – stockings and tights and all. Which feels, appropriately, more a male fantasy or a play costume than ‘real’ clothes. Of course, for Judy it’s an illusion, as Sylvia reminds her that in the 1950s these outfits were impractical, no fun, and bloody freezing in the winter. Women fought for ‘better’ choices. But of course, Judy has chosen those clothes, and even if she does go to the extreme, if it makes her feel better about herself and her life then it is unequivocally the unfeminist thing to do to criticise that.

Like everything a woman wears, even today, it’s a costume signifying something else. Something she wants us to think of her, rather than something she is. But how much do we as women do that every day still? How much of an effort do I make to be sure to be ‘feminine’ in my dress to counteract my short hair? How many times has a colleague commented on my ‘short’ skirt or whether I wear trousers in the last year? Suddenly the 50s frocks don’t seem quite so anachronistic.

Like everything a woman wears, even today, it’s a costume signifying something else. Something she wants us to think of her, rather than something she is. But how much do we as women do that every day still? How much of an effort do I make to be sure to be ‘feminine’ in my dress to counteract my short hair? How many times has a colleague commented on my ‘short’ skirt or whether I wear trousers in the last year? Suddenly the 50s frocks don’t seem quite so anachronistic.

Though as much as I like a frock it seems an awful waste to just use them to clean the house in. And that’s the crux of the contemporary battle in Home, I’m Darling: that just of being ‘just in the house’, of taking care of the home. Why is this a ‘waste’?

It would be a different discussion if Wade had given Judy children. A woman who chooses to stay home or not with her children of course faces challenges (as director Tamara Harvey documented in her #WorkingMum thread during rehearsals). But Wade’s decision not to give Judy children is a powerful one. Sylvia’s comment, ‘If you had children, I’d understand it’ encompasses much – it is acceptable for a woman to stop, to drop out of a career, stay at home, if and only if she has children. Because despite generations of feminism, the sad truth is no woman is judged more harshly by other women than on her decisions relating to children.

Who, in climbing, sliding down, or clinging to the rockface that is career progression, hasn’t thought ‘I wish I could stop?’ Because it is hard for women, still. From being paid less, being promoted less, working harder to get less. To the engrained sexism, overt sexism, sexual harassment. ‘Dropping out’ altogether must be tempting for so many. But the idea of wanting to ‘drop out’ makes me feel like (more) of a failure of a woman – not managing, not coping with having it all.

Judy has the dubious benefit of immersing herself in a bubble, and has cut herself off from the outside modern world almost entirely. That is, I confess the one element of Judy’s choice I can’t wrap my head around. As much as many of us would like to silence the 24-hour news cycle occasionally, there’s a sense of the power in the access to information, and the powerlessness of a woman without it. The idea that there’s still so much to shout about, fight for, makes ‘dropping out’ of society actually the element I pass judgement on Judy for the most. Feminism is exercising choice yes, supporting choice. But it’s also continuing the fight. And you can’t do that if you cut yourself off from the world.

It is perhaps Judy’s isolation from the world that makes the ‘Me Too’ moment the crux of the play. Feeling a little out of step, a little out of date, with how women are speaking of these issues, with how we are now challenging men, when Judy finds herself receiving, and then pandering to, Marcus’ sexual exploits, it’s a troubling double-edge sword. It is that moment in the play that shows the cracks in what Judy’s life is, or has become; she is a broken woman clinging onto some kind of identity.

It is clear by the end of the play that Judy’s world is one born out of her own mental health conditions. And that is Wade’s central, ultimate message: that mental health is a feminist issue. The pressures on women in this modern world to be everything at once are incessant – the pressure to maintain a blossoming career and a perfect home, the pressure to be both in control of our sexuality and to cater to the male gaze. In Wade’s beautifully written, at times hilarious, and always charming, play, Judy’s need to slip into a different time is born of some deeper issues. And the only feminist reaction is to want her to get better.

But also, I want desperately to support Judy’s right to stay at home and clean. To dress up in a time capsule wardrobe. And there’s elements of her life – the single car family, walking to the shops, the waste free, cook-from-scratch lifestyle – that actually is desirable, admirable, even fashionable, now.

I look at the play and see in principle, as a feminist, I should support Judy’s right to choose. But like Sylvia, I can’t quite reconcile that with the fact I want Judy to fulfil her potential, to be everything she could be. Sylvia is hiding from a world that has beaten her down once too often, and every woman watching it will understand that. And it should be okay to ‘do a Judy’ sometimes, for a bit, and retreat. Wade’s play speaks of that desire in all of us. But we must dust ourselves off and re-emerge, be ‘brave and strong and better’, and we must do that together, support each other, including the Judy’s of this world who may need our help rather than our criticism or condemnation. Because we’re not done marching yet, and we can do it in frocks if we want.

Emily Garside is a writer, an active member of the Cardiff theatre community, and a contributor to Wales Arts Review.

(Home, I’m Darling image credits: Manuel Harlan)