Jamie Woods was at the Rhys Davies Short Story Conference at Swansea University for an event dedicated to one of Wales’ best prose-writers.

Opening with a piece of work-in-progress theatre, and closing with musical metaphors, The Rhys Davies Short Story Conference proved as eclectic and enigmatic as the literary form it sought to explore. This symposium was clearly programmed with a narrative in mind. Themes of identity, belonging and place, and the ideas of otherness and of outsiders ran through the debates and discussions, and propelled the weekend from a starting place somewhere between Chekhov and The Rhondda, into the contemporary, postmodern literary landscape. Readers familiar with the short story will be aware of the turn: the moment in the story where events or actions are skewed, even slightly or subtly, in order to create conflict or crisis. The turning point on the Saturday afternoon focused on the writer Will Self. Reading and talking about his work, he showcased his humour and literary talent, and for the fifteen-minute break afterwards, there was an engaged optimism around the conference. Self then appeared as part of a panel discussing the provocative question ‘How relevant is the short story in 2013’, and in doing so he went from being the hero of the conference to antagonistic villain.

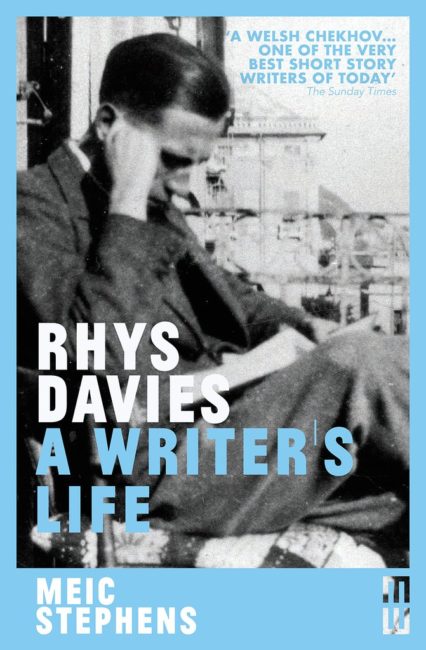

But to open, some scene setting: the first night was devoted to Rhys Davies, the prolific and revered Rhondda-born writer, who died in 1978. Meic Stephens introduced his new biography of Davies – Rhys Davies: A Writer’s Life (Parthian Books) – and provided the audience with a character sketch of one of Wales’ finest authors. Davies wrote over a hundred short-stories, along with numerous novels and other works, many of which draw from his own experiences; but in his own autobiography he remained cryptic and secretive, protective of his personal life, even shaving years from his age. He wrote of a Wales from which he was an exile, having moved to London at twenty. He wrote of a society from which he was adrift, a gay man at a time when homosexuality was a criminal offence. His deserved place in the Welsh canon will be cemented with his work prominent in the Library of Wales’ forthcoming Stories anthologies.

D.J. Britton’s play Silverglass was a bold and energetic piece of theatre. The concept of mirrors suggested by the title was used from the outset – opening with the dapper Rhys Davies (played by Richard Elfyn) and the sophisticated novelist Anna Kavan (Eiry Thomas) dressing themselves in preparation for an evening. A fictionalised take on the friendship between the seemingly unlikely paring of Davies and Kavan, the play offered a vignette of the time they spent together, incorporating incidents and discussions from their lives into a single ‘remembered’ evening, with Davies stepping out of the play from time-to-time, addressing the events in the past tense. In a brave and effective technique, Britton’s script utilised both writers’ works to illustrate not only Davies and Kavan’s differing literary output, but to tell versions of and to mirror their biographical stories.Davies’ comedic style, his light, reflective touch, and his ability to look into worlds from the outside was demonstrated with the inclusion of his story ‘The Benefit Concert’, which was read with both characters taking turns to narrate and act out the scenes. The minimalist set worked wonderfully here: Kavan’s chaise longue doubling as a hospital bed, and Davies’ legendary trunk substituting for a lectern. Kavan, a heroin addict, wrote much darker work, and Eiry Thomas’s delivery of it was frenetic and harrowing. Both actors worked hard throughout, and that a pilot run-through of a play could be so well-received and smooth is testament to their performances.

Friday night’s introduction to Rhys Davies led neatly onto the first panel of the conference on Saturday morning: Rhys Davies and the Welsh Short Story. Dai Smith and Tony Brown set out an historic framework in which to place the Welsh short story, with contemporary colour and ideas of creative process provided by acclaimed short story writer, novelist and playwright Rachel Trezise. Smith suggested that Welsh short stories are ‘windows into the Welsh experience’ and ‘live epiphanies’, reflecting the isolation, detachment and insecurity of life in rural Wales, the post-industrialised landscape, collectivity and community, national identity, and, certainly with Trezise’s latest collection, immigration. While our neighbours in England have lost interest in the format, and collections of Welsh Writing in English are missing from schools, Smith suggests that in Wales, writers have looked to America, with Ron Berry taking on the influence of Henry Miller, and Rachel Trezise adding that when she started out ‘I thought I was the first person to come from the Rhondda and write’. In Wales the short story tells us the news, the situation, however ephemeral, and it must therefore remain a key part of our cultural environment.

Tessa Hadley, a writer who teaches at Bath Spa University and whose short fiction regularly appears in The New Yorker, led a creative writing class. Hadley spoke about the importance of structure in the story, in particular the importance of endings, and the inclusion of a moral judgement. A benefit of the short story over the novel is the ability to share an entire work in a public reading. A complete short story can be read out, leaving an audience with a resonance of meaning; as opposed to a few pages of a novel, where they might be left with an impression of prose style and little else. Hadley quoted Joyce’s ‘The Dead’ to reinforce her belief that the key to a short story ending is ‘all in the aesthetic, the cadences’.

‘A story, to be lasting, must be grounded in time and in place, but rich.’ Edna O’Brien addressed the conference, in conversation with journalist Alex Clark, and her talk was filled with so many wonderful bon mots on creativity and the art of the short story. ‘It must be satisfying and dynamic, like a revolver. The novel is a machine gun, but there’s nothing wrong with a revolver’. The Irish author said she finds truth in the short story, ‘ultimately the feelings and longings and secrets of the human soul. There’s not a single lie in Chekhov’. This rings true with the earlier panel’s notion of the short story as news. And her lack of books while growing up echoed the panel’s desire to expand and improve school syllabuses, which she identifies as being ‘a serious issue, with a huge reward’. ‘If we were to stop reading, really reading, if that were to cease for any reason, people would be much poorer’.

The weekend’s star turn was up next. A degree of trepidation awaited Will Self, both amongst anxious long-term fans and among those whose only knowledge of him stems from his droll and cynical appearances on Question Time. He dispelled any concern quickly, with an erudite and witty take on the short story, riffing on the idea from Marshall McLuhan’s Understanding Media that photo-illustrated news has replaced the function that the short story once held. However, a short story can be something magical, ‘like shards of sunlight: sharp when good, illuminating when it’s up there with the best of them.’ He then showed this in practice, with a reading of his story ‘The Minor Character’. A satire on the dinner-party set in London, he read it with aplomb, performing it, rather than just reading it. Steeped in irony and ending with a meta-literary joke, the story seemed to go down well. And although some in the audience made it clear in the Q and A that they didn’t like the sociopathic tendancies of the author, or the rhetorical repetition of character’s names (the sublime Bettina Haussman, and good ol’ Phil Szabo drinking champagne), the mood seemed set for a positive panel session to follow.

Where we’d left off, Self was clearly quite positive and taken by the short story. He’d not written one in a while, perhaps he’d start writing them again. But in the panel discussing the relevance of the short story in 2013, he suggested nothing could be further from the truth. He declared the short story to be a bracket, a word count, not a platonic form. The high-spot of the short story was in the inter-war period. Now though, he believes ‘the connection between words and money is insecure. Lots of people are publishing stuff on the internet, but it can’t make any money. You can’t be online and read, you can’t sustain the moment’. Self went on to state that the web bores him, that publishers are ‘Oxford-educated people who work at Prontaprint’, before delivering a rant about Google and Amazon and the tailoring of knowledge. ‘Do you want me to do “wither” now?’ he asked the chairman, Wales Arts Review’s Gary Raymond. ‘I don’t know what’s going to happen. It’s not clear who the readers will be. I’m not sure of young people’s involvement, their capacity for sustained attention.’ ‘It doesn’t mean that people aren’t going to write them, but it’s not as mainstream as it was.’

This is where Self’s arguments break down. He is the most mainstream person speaking at the conference, the most high profile and central to the London literary establishment. Through talent and timing he exists in a world where being a writer is a reasonably lucrative business, and for him to see the short story or the internet as boring or irrelevant is different to how the majority of other working writers see the subjects. On the panel with him were Alex Clark, and authors Claire Keegan and Cynan Jones. They talked about the joy of the short story, the art and structure of it – Clark spoke of the ‘immediate sense of being arrested’ and Jones praised the economy of the form. Clark responded to the Raymond’s prompting of the Kindle Short as a new format for delivering shorter work, saying she likes the ability for authors to write a one-off story and publish it easily, comparing the cheap downloads to a Penguin Short. Keegan maintained the outlook for the short story is far from gloomy, pointing out the ability to access so much work cheaply or freely on the internet: ‘I grew up in a house without books. I find access to literature startlingly positive. I have no qualms if people want to read my work on screen or on paper’, and citing that she discovered many older short story collections by downloading them.

Self found himself talking about piracy, and the death of the publisher, akin to the way people spoke about record labels following the birth of the MP3. Perhaps the real impact the internet will make on fiction will be the accessibility of the short story. Although there isn’t necessarily a lot of money floating around, the rise of online journals, self-publishing and reading apps show that there is a market, there is a readership out there, and the scaremongering that the whole thing is about to implode isn’t far from luddism. Self-published authors will be at a disadvantage compared to traditionally-published authors due to marketing budgets, the need to hold down a day-job due to a lack of an advance, and the editing and proofing process. But advances certainly aren’t what they used to be, and editing and proof-reading services exist. Just because there is less money, and it is less mainstream, doesn’t mean that all is despair for the short story.

Sunday’s events were more subdued: a coda of repeated themes and ideas. Locating Literature looked at place with Claire Keegan, Jon Gower and Shena Mackay. This triumvirate of Celts talked of how ‘time and place allow fiction to happen’ (Keegan), ‘We don’t lose memories of places, if we just draw on them’ (Mackay), and the art of the ‘innate storyteller’ (Gower). Again, we saw outsiders, and a lack of belonging. Mackay, a Scot, feels influenced by her home country, but writes looking back, in exile. Gower stressed how much he would love to live in the countryside again, and writes of places he once lived, away from people. Keegan surmised her writing practise and how she is able to create such lasting work: ‘I write what the story needs. Not so interested in writing about the high-tech or the modern. But water, air, remain. The things I write about haven’t actually gone away.’

The final session saw Gower and Mackay joined by Cynan Jones in The Long and Short Of It – a panel discussing the differences between writing short stories and novels. Mackay quoted Edward Albee’s remark that ‘all my plays are full length: they’re full to their length’. Jones followed that diktat with his short novel The Long Dry, and particularly when he cut two-thirds of the word count from his new novel The Dig. Jones noted that ‘if 2000 words of a 2,500 word short story are just wonderful prose, then all you’ve got is wonderful prose, no story, muscularity or propulsion.’ Gower agreed that for the perfect story you should be able to see ‘every sentence doing its work’. Another music metaphor, this time from the room, that the short story is to the novel is as the single is to the album: an introduction to the artist, accessible and consumable. Gower replied succinctly: ‘hookline, structure, if you deconstruct it it’s a Motown single’.

Across the weekend the short story emerged as an enigmatic literary form: structured yet loose; poetic yet didactic; past its heyday and increasingly unmarketable and yet vibrant, vital, and important. Conceived with a deep intake of breath and written with a burst of energy, the format is clearly alive and well, if not monetarily then artistically. Its natural brevity suits the modern age of short commutes and MTV generation attention spans, the internet providing a fantastic outlet and resource for this work to exist on. Jon Gower, in summing up, declared that short stories represented ‘companions, brief illumination, here are our characters, they are like you’: mirrors and peepholes and news broadcasts from outsiders, exiles, readers around the world.

The Rhys Davies Short Story Conference, Swansea University, 13-15th September 2013.

Recommended for you:

After the recent successes of the third Cardiff Book Festival, Kelly Keegan asks why, with all the best intentions, the efforts of the modern book festival to be inclusive and relevant still fall short.