240pp, The Borough Press, £14.99

The American West of the nineteenth century, as much a myth as a time and a place.

The American West of the nineteenth century, as much a myth as a time and a place.

‘What is a boy to do out in the west?’, Tom Walker’s aunt asks when the youngster’s father says that he’s taking his son out on the road. Become a man, that is what a boy is to do out West. The West is where men are tough and of few words. At least, that’s what our books and our films tell us.

The western genre has long had its strict conventions: the taciturn wanderer, drinking by campfire, saloon card-games, a showdown, revenge, redemption. And filmmakers and novelists have long played around with these ideas, attempting to refashion and update this most classic – and most conservative – of genres. Patrick deWitt’s novel The Sister Brothers and The Coen Brothers’ film adaptation of Charles Portis’s 1968 novel True Grit are two successful recent examples of this.

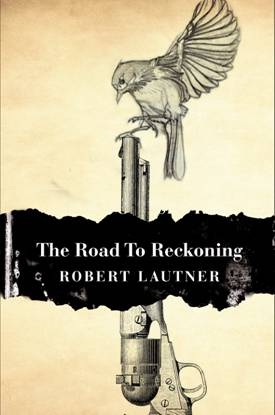

Robert Lautner’s impressive western The Road to Reckoning adds to the list of works that are both steeped in their genre while also being at one remove from it.

For one break from the norm, Tom Walker, his father and this story never actually get to ‘the West’. And this is 1837, decades earlier than most current representations of classic western mythology.

The novel opens as Tom Walker’s father, a spectacles salesman, hits on an opportunity to make some money away from depression-hit New York. Father and son head out towards the shifting frontier selling Samuel Colt’s new ‘Improved Revolving Gun’. ‘The Lord made men. But Sam Colt made them equal’, as the saying goes, which, while far from true, nicely gets across the potency of the invention.

Tom Walker narrates The Road to Reckoning in the first-person, looking back on the trip he took with his father forty years earlier. ‘I, to this day, hold to only one truth: if a man chooses to carry a gun he will get shot. My father agreed to carry twelve’, Tom tells us. From that, you might correctly gather that son is soon left all alone, out in the wilds, far from safety.

Twelve-year-old Tom’s saviour comes in the shape of ranger turned bounty-hunter Henry Stands, ‘a good bad man’ and ‘a man of few friends’. Our western hero, a man who has ‘no time for women, even in their own houses’.

Interestingly, Lautner draws Tom not as a young man out to get personal revenge on his father’s killer, but as a young man who wants to get back to his aunt and family home. In similar style to True Grit, The Road to Reckoning follows the odd couple as they cross the land. Companionship and arguments follow. They seek out people, and people seek out them. And, whether he was looking to or not, young Tom gets his chance to right some wrongs. It is a fairly slim plot, which places emphasis on the novel’s characterisation and setting. In truth, the couple’s relationship isn’t as well-drawn as one might hope. Neither character fully comes to life. However, there are impressive scenes – both gritty and tender – involving the two. In particular, a scene in which it becomes apparent that, not only is Tom looking for a father-figure, but Henry is looking for a surrogate son, is deftly handled.

Lautner – an Englishman who, the biographical note tells us, ‘lives on the Pembrokeshire coast in a wooden cabin’ – smartly paints a picture of the changing country around his tale of the two adventurers.

‘The canals made friends of strangers. Then the railroad came and people got in a right big hurry,’ Tom remarks. And he later tells us of the melancholy sight of the abandoned wagons that litter the plains: ‘The skeletons of settlers’ hopes and dreams.’

But it is the dark shadow of the Colt that hovers over every page of the book. This works well.

The Colt is the killing tool that, along with its successors, would help to shape America. This is the gun that led to the death of Tom’s father. ‘intelligence and reasoning has gone from the art of loading a gun, which once took patience and practice. Now drunks believe themselves badmen and shootists’, the adult and world weary Tom tells us, in one of his many hard-earned pearls of wisdom. Lautner uses this matter-of-fact, clipped style – perhaps reminiscent of the speech of the time – throughout the book.

The narrative’s framing device of a middle-aged Tom looking back on his boyhood trip – being able to recall conversations word-for-word and actions in minute detail – is awkwardly handled. For much of the novel, he simply describes the events of his trip, without offering much in the way of personal reflection on them. We learn too little about Tom’s life after the events of his formative journey. Old Tom Walker’s voice doesn’t fully connect with the story of his childhood.

There are hints at how this might have worked better. Tom regularly expresses his forty-year-old shame at not offering his father greater protection in his moment of need. And, in a neat observation from Lautner, Tom talks of his regret in not being strong enough to move his dead father to a suitable place of rest. ‘Maybe I am writing this to be a boy again’, Tom says at one point, and one wishes this relationship between the old narrator and his younger self had been fleshed out.

Lautner could also have gone further in tinkering with the genre’s conventions. ‘I left that part of the Appalachians having never crossed them. The west still a mystery and you can keep it’, Tom says at one point, which gets across something of the book’s, and the narrator’s, interesting ambivalence to the western myths. However, the novel still repeats, and heavily relies on, these same glorified and well-worn stories.

Overall though, Robert Lautner (a pseudonym, by the way – is he a fan of Twilight‘s leading actors?!) is to be applauded for a more than solid novel. The Road to Reckoning captures an interesting age of change in America. And it does so in a nicely just off-centre style of western, with its unusual setting and pre-teen protagonist to the fore.