Gary Raymond takes in the sights and sounds of the London Book Fair 2018, the first time in a long time Wales had a national stall present at one oft he world’s largest trade events.

It is here, in an aircraft hangar of deathless polish, that the industry of literature steps up shoulder to shoulder with those other efficient movers of global enterprise. There is a certain level you can hit with these things when all industries look the same, be it the manufacturing of AI, or weapons of war, or books. You hit a height and the homogenised corporate identity makes itself known. First thing you see on entering the London Olympia is the Harper Collins stall, docked front and (slightly off-) centre like a billion dollar yacht, its meeting plateau a veritable Gethsemane for publishing’s front guard, its LED billboards boasting the latest James Patterson-branded behemoth (Patterson doesn’t really write his books anymore, but rather employs a factory line of writers to turn his ideas into bestsellers). It is glitzy and serious and means business, and flip those LED screens to images of tennis-playing robots or soap powders and it wouldn’t necessarily make much difference. A few days walk, right at the back of the Olympia, a young woman sits glum and pallid in a four-foot cell masquerading as a stall, surrounded by never-depleting turrets of glossy science textbooks, her chair ignominiously pointed toward the girded roll-door of a loading bay and the stairs descending to the gents toilets. It’s not all about the bigboys at the London Book Fair.

Between these two contrasting images can be found hundreds of stands and stalls representing most of the countries of the world that have enough mullah to throw their hat in the ring. Each Fair has a trade focus, and this year is the Baltic states of Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia. It has taken years for them to prepare for this three day lollapalooza – Lithuania alone has funded the translation of eighty books into English. Latvia’s substantial stand is a hive of activity for the duration, more reminiscent of a fashion launch, just missing a Jacobim Mugatu figure at the helm, than an outreach for national literature. Are the tall attractive women dressed all in black about to spray perfume in my face as I walk past? No, they hand me a book catalogue.

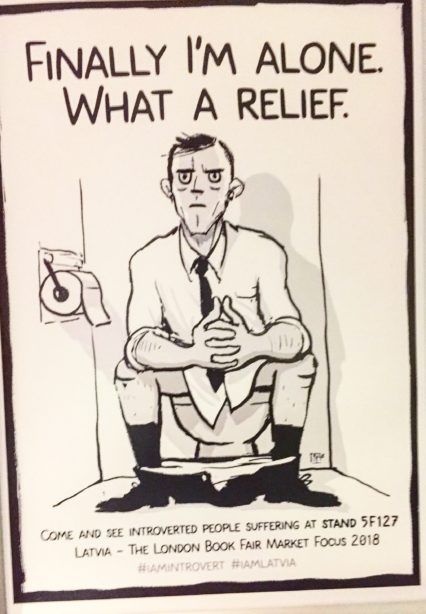

But Latvia seems fun. It seems several times I witness some man in a suit lifting himself from the floor as a bunch of people stand around in hysterical laughter, as if some prank just surpassed all expectations. (I never turn the corner in time to see what gets these men to the floor). Part of Latvia’s marketing budget has gone on a rather irreverent poster campaign (right) above every urinal in the building. (I am reliably informed a gender-altered version can be found in the ladies’).

But Latvia seems fun. It seems several times I witness some man in a suit lifting himself from the floor as a bunch of people stand around in hysterical laughter, as if some prank just surpassed all expectations. (I never turn the corner in time to see what gets these men to the floor). Part of Latvia’s marketing budget has gone on a rather irreverent poster campaign (right) above every urinal in the building. (I am reliably informed a gender-altered version can be found in the ladies’).

Everyone here is extremely smart, extremely focussed, and something about them suggests they are preparing themselves for the hitting of the wall, that moment when the physical demands of the Fair catches up, and blisters emerge like bubbles of lava, and finding a seat (I’d say at its peak the Fair caters on average one chair to sixty-three people) becomes less of a talking point and more a matter of survivalist zeal.

Next to Latvia’s black marble fashion launch, Italy has an airy spread – the tenders of this stall are stereotypically well presented – and a little further up is Poland, and Switzerland, and South America has its constituents scattered across the miles of floor. Wordsworth Editions is very proper, as it should be, in its burnt orange and high collars; Simon and Schuster has the gimmicky hit of the entire show, with a replica of the Oval Office and a Donald Trump impersonator – you can have your photo taken behind the presidential desk, like one of those Wild West period stalls at other fairs – America is all about the fun of the fair, it seems; China has a sturdy presence, a motel-sized stall that only displays supreme leader Xi Jinping’s The Governance of China Volume II; nice to see also Scientology creeping in with a stall dedicated solely to the works of religion-inventor L. Ron Hubbard, raising questions as to how the stalls proselytisers answer any questions that try to square up the fiction of the prolific sci-fi writer with the fiction of their religion. You barely walk five feet without some hitherto hidden world offering a fecund tangent.

And in the middle of all this (I mean, who knows where the actual centrepoint is of this place – it’s like walking around Leonardo di Caprio’s folding streetscape in Inception), is Wales. For the first time in a few decades Wales has a unified national presence at the London Book Fair, and it is immediately obvious it makes all the difference. This is not a single publisher, one little red face vying for attention in a poppy field of enthusiastic do-or-die red faces, but a representation of a national literature – not just books, but an idea, a culture. A slew of the Welsh publishers, along with facilitators such as the British Council, Literature Wales, Arts Council Wales, and the Welsh Books Council, have all come together to put their shoulders to the wheel to make this happen. And in the three days the stall is a hive of activity. Publishers, writers, dignitaries come and go, some are scheduled visits, but most are not. The London Book Fair is a branding exercise, it is about marketing, it is three days of taking meetings and exchanging pamphlets and catalogues, and dealing out honed pitches like playing cards, but the value of having a national hub was clear – the focus was on Welsh literature as a brand.

The importance of the Fair, of being here, has been weighed up by the beancounters of most organisations present. It is not an inexpensive venture, and whereas Harper Collins may not have to worry too much about cost, the value of being here may be up for discussion. For the organisers of the Wales stall, it was certainly a risk. But it is impossible not to have experienced Wales at the London Book Fair and decide this is where our country must be, this is the mix, this is a seat at the table, this is the party that stops people asking, “sorry, where?”

If Wales was ever guilty of an insular, suspicious attitude in its marketing of “the arts” then it’s an attitude that over the last few years has been resolutely cast aside. Outreach projects, international showcases, branding exercises – these terms might send shivers down the spine of some people with certain ideas of what an artist should be, but they are, at the very least, pro-active modern attempts to remedy immediate and potentially devastating modern problems. Although individuals made this work, each with their own reasons for doing so as well as a collective one, there were no poster boys or Court favourites, no elites, no conspiracies or hidden agendas, this was Welsh literature of the past, present and future, being presented as a phenomenon on one of the most influential platforms in the world. And rather than being condescended to, or dismissed, or rubbished, as some in Wales fear is the destiny of any Welsh person who sets foot over the Severn Bridge, Wales was embraced and discussed on a level with every other nation present.

A few days later, in a hotel in Aberystwyth, the Welsh Academy (the national society for writers in Wales) hosted an emergency general meeting to decide its future. In the year I have been a Director of this esteemed organisation, I have been surprised to find it now sits notably as a collective of individuals rather than as a unifying body, the most vocal of whom, it could be argued, use it to air their grievances (much of it personal and some of it simply egomaniacal) about the state of literature in Wales and its publishing industry. The future of the Academy after Saturday’s meeting seems somewhat brighter than it did on Friday, but the future health of Welsh literature will largely rest not with writers unions and forums (important as they are), but with collegiate efforts to brand our writing as something attractive in a modern fast-paced professional industry. Wales’ Minister for Culture Dafydd Elis-Thomas gave a speech to a packed stall on the Thursday, and enthusiastically endorsed the venture after a morning of meetings and tours, and pledged that not only must Wales maintain such a presence at the London Book Fair in future, but that it must look to heighten and push its ambitions in these arenas. (Frankfurt, maybe?). For now, in uncertain times, one thing is certain: anything less than the London Book Fair is a step backwards.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.