Adam Somerset reviews Patagonia, a BBC Cymru Wales‘ documentary exploring the history of the Welsh South American settlement.

Patagonia has three prime virtues. The most obvious is that film captures the visual appearance of the geography. The camera cuts to signs of streets named Juan C Evans and Michael D Jones. The engineering prowess and achievement of the first settlers are shown in a sequence where Huw Edwards stands by a canal. It is one of many, part of a large-scale system of irrigation. They are sixty kilometres from the source river itself, says his interviewee. Director Marc Edwards adds a picture from satellite distance. The Welsh creation has indeed been, after the multiple early trials and difficulties, to make from the Patagonian steppe of scrub and thorn a place of bloom.

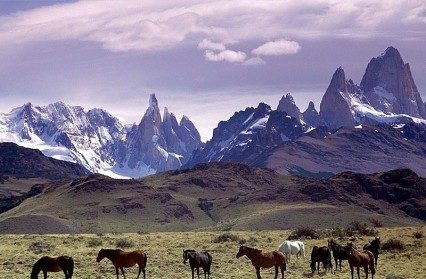

The characteristic topography has been depicted by writers from W H Hudson to Paul Theroux. It is made vividly clear in the film’s journey inland, following the route pioneered by John Daniel Evans and the rifleros to Cwmhyfryd. In the great open landscape, a line of snow-capped Andean peaks in the background, Alejandro Jones, a young Welsh-speaking farmer, lassoes a calf. The scene is reminder that Huw Edwards’ opening line, ‘It is our very own Wild West epic’, is no hyperbole. In charting the arc of the colony’s story another introductory sentence, ‘It is one of the greatest adventures in the history of Wales’, sounds all too true.

It is this tracing of the story of Welsh Patagonia through to the present day that is probably most revealing, not least for what it reflects about the state of Argentina. Grown-up history is not a comfort blanket. It is to the credit of the Edwards duo, director and presenter, that they do not skirt around the facts of history that discomfort.

The crossing itself was an ordeal. The economy necessitated by the film’s fifty-eight minutes does not dwell on the sour relations that developed with the Captain of the Mimosa. Four babies died in transit and the barren coast soon claimed a first death. A local historian is guide to a series of natural rock caves and hollows which the settlers used for storage and for possible human shelter. Huw Edwards holds a faded pamphlet written by Hugh Hughes and the script says simply, ‘Those first settlers had been very badly misled.’ It is not the only instance where fantastic claims of natural fecundity were made to embolden settlers. It is the theme of Jonathan Raban’s 1996 Bad Land. But the modern view can hardly escape a judgement that the promoters hovered somewhere on a spectrum between wilful fiction-making and direct duplicitousness

The intention was ‘a new Wales marked out by cultural purity’. To its credit the film looks unabashedly at the paradox beneath the aspiration. The allocation of the land was made by fiat from the far-off government in Buenos Aires. With agricultural prosperity a process years in the making hunting was a necessity for the settlers. The Tehuelche Indians were their tutors. There is an irony, says the script, to an oppressed minority moving in on land lived on by others. The Tehuelche were to suffer terribly in Roca’s 1880’s war that generated a murderous attack on four Welsh settlers in response. At the time of the arrival of the Mimosa, the Argentine government was making payments to the indigenous populations not to attack settlers. The historical record is not clear-cut but, opines the film, the terms of trade between Welsh and Tehuelche were not always equitable. As for alcohol it certainly came into the teetotal community and the likelihood is that it was passed on to the host population.

A television script has a necessary leanness to it. The film dips in and out of the relationship with the state. A self-determining community was not the goal of the Welsh alone. Nietzsche’s sister was behind one seeking Aryan purity in neighbouring Paraguay. Mennonite farms of an extraordinary pristineness dot the Americas. But since the settlement was an act of government policy – the intention to see off the territorial claims of Chile – it was inevitable that the state should exert its authority. An early cause for friction was the stipulation that army drills be performed on a Sunday. In the 1890’s two hundred and fifty Welsh moved on to Canada.

Welsh Patagonia was as hostage as anywhere to events beyond. Early wheat strains may have won awards at a World Fair but the Depression put paid to the agricultural co-operative that was key to the region’s prosperity. Perhaps diplomatically the film does not mention Peron. But the script does say baldly that the canal system was nationalised in the 1940’s and the Eisteddfod came to an end in early 1950’s. Popular argot developed a pejorative term for Argentines who adhered to a non-Hispanic identity.

And then it all changed. ‘Nationalism waned in favour of diversity,’ says Edwards. The economic base of Patagonia moved from hard-won agriculture to tourism. The centenary of the arrival saw the reinstatement of the Eisteddfod. Gaiman had its first Welsh-speaking mayor since the 1950’s. The chapels became recipients of government repair funding, their status changing from witness to the glory of God to visitor attraction.

The film visits the Provincial Governor in Rawson. With the passage of a century and a half y Gwladfa has become part of the national story. The Governor speaks with pride about the greening of the steppe and the making of the historic railway. The vote of those of Cwmhyfryd who rejected the offer to become part of Chile has made them heroes. The film is witness to present-day pageants, parades and re-enactments of the arrival of the Rifleros.

Yet the century-and-a-half on means more than the region’s enrolment into national heritage. The bulk of the film is made up of Huw Edwards’ encounters with the real stuff of history, the people of Chubut. The interviews are warm and easeful, the interviewer never losing that sense of novelty to be sharing a common language seven thousand miles from home. He hears accordion-accompanied folksong, eats heartily at a traditional outdoor feast. He draws a passable tune from a chapel organ that arrived on the Mimosa. ‘Faith and non-conformity were crucial,’ says the pastor who has acquired Welsh.

In Esquel the film visits the first bilingual primary school. Intriguingly, many of the pupils are not of Welsh ancestry. The commitment of the parents is evident in the fee structure. The Spanish part is free, the Welsh element paid for.

These are not the easiest of days for public television. No corporation other than the BBC would have set about this venture. Patagonia is enquiring, open-minded, structured. There is the inevitable excess of music, but that is in 2015 obligatory for all documentaries. At least the music is all picked out on guitar with a Latin flavour. Twelve hundred new learners are studying the language, a number not large but one that would astonish an observer from fifty years back. Trevelin may now be a sizeable hundred thousand strong but as a grizzled interviewee says ’round here they call us “galeses”’.

Adam Somerset is an essayist and a regular contributor to Wales Arts Review.