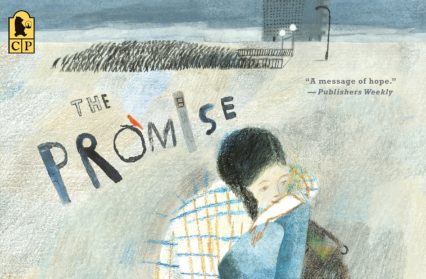

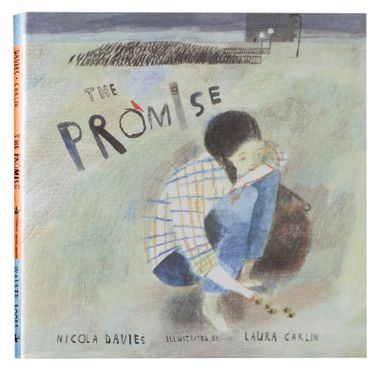

Nicola Davies gives unique insight into the making of children’s environmental book, The Promise, and its journey from print to a new BBC film set for release in October.

There is a piece of advice that I’ve heard imparted by many writers and critics, especially when it comes to writing for children. It is that you must not write with an agenda. I confess that every single one of more than sixty books that I have written for children, has a very definite agenda. Broadly speaking, my agenda is to inspire deeper connection with the natural world for all my readers, but especially those children who are not experiencing a happy childhood. The natural world has been my greatest comfort throughout my life. It has kept me turning outwards with curiosity and delight when sadness and trauma threatened to fold me inwards, away from the light. I feel passionately that the disconnect with nature that humankind has experienced over the last decades, is the root of our profoundest problems at a global level and at a personal one. So, with my writing I want to help to retune our value system, to respect the network of life that supports us: this is how we can heal our planet and our souls.

I’ve written all sorts of things, fiction, narrative nonfiction, poetry, long things and short. But my favourite medium is the picture book. For those of you who have left children’s literature behind, or feel that you have ( just FYI, you haven’t, because all the books your read and were read to you are part of who you are), healing of planets and souls may seem like rather a big ask for a text with just a few hundred words. But the words in picture books are pared down in the same way that a poem is; every word multitasks, every phase is streamlined, the whole text choreographed to deliver a sequence of ideas, images and emotions that bring the reader along the narrative line to its conclusion.

The words of course don’t work alone. The interaction between words and pictures is a magical, alchemical phenomenon, very similar to the way lyrics and melody work in a song. When I write a picture book text it’s my job to leave enough space for that magic to happen. There must be enough room between the words for the illustrator to walk about, and tell the story they want to tell. If I write a text well enough, their story and mine will serve the same end. For me, the very best outcome is for an illustrator to show me something I never imagined or saw was there in the words.

Picture books are an extraordinary and underrated art form, they can deliver the biggest messages, across all boundaries of age, gender, and culture. When I began to write and be published I always said I would rather write a picture book beloved of a generation than win the Booker. That’s still true and although I haven’t got a Gruffalo or a Guess How Much I love You to my name I do have The Promise.

Almost a decade ago now I was asked by my editor to write a picture book version of the famous novella The Man Who Planted Trees. Originally published it French, this story outlined the transformation of a barren landscape by the quiet tree planting of one man and captured the zeitgeist of the growing environmental movement of the 1950s. I knew the story very well, but being a writer for children and having just completed a book about climate change, I wanted to write something that would speak to younger readers most of whom are, inevitably, in urban environments. I was also motivated by the research I had read about the impact of trees in cities, creating cooler, moister micro climates as well as having a huge positive impact on human mental health.

Almost a decade ago now I was asked by my editor to write a picture book version of the famous novella The Man Who Planted Trees. Originally published it French, this story outlined the transformation of a barren landscape by the quiet tree planting of one man and captured the zeitgeist of the growing environmental movement of the 1950s. I knew the story very well, but being a writer for children and having just completed a book about climate change, I wanted to write something that would speak to younger readers most of whom are, inevitably, in urban environments. I was also motivated by the research I had read about the impact of trees in cities, creating cooler, moister micro climates as well as having a huge positive impact on human mental health.

I don’t know how I thought of the street child as my story’s protagonist. I don’t know why I gave her no name and implied that she was just one in a long line of planters, passing on their task of greening cities across generations and continents. All I know is that one day I sat down at my desk and two hours later I had the text of The Promise.

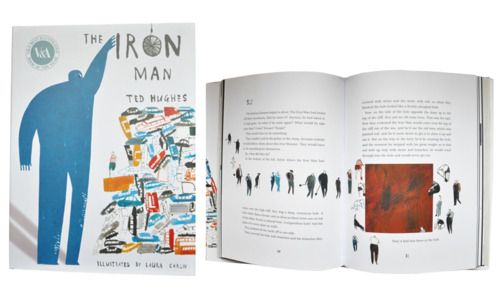

The choice of illustrator was just as intuitive. I saw Laura Carlin’s extraordinary work for Ted Hughes’ The Iron Man and knew that her way of defining space and how humans move within it was the absolute key to the visual storytelling The Promise needed. When the book was published in 2013 I knew we had created something really wonderful, something world changingly powerful. But there was no launch and no fanfares. And the world did not change as I had hoped.

But this is where I needed to remember my own words, written in the voice of the acorn planting heroine of The Promise:

Nothing changed at first

The gritty wind still scratched the parched cracked streets

The people scowled and scuttled to their homes like cockroaches

But slowly slowly slowly

Shoots of green began to show.

The first shoot of green for me was an e-mail, from a woman who was working in Afghanistan in areas ravaged by long years of conflict and disruption. She was, she told me, helping to establish community gardens where people could grow food and find peace and healing. Copies of The Promise were being passed from hand to hand around the country, like sacred contraband, giving inspiration, hope and validation.

The next few shoots came on school visits. Pre-Covid they were a mainstay of my working life. When you look out at an audience of kids in a school hall, even if that hall is in a very expensive kind of school, you can spot the children who are not thriving. And it was these children who responded most to my reading of The Promise. A child in Boston who came into my session with three minders and moved around on hands and knees, told me that the story was ‘about him’. A little girl in upstate New York, from a family of six who were living in a car, and whose teacher had never seen her smile in four years in school, stood listening to the story with a beaming grin. A child from a very expensive west coast academy thanked me for the story that was helping her through her parents war zone divorce.

There wasn’t much attention in the UK, but the New York Times listed us as one of its top ten of the year (I sat shaking in a cafe in Montreal with the pages of the paper in front of me). There was a gradual trickle of foreign editions; every European language, South American Spanish, Japanese, Korean and Chinese (though sadly, not Welsh). I sometimes met editors at literary festivals and book fairs abroad who would shake my hand and thank me for The Promise, but it’s so hard to know what a book is really doing, once it’s out there in the wild.

I went on writing books. Lots of them. But The Promise was always the one I turned to when I wanted to show what I was really about. I consoled myself: the story was out there in the world, working. Teachers and children would send me letters, stories, artwork inspired by it, or post their responses to our book on social media. So even if I felt discouraged by the fact that my publisher had let the beautiful hardback edition go out of print, paperback copies were still available and people still seemed to want to use them.

Out of the blue there was another big green shoot. A film director called Chi Thai wanted to make an animated film version for a BBC environmental film slot. She was the perfect person to make the film, not just immensely skilled and creative, but she got what the book was trying to do, she got what Laura and I had created. All three of us were on the same wavelength from the moment we first met.

Out of the blue there was another big green shoot. A film director called Chi Thai wanted to make an animated film version for a BBC environmental film slot. She was the perfect person to make the film, not just immensely skilled and creative, but she got what the book was trying to do, she got what Laura and I had created. All three of us were on the same wavelength from the moment we first met.

The BBC commission was confirmed and Chi could start work in earnest on the film. I told myself not to get excited. It was lovely, but it would probably go up on the BBC website and be forgotten. Just as no-one in the mainstream had really seen the magical value of the book, I felt that Chi’s film, no matter how wonderful, would suffer the same fate of always being on the sidelines.

In truth, I think I had lost faith in the power of my story and its ability to deliver its green message. So when Chi and I were invited to take part in Climate Story Lab, a coalition of organisations and individuals who work to support the very best communication about the climate crisis, I was skeptical. I went with Chi to the conference in London, sure I would feel out of place with so many amazing and experienced documentary makers, most of whom were young enough to be my children. But when our turn came to present our film, I was asked to read The Promise aloud. I was really nervous, but I’ve read those words so many times. I let them take me and I watched as they broke in the room like a wave. The response was incredible, the audience understood that the story of The Promise was a climate change fable that asked people to change and change now.

At the end of the conference, thanks to CSL we had secured funding from the Children’s Investment Fund Foundation for an impact campaign to back up the film. I’d never heard of an impact campaign before that week but here’s what it is: if you make a film that you want to effect change in the world the impact campaign is what does it. It allows viewers to translate what they felt when they watched your film, into action.

Chi, Laura and I have an organisation, Wild Labs, who are putting together our impact campaign. The idea is that children, schools, families and communities make Promises for the Planet, that the organisations with which we partner can help them deliver. They may for instance want to make a promise to establish a school garden, and we can partner them with an organisation ready to offer help and funding for that. They may want to promise to save an area of biodiverse rainforest, so we can pair them with a conservation organisation like The World Land Trust. Or they may simply want to plant a tree, and we can make that happen too.

Promises run both ways, both making and keeping, so part of The Promise impact campaign will encourage people to ask political leaders to keep their promises on climate change and the environment: I Promise, Promise Me.

We want our viewers to engage with this story, we want them to take its meanings into their hearts. So when they’ve watched the film, we want them to take time to read the book, to absorb it and reflect on it, because for Chi Laura and I it’s the message that matters. We’re trying to make copies available to the children who need them most, not just the existing audience of already eco minded schools and families. Walker Books, the publisher of The Promise, has offered us three thousand copies at a crazy discount. We want these to go to children in the most deprived urban areas.

We want our viewers to engage with this story, we want them to take its meanings into their hearts. So when they’ve watched the film, we want them to take time to read the book, to absorb it and reflect on it, because for Chi Laura and I it’s the message that matters. We’re trying to make copies available to the children who need them most, not just the existing audience of already eco minded schools and families. Walker Books, the publisher of The Promise, has offered us three thousand copies at a crazy discount. We want these to go to children in the most deprived urban areas.

In October, The Promise film will be available on BBC online. At time of writing we don’t know if it will get an airing on other BBC platforms. We hope so. The more people who view it online the greater the chances of that happening. We have big ambitions for our film. We’d like the campaign to go global to involve people in a world wide community of Promisers, who embrace the message that, through promising to change ourselves, we can change the world and demand that our leaders make and keep promises to address the climate emergency.

The problems we face with the aftermath of COVID, social inequality and climate change, are so many, so varied and so huge. To solve them we are going to have to be more creative than we have ever been. Stories and the imaginative thinking they foster have an important role to play there. But perhaps the most important job that stories can do is to show us the simple difference between right and wrong. Stories can show the one change we need to make from which all others flow, so that mending our planet and changing the world can seem as simple as planting an acorn.

View the trailer and sign-up to watch The Promise when it is released on the the 16th of October.

You might also like…

Tom Bowman discusses the concepts behind his new book, What if Solving the Climate Crisis is Simple? and asks us to flip the picture of the climate crisis upside down and revaluate our roles in establishing the future we hope to see.

Nicola Davies is an award-winning author, whose many books for children include A First Book of Nature, Ice Bear, Big Blue Whale, Dolphin Baby, Bat Loves the Night and the Silver Street Farm series. She graduated in zoology, studied whales and bats and then worked for the BBC Natural History Unit. Nicola lives in Abergavenny, Wales