Zion Lights discusses the importance of producing positive stories about the future and questions the ability of dystopian climate fiction in capturing the spirit and imagination of humanity in her essay Visions of the Future. A future burnt with fire is our fate, and climate dystopian fiction will forever heighten the risks and scarability of these predictions.

I grew up in a household where it was normal to make jokes about Marty McFly, randomly shout “exterminate!” at siblings, and announce “I’ll be back” before visiting the bathroom. Sci-fi for me has always been an escape from the world and a chance to explore imagined realities and futures, but with my understanding of climate change, I am no longer able to emotionally disconnect from a potential future that has been devastated by global warming. While watching The Road with my friends, for the first and only time I walked out of the cinema because all I could imagine during the harrowing scenes were the studies I’d read of potential future warfare scenarios, habitat degradation and starvation. Even though I’d read the book beforehand, I cried when I saw on the big screen the extreme reality of the world my two children might one day have to face.

I noticed a change of theme in sci-fi books in the late 2000s. Writers had clearly become worried about the environment and wanted to explore future scenarios. I thought it was cool – as a long-term environmentalist the advent of ‘climate fiction’ was music to my ears. It’s basically a loosely-termed type of sci-fi that is predominantly concerned with environmental issues.

The popularity of climate fiction, or cli-fi, is unsurprising since sci-fi has always been good at exploring the potential impact of new technologies. What surprises me though is how predominantly negative the future scenarios in popular cli-fi are. I wondered whether it was having an impact on people growing up in a climate-changed world, so I dedicated my Masters’ thesis to exploring the topic.

The problem my research encountered was that less than ten mainstream cli-fi books fell into the non-dystopian, or utopian, category at the time. Why is there so much apocalyptic cli-fi? Do we simply prefer to read doom and gloom scenarios? Or are writers struggling to envision positive outcomes? Is a future burnt with fire really possible?

Blessed are the storytellers, for they show us what is possible

Storytelling is crucial to science. Without telling the story of its development or potential application, any scientific discovery can become meaningless to society. Yes, a vaccine may be life-saving and world-changing, but if the story that it is harmful is more convincing than the truth – that it will save lives – then too few people will have the vaccine, rendering the research and discovery near-useless.

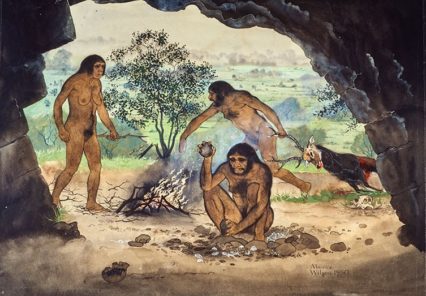

But let’s zoom out again. The ability to weave a narrative has long been essential to our evolution. In fact, research has found that throughout human history skilled storytellers have been the most preferred social partners, Even when we roamed the land without static homes and all the other perks of civilisation, storytellers had the most offspring. Pause for a moment and let that sink in. It wasn’t the people who provided food, or shelter, or protection from predators who had the most babies. It was the narrators.

It’s not difficult to see why. Storytellers brought people together. They could capture human imagination to provide mental warmth on a cold night. They could play with emotions, creating space for grief, anger, fear, love and more in a single sitting. Through their tales, they instilled values in children long before classrooms and temples existed. They looked up at the stars, named the constellations after the Gods, and used them to teach different morals as the planet rotated and their starry canvas changed. On the other side of the planet, they taught children the story of the Emu in the Sky, which reminded everyone, young and old, of their connection to the land and to the wild, and of their place in the universe.

A Future Burnt With Fire | Climate Dystopian Fiction

This fundamental human condition has not changed. Today we revere the writers, actors and directors who are able to transport us to another place using words and pictures. We no longer gather around the fireplace, but those that help us to imagine still enthral us. A future burnt with fire excites us.

Over time we have forgotten the old stories. We still use the Greek names for constellations, but no longer know the stories behind them. We retell Shakespeare but appreciate that much of it requires cultural context to be fully understood. We use the days of the week, but few of us know the origins of their names (the Romans named them after their gods, corresponding to the five known planets plus the sun and moon, which the Romans also classed as planets). You might argue that those stories are irrelevant to us now, and out of place, which leads to my next question: what are the stories of today? Where are the narratives that bring us together, that help us to understand our place in the universe now? Which tales drive out the darkness and the fear?

These are pertinent questions in increasingly secular times and during an era of climate change that has created an existential crisis of sorts. The ability to envision the future was once essential for our species: indeed, mental time travel may have been one of the earliest mental faculties early humans developed.

If most cli-fi is dystopian then perhaps storytelling has lost its place, its relevance. It’s the ability to explore possibilities based on cooperation and innovation. We have lost spirituality, not in a religious way, but in terms of a connection to something bigger, to philosophical wonderings, to the night sky. We seem to have lost our place amongst the stars.

The fire that stoked our imaginations

A Future Burnt With Fire | Climate Dystopian Fiction

The fire was once a revered gift that was worshipped. We don’t know exactly when the first humans started to use fire, but scientists have found that the gut of the human ancestor Homo erectus began shrinking around two million years ago, which suggests that cooking foods were making digestion easier. In order to cook, they must have used fire.

The first Homo erectus to work out how to capture fire from a wild blaze, and use it to cook, was a visionary. Early humans must have had a surprise. Some would have received this new discovery with awe, even reverence, while others would have gotten burned – literally – and rejected it.

Such is the power of fear. Fear of a vaccine, fear of GMOs. Two million years later we retain the same evolutionary propensity for fear of the new and the unknown, and we also harbour the same immense potential for innovation and exploration. Other early humans gave the fire a chance and discovered that it kept them warm on cold nights. That it provided light on dark nights and warded off predators and flies. In the process of exploration they learned how to sharpen a flint, attach a flint to a piece of wood to create a spear, and create digging tools. This led to more effective hunting through weapons, the ability to secure food supplies and in turn the formation of agriculture and civilisation. We harnessed mechanical labour of animals, wind and water and the use of fire for smelting, taking us from stone to bronze to iron age, coal, then oil and gas enabling industrial revolution and the lifting of many people out of subsistence living. It was the literal flame that ignited an explosion of science and technology. Pioneers led the way.

Who was the first person to discover how to create fire? Who thought that cooking hunted meat using fire might be a good idea? Imagine how the idea came to them, their curiosity and need to know. The first time they sparked aflame with their hands. Their surprise, awe, and disbelief. The consequences of controlled fire were far-reaching. By creating calorie-dense foods through cooking, children grew stronger, and our brains grew bigger. Early humans also used the smoke from a fire to preserve meat. The hearth provided a social focus, which scientists think aided the development of language. Fire enabled us to evolve into the people we are today.

Just as some core evolutionary tendencies of humans have not changed over time, nor have some of our needs. Fire enabled us to gain more nutrition from food, and humans still rely on energy for that purpose. But the process of obtaining energy through fossil fuels has come at a cost, as it is driving climate change and harming us through air pollution. We need a new fire: fire 2.0; energy-dense and reliable, but clean.

Fire 2.0

A Future Burnt With Fire | Climate Dystopian Fiction

This leads me to a more similar example to the catalyst of fire: the discovery of how to split the uranium atom. Nuclear energy comes from the binding energy that is stored in an atom and holds it together. To release the energy, the atom has to be split into smaller atoms. In nuclear power stations, the heat energy released by this splitting boils water to drive turbines to generate electricity.

This energy wields immense potential. Just as with fire, humans learned to tame this incredible discovery, to create an energy-dense source for humanity. It was a process of trial and error, and mistakes were made. But the positive application of this discovery means that our homes stay warm in winter. Vital equipment in our hospitals keeps running, and our lights stay on, without the lung- and heart-crippling air pollution or the global heating caused by the fire we have used since ancient times.

We will never know the stories of the first humans who might have rejected fire. Those that embraced it, who attempted trial and error in learning to manage it, rewarded humankind with their innovation and adaptation. Our stories are their legacy.

Humanity is now at a crossroads: the decisions we make today, of how we heat our homes and cook our meals, will have repercussions for generations to come. The power of the atom is a key solution to addressing climate change, but many people fear it. Politicians across Europe are closing functioning nuclear power stations, committing us to decades more of reliance on the fossil fuels that are harming our planet. There are all kinds of fictional stories about how bad nuclear power is, but the real conspiracy lies in the continued fear of a technological marvel in a space-age era. The truth is out there, for those who want it.

Sometimes people scoff at social sciences, but let’s be honest: society has little use for facts. If the latest wave of anti-science sentiment hasn’t convinced you of that, nothing will. Emotions drive us and gut feelings matter. If we don’t learn how to tell stories that celebrate scientific discoveries and give them context which goes beyond the Black Mirror scenarios of worst-case applications, we are missing a fundamental element to overcoming widespread and increasing pseudoscience.

Personally, I’m worried about all the doom and gloom. If the stories we tell are dystopian, while they might serve a purpose, we are also failing to capture the spirit and imagination of humanity. The full range of human possibilities.

What will the future look like if we manage to do everything right? Can we tell more stories about that too?

I want to imagine a future where my children don’t have the large threat of climate change looming over them. I want to visualise my daughter walking along a street to visit friends:

the spaces around her are abundant with greenery and she stops to pick apples on the way. She smiles at the birds flying overhead, enjoying the autumn day. It has been an ordinary season: an unusually hot day doesn’t make her think of global warming, or fear for her children: she just smiles as the sun beats down on her and she breathes in the clean air.

When she arrives at her friend’s house she greets her with a hug and hands her the apples. They are going to bake a pie. The cooker they use is powered by nuclear energy from a power plant situated in the county next door. The plants are all over the country and she has been to visit more than one, because a tour means something to her: she knows that her mother once fought hard to help build this reality. So that she could pick apples and breathe the air without feeling eco-anxiety. So that she could bake a pie without worrying about the environmental impact of turning on the oven. So that she would get to live in a world that is abundant with life.

Gas is a distant memory, although she remembers the smell of it from her childhood. The sky outside is a bright blue and the leaves are red and orange, changing with the season. She knows the names of all the trees, and their stories as well. Without the threat of climate change hanging over her, and surrounded by countless bird, plant, animal and insect species, there is much in life to look forward to.

Perhaps it’s not as exciting as a story about the apocalypse, but it’s certainly unique. Perhaps I’m imagining a future that is too idyllic, but shouldn’t we be able to visualise the future we all want for our children? Can storytellers once again begin to reach for the stars? After all, that’s partly why storytelling originated. I would certainly welcome a few utopian tales to tuck my children in with at night. This bright, positive potential future has not yet been written, but the reality, and the stories we choose to tell, are in our hands.

If we create a future that runs on clean energy generated by the discovery of the splitting of the atom, we are already halfway toward creating a better world. We will take a leap led by pioneers. As global emissions come down, so do dangerous levels of air pollution. As people attain energy abundance, they are lifted out of poverty. By choosing to embrace the modern-day fire, we will keep ourselves from getting burned in the long run.

Live long, and prosper.

The writer of this A Future Burnt With Fire and Climate Dystopian Future article is Zion Lights, a passionate science advocate and environmental journalist who wants to change the world for the better. She has been a spokesperson for Extinction Rebellion and founder of the XR’s Hourglass Newspaper. She is also the author of The Ultimate Green Hide to Parenting, and the poetry collection Only A Moment.