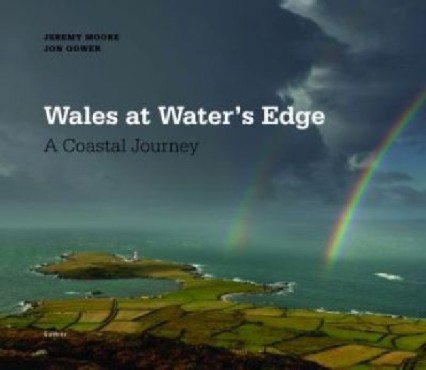

‘An endless succession of coves with blue skies that didn’t do justice to the subject.’ That was Jeremy Moore speaking in Aberystwyth’s Arts Centre on 17th May. He was referring to the coast of Wales as portrayed in certain photography books that have preceded Gomer’s celebration in word and image of the opening of the All-Wales Coastal Footpath.

Jeremy Moore includes a few coves; Bullslaughter Bay in a silvery first light, the rocks of Abereiddi shot from low down so as to resemble a half-submerged mountain range. But his collection of images takes in those parts of the coast’s industrialisation: Wylfa, the Transporter Bridge, the Dee Bridge encircled by pylons and barbed wire- ‘a certain angry beauty’ he says of the place. Puffin Island has been shot from the perspective of a hideous fish farm made of metal sheeting. With timely irony it is in Greek ownership and has since passed into receivership.

The photographs have been two years in the making and it shows. Starlings come nightly to rest on the struts of Aberystwyth’s pier. Moore has caught them in two rare opposing, enigmatic formations. For the dolphins of Cardigan Bay he has taken a boat out from Tresaith and waited until three are simultaneously leaping clear of the water.

by Jeremy Moore and Jon Gower

160pp, Gomer, £19.99

The designers at Gomer have made their book a marriage of text and image. There are twenty-two double page spreads but in the main the two share the page in complementary reference. On a left hand page a Ceredigion ecologist crouches in the low-tide mud at Borth. On the right hand page Jeremy Moore has caught a glossy ibis in full flight.

Travel writers excel in different ways. No writer on earth does water better than

Jonathan Raban. He captures it in words in the way that Petro does stone, Iyer disconnection and Theroux distemper. Jon Gower does estuaries. They are the places, from Goldcliff to Point of Ayr, where the twitcher meets the wordsmith.

Anthony Burgess once said, in an aside on Hemingway, that words alone are not enough. The writer needs to know about things. Down in the levels Jon Gower knows his reens and pills, stanks, gouts and coffee gouts. He knows whether a dragonfly has landed on frogbit, fool’s watercress or water crowfoot. He knows that knot bird goes to feed on the Baltic tellin, a pink-shelled bivalve. On the Gower brent geese breakfast on zostera. Ravens cronk, a sandwich tern skirricks.

Jeremy Moore has pictured Dylan Thomas’ boathouse like a sharp, pale Hammerhoi interior. Thomas here is ‘the boozy, cherub-faced bard’. His shadow can be seen in Gower’ s introduction. This coast is ‘crinkled, crimped, crenellated and corrugated- holidaymakered and lighthoused, dolphin-blessed, wind-sculpted and always wave-surrounded.’ True writing gets the distant view right but goes close up. Fisherman Martin Morgan is pictured beneath the Severn Crossing- a crossing, not a bridge. The fisherman has his waders but also a lanyard, a yew knocker and a snouter.

Gower captures colour in words as much as Moore in image. He sees pewter clouds, a marl-coloured lighthouse, water of bottle-green stains, a night of richest velvet. Bird’s-foot trefoil is carmine-yellow. The petals of kidney-vetch are tiny purple fireworks. Cefn Sidan has a long history of shipwreck; its fate in an age of modernity is to be turned orange by a wrecked consignment of suntan lotion.

Like many a good travel writer he seeds his journey with asides that sparkle. Scots has a word for sea mist that Welsh lacks. He locates Amazon’s vast warehouse. In Swansea, gentrification has turned a road from ‘express way to expresso way’. He pays tribute to Arthur Giardelli. In a marina the names of a couple of dozen boats go from Cadno and Azzurra to Wet Dream. Hostile American privateers apparently once seized post office ships between Holyhead and Dublin.

The eight hundred and seventy miles of the coast are an encyclopaedia of natural and human working. Gower’s journey has necessarily a hop and a skip to it. He gazes into Abereiddi’s lagoon but does not make the two miles to Porthgain, that wondrous place where the Sloop Inn presides over art galleries, fine fish eating and industrial ruins that evoke a lost city of the Mayas. He sees rightly a Solva that is more or less abandoned in winter.

Biography is part of the traveller’s alchemical art. An ingénue writer ladles it out like dollops of gravy. The wise use it sparingly as a flavoursome garnish. The author is owner of a much-loved Guide to British birds, a personal gift from British Rail. It is not common that a nationalised industry makes a gift to a Llanelli schoolboy. He recounts the reason why.

For a second printing Wales at Water’s Edge requires a few corrections. A comma has gone astray in chapter seven. The historian of capitalism, as well as its beneficiary is ‘Niall’ not ‘Neil’. He is revealed as owner of Sker House, the former grange of Neath Abbey. ‘Orang utan’ needs joining up. ‘Umbilical’ is an adjective rather than noun. The author meets ‘a dry stone-walling friend’. When Ingrid Bergman walked Snowdonia with a brace of Chinese orphans the film title contained the word ‘the’ twice, not once.

Publishers have responded to the digital world in differing ways. Some have cut costs, used cheap paper, bought glue that does not last, dispensed with proofreaders. Gomer is unusual in opting for total integration. Industry specialists will know whether the print operations outside Llandysul have done a better job than contractors in Asia might do. The authors, and the book’s audience, have been done superb justice. The binding beneath the jacket is coloured an aesthetic pale slate grey.

The colours of Snowdon photographed from Porthmadog’s Cob have the subtlety of a freshly restored Richard Wilson canvas. The early mists over the Teifi estuary are exactly it. A piece of Skomer with a small tanker at sea heading for Milford is rendered in tones of purple, pink, a range of greens. It is a reminder that enthralling beauty is right on our doorstep; it does need to be sought via an airport terminal and the unkind attentions of border custodians.

Travel books that are built to endure are few in number: ‘Eothen’, ‘the Great Railway Bazaar’, the best of the Welsh P’s, Perrin and Parker, Morris in Venice, Raban on the Mississippi, Magris on the Danube. Wales at Water’s Edge is the distillation of two creators’ lifetime experience. It takes its place besides these predecessors with honour.