David Cottis reviews Lyndsey Turner’s new production of Dylan Thomas’ classic masterpiece Under Milk Wood, starring Michael Sheen, Karl Johnson and Siân Phillips.

After eighteen months if which most of us haven’t been in any groups larger than a small dinner party, it makes sense that the London National Theatre should reopen with Under Milk Wood, a play which, although it doesn’t exactly celebrate community, certainly creates one. In fact, the inhabitants of Llareggub are the kind of people who would have coped well with lockdown – a solipsistic bunch, who spend remarkably little time in each other’s company, and who are defined by their obsessions, whether these be sex, horology, or wife-murder. It’s worth remembering that at one stage in the writing, Dylan Thomas ended the play with the entire village on trial for insanity.

This is theatre as an act of defiance – the audience queues up outside, a little Blitz-spirit banter tiding over the inevitable confusions and awkwardness, as we check in on the NHS app, and make our way, individually, to our seats. The Olivier auditorium has been reconfigured in the round, with spaces for social distancing, leading to the strange experience of being in a theatre that you know is a full house, even though it’s half-empty.

Although it was once, as Carl Tighe wrote in 1986, ‘the Welsh play against all others are judged’, Under Milk Wood isn’t, strictly speaking, a play; it was written for radio, and first performed in that medium in 1954, shortly after the author’s death. Many of its most memorable moments gain their strength from their invisibility – an image like ‘Mr Beynon, in butcher’s bloodied apron, spring-heels down Coronation Street, a finger, not his own, in his mouth’ loses its power if you can see it. (It’s not a coincidence that the main named character, Captain Cat – here played by the estimable Anthony O’Donnell – is blind.) Any production on stage or film has to walk a tightrope; play down the visuals and you end up with something that might as well be on the radio, ramp them up, as the 1971 film did, and you get the problem of redundancy.

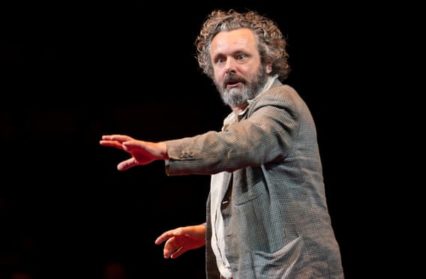

Given these two dangers, Lyndsey Turner’s production goes for a sort of middle way, through a framing device incorporating new material by Newport playwright Sian Owen. In this version, we are in a care home where the First Voice – played by Michael Sheen, following in the Port Talbot footsteps of Burton and Hopkins – becomes Owain Jenkins, a son seeking to reawaken his elderly father’s memory of his childhood home. As he carries on, the father (Karl Johnson), other inmates and staff get drawn into the story, dividing up the many characters between them.

It’s a device that adds a narrative to a work that conspicuously lacks one, and it leads to some nice touches – it’s very satisfying when an officious senior nurse turns into the germophobic Mrs Ogmore-Pritchard. The generally older cast add a note of elegy – this is a Llareggub that doesn’t exist now, if it ever did, and when Sian Phillips plays the flirtatious Polly Garter, we see the character’s past and present co-existing in the same person, like the child/adults in Dennis Potter’s Blue Remembered Hills. The tone is darker here than in many productions – Cherry Owens’ drunkenness is played for pathos, not laughs, and Garter’s ‘Isn’t life a terrible thing, thank God?’ feels hollow.

At other times, the device is a bit of a distraction – Sheen sometimes seems hobbled by having to play so much of the part to one person, and it occasionally gives the piece the feel of the last scene of Psycho – a rational explanation of something that works better without it. It’s also unfair to expect Owen to match the quality of Thomas’ prose – like Hamlet, it’s a play that sometimes seems to be made up entirely of quotes: ‘Nothing grows in our garden, only washing. And babies’, ‘Praise the Lord! We are a musical nation’, ‘And before you let the sun in, mind it wipes its shoes.’

Turner adds some effective visual touches – a series of breakfast scenes set at the same table with changing clothes captures some of the right shape-shifting tone – but this felt, at least at the preview performance I saw, under-powered, a production hamstrung by the decision not ‘to begin at the beginning’.

Photo credit: Michael Sheen in Under Milk Wood: Johan Persson

Under Milk Wood is showing at the National’s Olivier theatre until 24 July.