Steph Power reviews Wagner Dream by Jonathan Harvey and finds it to be a stunning portrayal of the ineffable, regarding death as a transitional stage.

Welsh National Opera, Wales Millennium Centre, 6 June 2013

Conductor: Nicholas Collon

Director: Pierre Audi

Designer and Lighting Designer: Jean Kalman

Computer Music Designers: Carl Faia / Gilbert Nouno

Sound Engineer: Franck Rossi

Cast includes:

Singers: Richard Wiegold / Claire Booth / Robin Tritschler / Rebecca De Pont Davies / David Stout / Richard Angas

Actors: Gerhard Brössner / Karin Giegerich / Chris Rogers / Ulrike Sophie Rindermann

Jonathan Harvey prefaced the score of his opera Wagner Dream with a dedication ‘by the composer to the benefit of all beings’. This simple statement encapsulates a world of meaning and compassion – and would have been intended by Harvey quite literally, in the sense of his enduring belief that the ‘purpose of music … is, in my view, to reveal the nature of suffering and to heal.’ Wagner Dream is ‘about’ many things but it is, most profoundly, a gift or ‘message’ from Harvey, in which he shares his beloved teachings of the Buddha through an imagined story about the death of Richard Wagner; a composer entirely opposite to himself aesthetically and temperamentally.

But the point is not the contrast between any two individuals – for it is Wagner’s own internal contradictions that concern Harvey; what he described as Wagner’s ‘immense egotism’ on the one hand and his compassion and aspiration to the divine on the other. The story of Wagner Dream turns on the perhaps surprising fact that Wagner himself nursed the idea of writing an opera on a Buddhist subject for many years (Die Sieger – The Victors), but died without realising the project. Harvey imagines that opera appearing to the dying Wagner in the form of the Buddhist parable he had hoped to make his subject, and Harvey uses it to show how Wagner’s suffering is caused by the obstinate resistance of ego, in the composer’s refusal to let go of the worldly attachments which keep him discontented and dissatisfied. It is only when Wagner relinquishes his ambition to manifest this final opera, and comes to understand that it is ‘already written’, that he can die peacefully after the heart attack that did, in fact, fell him on 13 February 1883 in Venice, where Wagner Dream is set.

In essence, Harvey’s opera consists of layers and layers of dream; it is Harvey dreaming about Wagner, and about what Wagner might have dreamt on his deathbed, and the underlying message is that life and death are themselves forms of dreaming, so to speak – or illusions, as a Buddhist might have it – experienced on the soul’s journey to enlightenment. Musically and dramatically, the piece is richly complex and subtly nuanced, and this production by Welsh National Opera – the first full staging of the work in the UK – is simply beautiful. Pierre Audi’s superb staging (a revival of the work’s world premiere in Luxembourg in 2007) contrasts and intertwines the realms of dream and nominal reality both literally and figuratively through the use of sets on different levels above and in front of the twenty-one musicians just visible centre-stage. Minimalist choreography and exquisite lighting by Jean Kalman contrasts the monochrome, unhappy darkness of Wagner’s domestic life with the vitality and sumptuously warm reds and golds of his imagined opera – the world of his potential spiritual awakening.

With speaking actors for the domestic scenes and singers for the opera-within-an-opera, the cast do a universally admirable job in holding our attention through the slow-paced but quietly compelling drama, during which many characters are on stage throughout. The parable itself concerns Pakiti and Ananda (exceptionally sung by Claire Booth and Robin Tritschler respectively, ably assisted by Rebecca De Pont Davies as Mother), whose unfolding story of transmuted, erotic love is observed by the dying Wagner (Gerhard Brössner) – to the consternation of his wife Cosima and mistress Carrie Pringle (Karin Giegerich and Ulrike Sophie Rindermann), who cannot see what he can see in that other realm. Straddling the worlds is the Buddha Vairochana (the splendidly deep-toned Richard Wiegold, beautifully complemented by David Stout as Buddha and Richard Angas as the dissenting Old Brahmin), who appears to Wagner as a teacher and to guide him through the process of dying; helping him to find the necessary calmness and resolution in submitting to the universe beyond ego, as Dr Keppler (Chris Rogers) calms him in the physical world without knowing what is happening to his spirit.

Harvey once said that ‘Messages can’t be avoided in music. Those who say that they are not interested in messages are really deluding themselves. Music is never value-free.’ Wagner’s final struggle is a portrayal of what, for Buddhists, is the crucial soul’s choice, and it is part of Harvey’s theological design that Wagner Dream should act as teacher and guide for us too, the audience, into the way of the Buddha. The original libretto (by Jean-Claude Carrière) was written in English (with Sanskrit mantras), but was widely seen as the opera’s weakest element; criticised for its unsubtle, didactic tone and lack of cultural authenticity. For this production, a translation was made into German and Pali with great success (the latter by Professor Richard Gombrich of the Oxford Centre for Buddhist Studies, with Russell Moreton, WNO Head of Music), utilising the 2000 year-old language which the Buddha himself would have spoken, and enabling the words in both the spoken and sung parts of the opera better to express Harvey’s cultural bridge-building – whilst, more importantly, helping the often pedagogic text not to interfere with Harvey’s mystical objective by ironically holding the opera earth-bound.

For it is the music wherein lies the real achievement of Wagner Dream and which carries most eloquently the heart of Harvey’s message. It is, in effect, a stunning portrayal of the ineffable – again, through many layers; here, expressed musically through his unique spectral-spiritual soundworld. Harvey tempers a post-Wagnerian, chromatic modernism with the underlying tonality seen increasingly in his later work, Eastern inflections and, above all, a love of translucent, ringing sonorities. His instrumental writing – performed here with exquisite feeling and attention to detail by the WNO ensemble under Nicholas Collon – is both delicate and vividly expressive, and the seamless entwining with electronic sounds lifts the music of this opera to the sublime. If I have one tiny criticism, it would be to suggest that the opening repeated ‘fog horn’ and attendant music could have been louder, better to set the watery Venetian scene and establish an important structural device. But, beyond that, the realisation was roundly magnificent and showed Harvey’s exceptional – and profoundly musical – talent for integrating acoustic with electronic music (thanks also to expert sound design by Carl Faia and Gilbert Nouno, who worked with Harvey at IRCAM and the live diffusion skills of engineer Franck Rossi). The audience were held simply rapt as the music swirled around the auditorium and generated the most moving climax as Pakiti was eventually accepted into the Buddhist order.

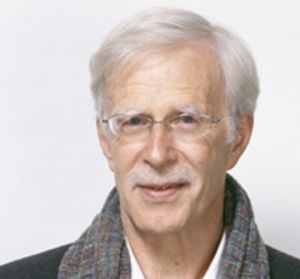

Death, for Harvey as for other Buddhists, is merely a transitional stage in an ongoing cycle of birth, death and rebirth – albeit a crucial one in terms of the opportunity it affords to shed unnecessary ‘baggage’. This production was, therefore, all the more poignant in its timing as a tribute to Harvey himself, who died last December after a long battle with motor neurone disease. To what extent the composing of Wagner Dream may have benefited him in his own preparation for death is impossible to answer. But the stages he shows of Wagner’s resistance bear an uncanny resemblance to the five stages of grief identified by the psychiatrist Elizabeth Kübler-Ross (with the author David Kessler), who described a process of, firstly, denial followed by anger, bargaining and depression before a coming to acceptance. The projection of Harvey’s picture onto the stage at the opera’s conclusion seemed not only to speak of the ultimate beauty of this process, but to offer a final blessing from this most modest and unassuming of men.

You might also like…

Laura Wainwright reviews the second novel by Samantha Harvey, All is Song.

Steph Power is a regular contributor to Wales Arts Review.