When do current affairs become recent history? In the UK, the ‘thirty-year rule’ governing the release of cabinet papers to the National Archives would suggest three decades as a rule of thumb, a supposed safety valve on potentially contentious material. It is also a period of retrospection that gives the contemporary novelist enough vantage to avoid her work becoming a kind of ultra-longform journalism.

When do current affairs become recent history? In the UK, the ‘thirty-year rule’ governing the release of cabinet papers to the National Archives would suggest three decades as a rule of thumb, a supposed safety valve on potentially contentious material. It is also a period of retrospection that gives the contemporary novelist enough vantage to avoid her work becoming a kind of ultra-longform journalism.

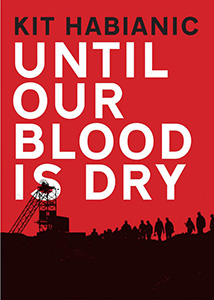

As has been revisited in everything from Billy Elliot through David Peace’s novel GB84 to Manic Street Preachers’ recent song ’30-Year War’, the Miners’ Strike of 1984-5 was a watershed moment not only in industrial relations but in working class consciousness and British history, and it is this almost mercilessly heavy baggage that forms the backdrop to Until Our Blood is Dry. All of which is to say: it is a brave subject for a debut novel.

Habianic pulls it off. With the simple section titles – ‘Winter 1984’, ‘Summer 1984’ – there is a feeling that maybe this is a novel that aspires to a universality that might threaten to unravel the project before it is even begun. But right from that beginning – ‘Mid-evening and the Red Lion was empty…’ – we are pulled into a very specific story. Gwyn Pritchard is sitting at his usual table mulling over an accident. But we already know – from a radio transcript that prefaces the book – that this man, described by the area manager as ‘a solid family man who died defending his right to go to work’, is dead.

What we don’t know – yet – is that the official obituary for Gwyn Pritchard is not only deeply disingenuous, but outrageously incorrect. The story of Until Our Blood is Gwyn’s story, but – and this is crucial – it is also his daughter Helen’s story. It is a story that does not forget women, and as such – and to its own betterment – becomes much more about human drama than union politics. Of course Thatcher’s assault on the mining industry forms the backdrop – the then Prime Minister makes a couple of cameo appearances on television – but for the most part the events of the novel are intensely local.

Difficult choices provide the drama. Until Our Blood Is Dry has the episodic intensity of a soap opera. We are carried along by wanting to know whether Helen will leave home, whether she will keep the baby, whether her dad will ever back down. We come to care deeply for Helen ‘Red’ Pritchard, for her lover ‘Scrapper’ Jones and his half-Welsh, half-Italian family at the bracchi, even for poor Helen’s mam. As the strike hardens and both sides become entrenched in their positions, life is not easy for any of them.

We do, however, find it difficult to care for Gwyn. Such is his intransigence, his bloody-mindedness, his sacrifice of family to the ‘duties’ of the workplace, that we begin to share Helen’s resentment – and possibly outright hatred – of her father. But Habianic’s skill is such that by the time the final drama plays out, we know that all here are losers. The Miners Strike of 1984-5 was nothing if not a tragedy, and if we cannot quite bring ourselves to see Gwyn Pritchard as a tragic hero, then a tragic villain he will have to remain.

Until Our Blood Is Dry does not, quite, compare with some of the classics of Welsh industrial literature. As a literary work, Habianic’s book feels heavy on characterisation and plot and light on metaphorical or symbolic resonance. But on its own terms, it is a roaring success: a gripping and ultimately moving novel that fills a gap in our national story. Now that the arbitrary thirty years have elapsed, I am sure also that it won’t be the last fictional return to the events of 1984-5. As a time where so many truths were obfuscated with lies, it is a story that needs to be told and retold. Until.