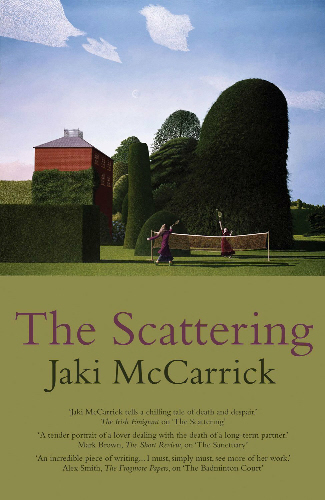

Crossing the border from the Irish Republic to visit friends in Northern Ireland at the turn of the century, I expected to find that the frontier itself would be a terrifying place, a land of watch towers, armoured cars and check points. After all, this was only six years after the IRA ceasefire, a time when the peace process was still finely balanced and when Bill Clinton’s visit to Northern Ireland (referenced by Jaki McCarrick in a particularly affecting story) was something of a pivotal moment. Perhaps irrationally, I locked my doors. I needn’t have bothered. Apart from the return of familiar British road signs and the unfamiliar bedecking of kerb stones in red, white and blue, I found myself passing through a quiet landscape, something McCarrick characterises here as the ‘gloom of the border with its secret paths and its neglected farms’. From the driver’s seat, it did not seem a place made for dramatic incident but over the range of short stories contained in The Scattering, McCarrick identifies in these borderlands ‘what was hidden’ and sees their ‘numinous potential’.

Crossing the border from the Irish Republic to visit friends in Northern Ireland at the turn of the century, I expected to find that the frontier itself would be a terrifying place, a land of watch towers, armoured cars and check points. After all, this was only six years after the IRA ceasefire, a time when the peace process was still finely balanced and when Bill Clinton’s visit to Northern Ireland (referenced by Jaki McCarrick in a particularly affecting story) was something of a pivotal moment. Perhaps irrationally, I locked my doors. I needn’t have bothered. Apart from the return of familiar British road signs and the unfamiliar bedecking of kerb stones in red, white and blue, I found myself passing through a quiet landscape, something McCarrick characterises here as the ‘gloom of the border with its secret paths and its neglected farms’. From the driver’s seat, it did not seem a place made for dramatic incident but over the range of short stories contained in The Scattering, McCarrick identifies in these borderlands ‘what was hidden’ and sees their ‘numinous potential’.

McCarrick herself hails from Dundalk, the border town that has seen more than its fair share of terror during The Troubles. The Troubles themselves inevitably provide a background to many (but certainly not all) of the stories in this powerful collection. Indeed, it is the sense of inhabiting a border that really shapes the structural and emotional topography of The Scattering. There are the familiar borders that one might expect in such a collection, such as those that exist between exiles and returnees, incomers and ‘natives’. However, these borders are often revealed to be porous and open to subversion. As one character says in the wonderful story ‘1975’, ‘Irish culture is alive and well and living in Birmingham’. We also find that McCarrick maps borders which snake their way along other fault lines, such as those existing between old and young, urban and rural, male and female, between divided notions of the self and between life and death. Indeed, this last frontier can be seen as McCarrick makes cross border raids on gothic horror and science fiction. But more of that later.

The Scattering has received a great deal of justified praise, much of which focuses on some particularly powerful stories in the collection. Returning exiles provide the focus for a number of them. ‘In the Black Field’ charts the romanticism of Angel, a returnee who has ‘not yet lost his city-born infatuation with green fields’ and who imagines that ‘the land communicated with him’. One can see McCarrick’s fine sense of the ironic as it is this exile who, in trying to embrace the land of his childhood summers, classifies one local as having a ‘desperate and cold ambition’, just as the returning exile in a later story imagines ‘how preoccupied and standoffish the people here were’. Indeed, when we first meet Angel, he is busily attempting to erect a fence around his rehabilitated old house; at the same time, a wall seems to have been erected between himself and his family.

The two linked (but not consecutive) pieces, ‘1975’ and ‘1976’ similarly reveal the long shadow cast by a personal history but this one is entwined with the tortured political history of the Irish borderlands. The former, in particular, is especially powerful in its depiction of the immediate disorientating aftermath of a terrorist atrocity: ‘A woman’s black, feathered hat and one black glove lay in a pool of bubble-topped grey water, swirling in a pothole.’ The family in these stories has been fractured, frontiers of mutual incomprehension being built up between father and daughter. Indeed, ‘1975’ itself is structured around the memories that return to a widowed father watching his daughter on the opposite side of a busy road as she waits for the bus back to London. Such incomprehension has an interesting counterpart in ‘1976’, which is told from the viewpoint of his daughter and who does not fully understand the seismic disturbances being felt elsewhere in her family. The final tectonic shift into adult knowledge and disillusionment is evoked in a beautifully understated way: ‘Shortly after I found the camera, I would stop calling my father Dada, call him Dad instead, a word that would always feel awkward and blunt in my mouth’.

Shifting identities seem to shape stories elsewhere in the collection. ‘The Congo’, for instance, is a tale of the narrator’s childhood relationship with a local kingpin, Devlin, and his gang. This is the antagonist who we are led to believe has ruined our narrator’s life when he tempted him to cross over from his privileged life in the local middle classes of ‘The Avenue’ and into the estates of ‘The Grange’. However, our perceptions of the protagonist and antagonist’s identities are subverted. Devlin is himself is described as ‘the overlapping of two people in one’ while the narrator talks of his ‘old self’ and his ‘London self’. When we find out who the perpetrator of an appallingly violent crime against the landlord of The Congo pub actually is, we wonder if we have in fact made a journey into the narrator’s own personal heart of darkness.

The identity or status of the narrator is again examined in the story ‘The Tribe’. It is here that McCarrick makes an expedition into the hinterlands of science fiction and it was here that she almost lost me. In fact, I had the same dubious feeling that I get when a ‘mainstream writer’ is found trespassing in territory that is not their native ground. There is even a reference to mankind resembling a virus, which sounds as if it was inspired by a certain Hollywood sci-fi blockbuster. I take it all back. Just as we wonder who the protagonist and antagonist are in ‘The Congo’, we might wonder who is the more threatening presence in the ‘icy Eden’ depicted in this story. Is it the ‘antler-headed male’ who brings savagery to the Ice Age Mesopotamian tribe of the story? Or is it the narrator from the Hell of a devastated future who brings the technology of destruction into a more innocent world via his apple shaped time machine?

There are other explorations of divided selves in stories such as ‘Blood’, which further illustrate how McCarrick is certainly not squeamish about making forays into other genres such as horror (and which also show off her teasing wit – I loved the idea of Dracula’s descendants being alive and well in the Cooley Mountains). The delightfully named central character, Fred Plunkett, discovers his hidden vampiric identity here, a ‘blood memory’ hitherto suppressed and brought to life. Another story, ‘The Stonemason’s Wife’ is itself a story of suppressed identity and sexual secrets – very personal borders – within a seemingly conventional marriage. Here, the strong male presence of a husband, Thomas L’Estrange, literally makes his wife’s world strange as she discovers both his transvestism and her own aroused reaction to it.

The collection ends with ‘The Jailbird’, an engrossing tale of a dominated stay at home son, a ‘Norman Bates [who] is alive and well and living in Castlemoyne’. The matriarch, Connie, is a beautifully drawn character and the story itself illustrates McCarrick’s fine ear for dialogue and her gift for describing the sort of suffocating familial relationships on show here and elsewhere.

The Scattering is a very wide-ranging collection that delineates the borders which shape and warp the lives of its characters. In doing so, it freely crosses and re-crosses those borders, playfully riffing off the notions that the idea of boundaries might suggest. The stories themselves violate the frontiers between genres and even break the borders between themselves, with characters and ideas appearing and reappearing in many guises. Those quiet borderlands that I drove through obviously have hidden depths, like ‘The Lagoon’ mentioned in one disturbing shorter piece in the collection. It is a strange, estranging, destabilising place and McCarrick picks her way through its complicated geography with the sure-footedness of a native.