Adam Somerset takes a walk through the year in the visual arts.

The unmediated meeting of eye and artwork is what matters. But whatever it is that happens when colour and form hit synapse it takes place within a perceptual gestalt. Lighting, hanging and the intrinsic nature of the place all contribute. Goya: the Portraits took ten years in its preparation and is an obvious candidate for England’s exhibition of the year. If Murillo is usually considered Spain’s master-portrayer of children this exhibition included a Goya family group of pure delight. But the National Gallery’s suite of special exhibition rooms is separate and secure. To descend the giant stairs to the below-ground chambers does not induce a cheer of spirit.

Machynlleth’s Museum of Modern Art by contrast has always been a cheering small gem but the adjective “small” probably ceased to apply in 2016. The addition of the new galleries from the adjoining tannery building and the presence of a curator in Lucinda Middleton pitched MOMA to a new level. Peter Wakelin’s freelance status too has been of great benefit to the arts here on the Powys border.

Two principal exhibitions, Ffiniau: Four Painters in Raymond Williams’ Border Country and Romanticism in the Welsh Landscape, were both accompanied by one-day conferences of breadth and vitality. The Wakelin presence on a public platform has an ease and authority that is at one with the curatorial insight and experience.

MOMA also hosted this year a public debate on the tensions between the protection of National Park status and the siting of works of art, or pseudo-art, in the open air. The debate in truth was not really a meeting of minds as it matched general principal against specific example. But the chairing was adroit and Peter Lord was on hand to lob a critical grenade from the floor. The debate’s significance was that it took place at all. As a rule those in the arts who feast most hungrily from the public purse do not host, nor much welcome, debate on the arts. The score in 2016 is Powys one, Cardiff nil.

For the non-specialist, occasional gallery-visitor many of the names on the Machynlleth walls – Craxton, Ravilious, Elwyn, Isaac – were familiar. But that of Joan Baker was less so. Her “Father Feeding the Birds” was a highlight, poignancy added to depth and mood with knowledge of its back-story.

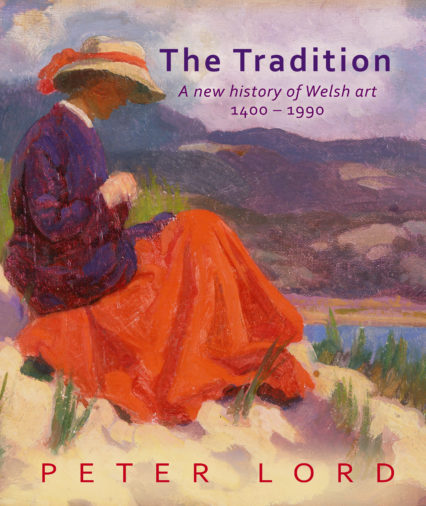

The Tradition, published by Parthian, is likely to be Wales’ art book of the decade. Peter Lord again was active and articulate in its launch. His personal recommendation sent me over the county border into Gwynedd. A Spring morning saw me outside Oriel Plas Glyn-y-Weddw at opening time. The circumstances of time and season made happy preparation for the exhibition of John Cyrlas Williams.

The Tradition, published by Parthian, is likely to be Wales’ art book of the decade. Peter Lord again was active and articulate in its launch. His personal recommendation sent me over the county border into Gwynedd. A Spring morning saw me outside Oriel Plas Glyn-y-Weddw at opening time. The circumstances of time and season made happy preparation for the exhibition of John Cyrlas Williams.

Oriel Plas Glyn-y-Weddw to its credit produced a compact catalogue- it is after all a small gallery in a far-off place from Mountstuart Square. Familiar names are to be seen in the catalogue’s making. Gomer’s reliable hand is there for the quality of print and colour. Peter Lord, perhaps inevitably, is author of the text. If this is the third Peter Lord appearance in a few paragraphs it is no accident. The arts in Wales, or anywhere, are better for an energetic and committed, at times polemical, presence of critical depth. It is not that the Lord view is indisputable, any more than were those of a Lucǻks or Leavis in literary commentary a half-century back. But an engaged critic in the visual arts simply shows up the absence of such a figure in the other art forms of Wales. Most criticism in Cardiff is amplification of the promotional message of the makers. Look only to the response to Artes Mundi.

John Cyrlas Williams’ output was as prodigious as it was compressed. One hundred and fifty pictures survive from a career that had ceased by age thirty. The title for this rich selection was appropriately A Brief Flowering. Highlights included “The Studio”, “The Life Studio, Newlyn” and “Lynne, the Artist’s Sister, at ‘Sandringham’, Porthcawl”.

Lord ‘s look at these works on show at Llanbedrog is particular. Cyrlas Williams, he writes, “was a technically gifted painter.” But it was “not a world of intellectual critique or of intense imagination.” He draws comparison with Archie Griffiths. For Cyrlas Williams, he writes, “rooted in Porthcawl, it was a world insulated from the social trauma to which Griffiths was exposed.”

This is much the same critical debate as Picasso versus Matisse. “Did you do this?” asked the German officer on looking at “Guernica.” “No, you did” said the artist. The wartime history of Nice is not easy to find but it is hideous and there is not a trace of it in Matisse’s art.

The Tradition features a full-page illustration by Cyrlas Williams. “The Cat on the Wall”, a picture from 1922, is a light-filled scene created with buttery strokes of paint, its sunlight made of cream, yellow and pale blue. Need we require “intellectual critique” from an artist in his twenties? I think not. Form and colour that end in delight are sufficient. But then every eye is its own. The issue is not new, the same as John Berger versus Clive Bell. What matters is the climate for debate and opinion. A media response that is little more than an endless echo-chamber for advertising copy is a dampener of culture. So an end-of-year toast to the art critic who provokes. Vive la difference.