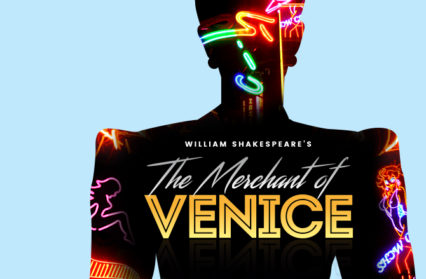

Thomas Tyrell visits Cardiff’s Everyman Theatre for a performance of Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice set in the 1980s.

The plots of many of Shakespeare’s comedies work better if you assume the characters are drunk most of the time. Joss Whedon’s film of Much Ado About Nothing (2013) did this well, setting the play at a boozy Californian house party, but Cardiff’s Everyman Theatre production of The Merchant of Venice takes it to the next level, taking the play to the high-octane, high finance, high-as-a-kite world of the 80s, where women with big hair and men with ludicrous lapels snort cocaine and gulp down Quaaludes in vast quantities. Think Wolf of Wall Street does Shakespeare, and you won’t be far off.

The sets, like the decade, are not exactly subtle. On one side of the stage, Portia’s Palazzo, the Belmont, is rendered as a gloriously tacky cocktail bar. On the other, a wall-sized image of argosies and galleons sailing between corporate megaliths reinforces the melding of two great ages of trade and finance. Badly-placed microphones mean that every squeak of the actor’s shoes is sometimes wincingly amplified, but the sight of the full moon rising behind the treetop backdrop of the outdoor theatre didn’t fail to cast a little magic over the scene.

So, does the 80s setting help the play or harm it? In Merchant of Venice, Shakespeare wrote some of the least likeable heroes of his career: the two chief character traits of the titular merchant, Antonio, are moping and virulent antisemitism. Turning them into pill-popping Masters of the Universe certainly doesn’t soften their edges, and Laurence Clark’s charismatic Shylock stands out against this background as the only character not swept up in this culture of thoughtless hedonism. A brief scene of him alone in his office listening to classical music stands out by contrast with the thumping 80s synth anthems that dominate the stage throughout. Another clever addition to this script is a mute scene where Shylock, searching for his absconded daughter Jessica in the chaos of a street party, is beaten up by a gang of revellers in animal masks; among them Antonio, who lurks behind a terrifying swine’s snout.

It’s a real kicker of a scene, which not only reveals the nastiest line in the play, Shylock’s reported howl of “My daughter! O my ducats! O my daughter!” as false mockery from a bigoted character, but also gives new force to Shylock’s greatest speech, which moves from asserting the common humanity of Jew and Christian (“If you prick us, do we not bleed? If you tickle us, do we not laugh?”) to announcing his desire to enact revenge by simple Christian example (“And if you wrong us, shall we not revenge? If we are like you in the rest, we will resemble you in that”). By the courtroom scene, the effect is like watching Die Hard (1988) in a version where Bruce Willis never shows up to the party, and the whole audience is rooting for Alan Rickman to bring this skyscraper full of awful 80s personalities down in flames.

Meanwhile the B plot, the wooing of Portia by two unworthy suitors and the worthy Bassanio, ensures the mood doesn’t get too bleak. The sequinned machismo of Ash Heirani’s rockstar Prince of Morocco is hugely entertaining, but it’s Chris Kendrick who steals this scene, channelling Adam and the Ants as the achingly New Romantic Prince of Aragon, and more than earning the spontaneous round of applause that broke out as he left the stage. Sarah Green’s prickly, cut glass Portia is a magnificently poised creation who might have walked in from an early Jilly Cooper novel, and from the moment she walks into the courtroom (disguised, inevitably, as a man), the play is hers, not Shylock’s. She turns language and the law on its head, saves Antonio’s life, confiscates Shylock’s whole fortune, and compels him to convert to Christianity. Bankrupt, baffled and humiliated, Shylock flees, and after some kerfuffle with rings that was probably pretty tiresome even back in the sixteenth century, the play closes with Portia standing on the bar at the Belmont with her best pal Nerissa, performing a ferocious karaoke version of the Eurythmics / Aretha Franklin classic ‘Sisters Are Doin’ It For Themselves’.

Many productions close with a scene revealing Shylock’s fate: the most recent Globe production with Jonathan Pryce showed us his forced conversion in all its ghastly pomp, while the 2004 Al Pacino movie had him ruined but true to his faith, fishing on the Venetian shoreline. Closing with an upbeat feminist karaoke number, the Everyman Theatre production eschews this focus on the antisemitism of the times for a celebration of the power of Shakespeare’s proto-feminist heroine. If the result does something of a disservice to their terrific Shylock, it’s nonetheless a play that’s toe-tapping and infectiously entertaining.

Thomas Tyrrell is a regular contributor to Wales Arts Review.