Dr. Geraint Rhys Whittaker reflects on the ways in which The Swansea Troublemakers Festival is ‘An Artistic Experiment To Discover How a Place Can Be Re-imagined’.

How we develop an idea about a place depends on many factors. From what we’ve been told about it by others, to what we have learned through our own experiences and memories, we slowly develop a picture of what we think that place represents. This will change from person to person depending on who we are. Our class, race, gender, sexuality, nationality, religion, physical and mental capabilities, will all influence how we construct our own personal maps of what certain places mean to us.

The experience of walking down a street will vary from person to person, depending on how we use such places. For someone from the LGBT community, a street with LGBT friendly bars and cafes might be perceived as a place of solace, protection and acceptance, whereas for others it might be a place they simply pass by. How we therefore give life to a street, will change depending on what we derive from it personally and how often we re-visit these places both physically and emotionally.

The Troublemakers Festival, held on Swansea’s High street between the 13th and 16th of July was devised to encourage exactly this; for the people of Swansea to re-interpret how they think about and use the street, by using the arts as a catalyst to provoke new ways of interaction with the place.

It is the product of an ongoing collaboration between the Coastal Housing Group (a non-for-profit industrial and provident society formed in 2008 after a merger between Swansea Housing Association and Dewi Sant housing association) and Volcano Theatre company, both situated in the middle of the High Street. The cornerstone project of their partnership, The Troublemakers’ Festival was organised to encourage further interest in an area which has for too long been neglected.

I met Carrie Rhys-Davies, one of the organisers of the project team, before the festival began, at the Volcano Theatre to discuss this further. What used to be an Iceland supermarket is now their headquarters. Where once lay cereal boxes, provocative art pieces now stand, including enormous floating papier-mâché pigs which we sit next to, to discuss the festival. The building has come to symbolise the possibilities of change on the street, and from the beginning of our conversation, it’s clear to see that changing perceptions about the area was an ongoing priority for the organisers.

As Carrie enthusiastically shares, ‘We want people to come back and think of it as somewhere that is welcoming rather than somewhere you just pass through’.

As Carrie alludes, the High street has for too long become a place that many people pass through quickly. This was certainly the case for me as a teenager growing up in the 2000s with little in the street to keep me there, other than a personal fascination with neglected buildings.

The first street visitors see once leaving Swansea Central Train Station, for decades it has been allowed to deteriorate whilst other areas of the city such as the marina have developed rapidly.

For such an important street, it has always had a continuously challenging past. The train station was opened in 1850 and was central to making the street thrive as a crucial financial, artistic and cultural area of the city.

The Palace Theatre, now currently derelict, in its heyday hosted the likes of Charlie Chaplain and was where Anthony Hopkins gave his first professional stage performance. The Elysium Building, also now derelict, was once a cinema, ballroom and club for the town’s working men. The street was also home to many popular hotels such as the Cameron and the Bush, and was the location of the studios of Artist and Photographer, Henry Chapman, who was one of the first commercial photographers in the city.

However, whilst the street continued to be a hive of artistic creativity, the surrounding areas struggled with poverty and was referred to as ‘Little Ireland’ due to the amount of slum dwellings and the lack of toilets. This dichotomous relationship, between opportunity and poverty, is something the street has never been able to shake off.

The three night blitz of February 1941 hit Swansea hard, destroying 112, 000 buildings including many on the High street, and from the 1950’s onwards it further declined and remained a street of continuous contradictions.

It became home to Wales’s first gay club but also became a street synonymous with crime, homelessness and drug use, and with the building of the Quadrant Shopping centre in 1979 to the south west of the city, trade moved further away from the Street, contributing towards its further neglect and emptiness.

Over the past 5 years however, things have begun to change as the creative industries are moving back to the High Street allowing it to re-define itself. Led by Coastal Housing, Volcano Theatre and the increasing presence of artists at the Elysium Gallery, older buildings have been replaced by a tech and creative hub, and the re-location of South Wales Evening Post suggests that the street’s transformation continues.

The Troublemakers’ Festival is a continuation of this process. A range of events were scheduled from Thursday till Sunday to provoke as well as inspire, from meeting artists resident on the street, to film screenings, theatre performances, art workshops and inspirational talks. The street was also closed on Saturday and Sunday, to re-imagine how it could look like if it was pedestrianised.

Unfortunately, the abysmal weather on Saturday meant that many of the planned street activities were either cancelled or didn’t have the desired effect because the footfall was absent. This did not stop the die-hards getting involved in drum workshops in the rain or partaking in painting a wall with their own graffiti. Fortunately, by Sunday, the weather cleared up which allowed a makeshift skate park to be erected and the street came to life.

Unfortunately, the abysmal weather on Saturday meant that many of the planned street activities were either cancelled or didn’t have the desired effect because the footfall was absent. This did not stop the die-hards getting involved in drum workshops in the rain or partaking in painting a wall with their own graffiti. Fortunately, by Sunday, the weather cleared up which allowed a makeshift skate park to be erected and the street came to life.

This gave a taste of how the street could look and be utilised differently, and seeing it bustling with activity was a highlight. The powers that be should not underestimate how such an action as pedestrianising the area could really benefit the street and give it a unique buzz that nowhere else in the city has.

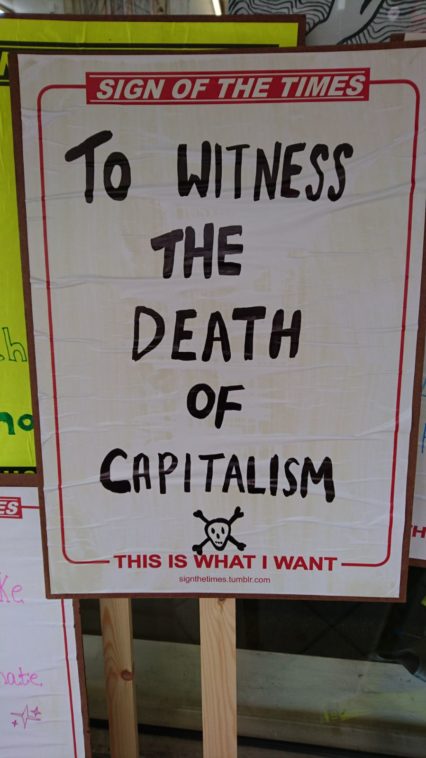

I later joined the procession, where anyone was invited in a fun and celebratory march with placards made by the revellers, two minutes up the road to the derelict Palace Theatre. As the procession arrived its destination, I was immediately reminded of the dichotomous relationship this street has always had, between challenge and opportunity.

Directly opposite the Palace is the Dyfatty social housing estate, which has for decades been a hotbed for crime, drug problems, poverty and low employment in the city. As I watched, I was approached by one of the residents who asked me what was going on. After I explained, he said it sounded like a nice idea but had no idea that two minutes away from his doorstep was a four day arts festival.

Engaging with people from the area was a challenge that the organisers were aware of and was central to what they were hoping the Troublemakers’ Festival could encourage. As Carrie stated, ‘Volcano are very committed to be a part of the community here, to be part of the development of the area… it’s a diverse demographic and the festival is asking people to give something and to participate. It’s an attitude that we are trying to stimulate a bit more of in the High street, that sense you have a right to be involved, everybody should have a voice, everyone’s voice should be heard.’

Failing to reach those from the surrounding area is a constant challenge that arts led regeneration has often been criticised for. Sometimes referred to as ‘artwashing’, it has been accused of exclusivity with a failure to engage those locally who are often from marginalised backgrounds.

Key to trying to prevent this has been the partnership with coastal housing and making the vast majority of the festival free (bar a few ticketed events). Seen as ‘vital’, Carrie expressed how the collaboration has opened up opportunities that might not have otherwise been possible. ‘There’s the instrumental side to it, useful for communications, access and gatekeeping, which allows us to get leaflets through people’s doors. We’re also running a workshop, where over-55’s from the local area can go, that wouldn’t happen so easily if we didn’t have the way through coastal. But also it’s about how organisations work and how they define things like engagement differently. We have a lot in common, we want the best for people who live in the area, there’s a lot of unexplored territory there.’

The unexplored is a key term here, as the festival was as much about experimenting to see how the High Street can be used in the future and keep evolving, as it was about enjoyment. On the whole, it achieved this with many of the events and activities open ended to encourage participation and immerse festivalgoers in the street. However, how well-engaged those from the area were will be difficult to assess and one can’t help but feel that this task is an ongoing one that continuously needs to be worked at.

For example, on Friday night, Volcano Theatre hosted a show by Gaggle Productions – a whirlwind set of monumental speeches by women throughout the ages. Before the show, sat directly opposite the Volcano Theatre were two people begging for money who were completely oblivious to what was going on. After the event, there was also a disco and drinks event open to all, but one only need to look out the window for five minutes to notice the amount of local people from the area walking past without even looking in.

This could have been that they were just not bothered about art, but there was also a sense of the inevitable, that despite best intentions, as this becomes a more desirable area, it could marginalise those who could benefit from such development the most.

This will remain the biggest challenge that the High street will face. Like any good art piece, the Troublemakers’ Festival asked more questions than it answered. It is difficult to know whether it can continue to hold its values of inclusivity and create an arts quarter which belongs as much to those who live close by as it does the to the artists who occupy the buildings.

In parts of Brooklyn, New York, rent freezes have been introduced along with collaborative arts programmes to positively impact areas without creating too many divides. This is something that could be considered in Swansea so that the arts and the local area can consume each other in positive and mutually beneficial ways.

How this develops is part of the exciting experiment that the Troublemakers’ Festival hopes to begin and one could look towards the Palace Theatre for inspiration. A symbol of resilience, it was one of few buildings on the High Street that was not damaged during the Blitz. When constructed for £10,000 in 1888, it was done so in order to re-generate the area. Its re-generation could therefore be a further sign of positive change and it is this resilience that those invested in the street should rely upon so it can really develop into an inclusive and thriving area that people from all walks of life can be proud of and claim ownership over.

If the transformation of the street can be a success and approached with the same enthusiasm and passion that the Troublemakers’ organisers showed this weekend, then the High Street could be pivotal in Swansea’s bid to become the UK City of Culture in 2021.