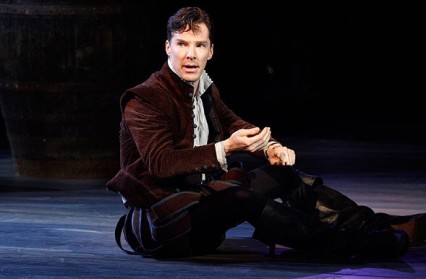

Nicola Edwards casts a critical eye over Benedict Cumberbatch’s performance in Hamlet, a National Theatre production directed by Lyndsey Turner.

There have been a myriad Hamlets in recent years. David Tennant arguably was the catalyst, with his desperate and feverish depiction of the Dane at the RSC. John Simm continued the trend with his vitriolic performance at The Crucible in Sheffield. Then there was the truly superb Rory Kinnear, whose multi-layered and supremely intelligent portrayal of Hamlet revealed all the subtle nuances of Shakespeare’s most complex character. And now, we have Benedict Cumberbatch, one of our greatest and most lauded actors taking on the part all great actors must, at some point in their youth, attempt. His is a fair attempt in a production that is at best interesting and at worst fragmented, chaotic and even, at times, misguided.

The director, Lyndsey Turner, has made some questionable choices. There was much in the press, after the initial previews, of her decision to begin the play with the ‘to be or not to be’ soliloquy. In the final performance the soliloquy is back close to where it should be, but Turner has still clumsily hacked at the play’s structure with a blunt instrument. The tense, atmospheric first scene with the introduction of the ghost is gone. Instead, the audience is presented with Cumberbatch, alone on stage with a portable record player and sifting nostalgically through old photographs. A tattooed, backpacked and consistently breathless Horatio intrudes on his friend’s solitude and we are given a brief explanation of the situation in Denmark. Omitting the opening scene considerably weakens the beginning of the play. The almost total re-writing and shortening of the play within the play, or ‘The Mousetrap’ as it is known, turns a pivotal point in Hamlet into merely a distraction. The use of slow motion during the soliloquies is initially a novel idea, but by Hamlet’s third speech it is too easy to look past Cumberbatch and watch the actors around him perform their bizarre moon walks. Even the grandiose stage design, although beautiful, deflects from the action of the play. Hamlet’s ‘distracted globe’ becomes an epidemic in this production.

The central performances seem to suffer from the structural and stylistic constraints that are enforced on them. The most disappointing is the frustratingly fragile Ophelia, a lazy and unchallenging interpretation that jars with Turner’s more experimental touches. Cumberbatch makes a very serious Hamlet; a moral man caught in an immoral world. When Hamlet adopts his ‘antic disposition’, Cumberbatch is magnificent, reminiscent of his whirling and energetic performance in Sherlock. He delivers Hamlet’s witticisms as though they are his own, but in other areas his performance is less convincing. Hamlet’s frustration at his inability to act is clear, but his grief and despair are less believable. Even during his two great meditations on death and suicide, it is questionable whether Cumberbatch’s Hamlet really wants to end his life. He never lays himself bare, not even in the soliloquies, perhaps because he is made to deliver them against a freeze-frame of the very characters that inhibit him.

Hamlet answers Claudius’ attack on his grief with the assertion that he is not ‘playing’ at mourning, that his heartbreak is genuine. Unfortunately Cumberbatch’s depiction of this grief is entirely that – an obvious act. After marvelling at his performance as both the creature and as Frankenstein in the eponymous play directed by Danny Boyle, Cumberbatch is more than capable of ‘laying himself bare’ on stage. Perhaps what is missing in this production of Hamlet is a director who allows him to take centre stage.

Nicola Edwards is a regular contributor to Wales Arts Review.