In celebration of #DylanDay 2017, Professor John Goodby remembers the unveiling of the fabled Dylan Thomas Fifth Notebook in 2015.

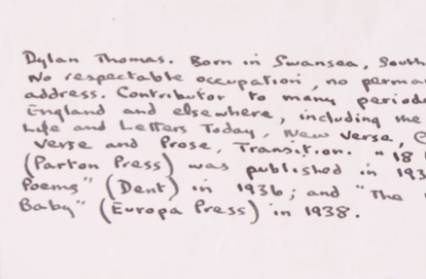

‘In the evening, before calling on my new friend, I sat in my bedroom by the boiler and read through my exercise-books full of poems. There were Danger Don’ts on the backs. On my bedroom walls were pictures of Shakespeare, Walter de la Mare … Robert Browning … Rupert Brooke … and a Sunday school certificate I was ashamed to want to pull down’. So admits Dylan Thomas in ‘The Fight’, his short story of 1938, in which he gently mocks his precocious younger self. Until last year, just four of these ‘exercise-books full of poems’, covering the period 1930 to April 1934 and held at Buffalo, were known to have survived. Although they were the source of most of the poems in his first two published poetry collections, sixteen of the poems in the collections were not in them. Tantalisingly, it was known that Thomas had continued his practice of copying finished poems into ‘exercise books’ well into 1935. But no more had appeared since he sold the four to Buffalo in 1941; by 2014 very few dared to dream that any more of them could have survived.

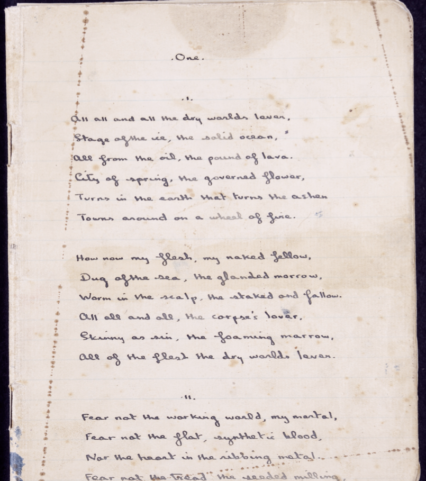

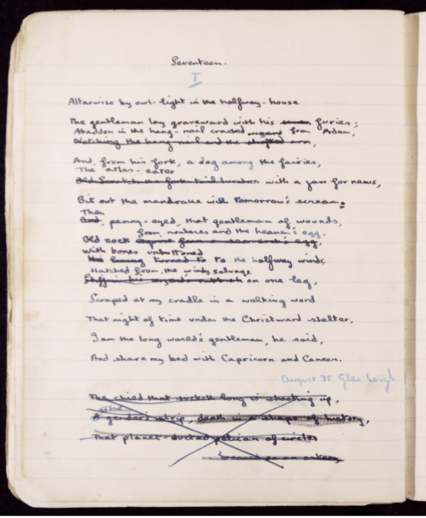

This is why the fifth exercise book was such an astonishing discovery. I first made its acquaintance in a hotel room in Manchester, last October, when I was allowed to look through it by Gabriel Heaton of Sotheby’s not long before the three of us appeared together on BBC Breakfast. It was a thrilling moment, because it was clear that it was precisely what Thomas scholars had been looking for, a direct continuation of the first four notebooks. It runs from April 1934 to August 1935, and contains the source texts for all but two of the ‘missing’ poems. Many of the poems in it are also dated, and a place of their completion given. This has already altered the sequence in which we thought the poems were composed, and told us if they were completed in Swansea, London, Cheshire or Donegal, the places he inhabited during this footloose and fancy-free period. And, even more than his physical travels, the notebook allows us to trace Thomas’ adventures through new and startling poetic territories, as he pushed poetic language and the lyric form to new limits in ‘Altarwise by owl-light’ and ‘I, in my intricate image’, the most ambitious poems he would ever write. Most of all, as you go through the notebook, the complexity of the poems increases and, as a result I think, so too do the numbers of revisions. It’s these that give the notebook its primary importance; you can see how Thomas gives a fresh twist to a surreal image, coins an idiom, ‘dislocates the language’ into new meaning. In effect, they’re an X-ray of the final stages of the creative process. Bringing the notebook back home, then, helps to confirm Swansea’s position as the centre of future of work on Thomas, fresh evidence of which can be seen in this study of Thomas’s early poems by my former student Rhian Bubear, published just a few months ago.

This is why the fifth exercise book was such an astonishing discovery. I first made its acquaintance in a hotel room in Manchester, last October, when I was allowed to look through it by Gabriel Heaton of Sotheby’s not long before the three of us appeared together on BBC Breakfast. It was a thrilling moment, because it was clear that it was precisely what Thomas scholars had been looking for, a direct continuation of the first four notebooks. It runs from April 1934 to August 1935, and contains the source texts for all but two of the ‘missing’ poems. Many of the poems in it are also dated, and a place of their completion given. This has already altered the sequence in which we thought the poems were composed, and told us if they were completed in Swansea, London, Cheshire or Donegal, the places he inhabited during this footloose and fancy-free period. And, even more than his physical travels, the notebook allows us to trace Thomas’ adventures through new and startling poetic territories, as he pushed poetic language and the lyric form to new limits in ‘Altarwise by owl-light’ and ‘I, in my intricate image’, the most ambitious poems he would ever write. Most of all, as you go through the notebook, the complexity of the poems increases and, as a result I think, so too do the numbers of revisions. It’s these that give the notebook its primary importance; you can see how Thomas gives a fresh twist to a surreal image, coins an idiom, ‘dislocates the language’ into new meaning. In effect, they’re an X-ray of the final stages of the creative process. Bringing the notebook back home, then, helps to confirm Swansea’s position as the centre of future of work on Thomas, fresh evidence of which can be seen in this study of Thomas’s early poems by my former student Rhian Bubear, published just a few months ago.

These considerations bring me back to what is truly important about Dylan Thomas on this first Dylan Day. What I enjoyed most about the centenary was how it became the occasion, for the first time since devolution, for a shared cultural celebration across Wales. But if I could enter a minor Danger Don’t of my own, the poems weren’t really given much of a look-in. Not that the razzmatazz wasn’t great fun, but in future I hope the focus will be expanded beyond more than just a handful of his most easily understandable works. Not to do so risks trapping him in sentimentality and the laddish legend. The essence of Thomas is his poetry, and almost all of it can be made accessible to most people; we therefore need to be bolder in explaining the ‘craft and sullen art’, a bit less willing to fall back on ‘the strut and trade of charms / On the ivory stages’. Thomas is a subverter of stereotypes, so he shouldn’t be turned into one; he appeals to people because they instinctively sense his rebelliousness, and if we make him bland and predictable we will kill the goose that lays the golden eggs. First and foremost, as the notebook here reminds us, Dylan Thomas was a great poet, and he is as relevant to our twenty-first century world as he was to his own. He was one of the first eco-aware Green poets, a ‘mental militarist’ and ‘militant pacifist’ who despised war and opposed nuclear weapons, a socialist who attempted in his writings to liberate mind, body and imagination. Above all, his ‘lovely gift of the gab’, dark wit, and revolution of the word, sets an example of how we too can resist the language of corporate power, bureaucratic authority and supine conformity.

These considerations bring me back to what is truly important about Dylan Thomas on this first Dylan Day. What I enjoyed most about the centenary was how it became the occasion, for the first time since devolution, for a shared cultural celebration across Wales. But if I could enter a minor Danger Don’t of my own, the poems weren’t really given much of a look-in. Not that the razzmatazz wasn’t great fun, but in future I hope the focus will be expanded beyond more than just a handful of his most easily understandable works. Not to do so risks trapping him in sentimentality and the laddish legend. The essence of Thomas is his poetry, and almost all of it can be made accessible to most people; we therefore need to be bolder in explaining the ‘craft and sullen art’, a bit less willing to fall back on ‘the strut and trade of charms / On the ivory stages’. Thomas is a subverter of stereotypes, so he shouldn’t be turned into one; he appeals to people because they instinctively sense his rebelliousness, and if we make him bland and predictable we will kill the goose that lays the golden eggs. First and foremost, as the notebook here reminds us, Dylan Thomas was a great poet, and he is as relevant to our twenty-first century world as he was to his own. He was one of the first eco-aware Green poets, a ‘mental militarist’ and ‘militant pacifist’ who despised war and opposed nuclear weapons, a socialist who attempted in his writings to liberate mind, body and imagination. Above all, his ‘lovely gift of the gab’, dark wit, and revolution of the word, sets an example of how we too can resist the language of corporate power, bureaucratic authority and supine conformity.

Images courtesy of John Goodby

You might also like…

In the first of four exclusive extracts in the lead up to this year’s Dylan Day, leading Thomas expert Professor John Goodby explores several aspects of what we know about Thomas, and what we only thought we knew. As with so much relating to Dylan Thomas, writes John Goodby in the introduction to his hotly anticipated new book, Discovering Dylan Thomas, the story of the discovery of the fifth notebook is both entertaining and intriguing.

This piece is part of Wales Arts Review’s collection, Dylan Thomas from the Archive.

John Goodby is a Dylan Thomas expert and contributor to Wales Arts Review.