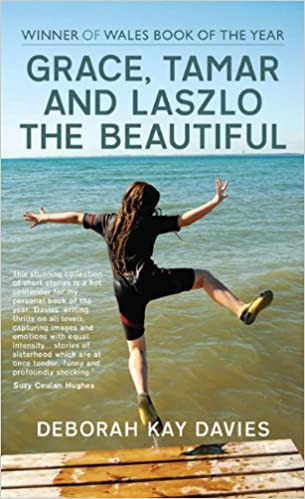

Continuing our celebration of previous winners of Wales Book of the Year, today we look at the foreword from Dr Becky Munford written for Deborah Kay Davies’ novel Grace, Tamar and Laszlo the Beautiful which won WBOTY in 2009. The new foreword was originally published by Wales Arts Review in 2021.

There’s less than a week to vote for Wales Book of the Year People’s Choice 2022. Wales Arts Review is proud to once again be sponsoring the people’s choice award, and to celebrate we’ll be looking back at a range of archive interviews, articles and reviews with previous WBOTY winners. Don’t forget to vote for the 2022 WBOTY People’s Choice winner, here!

*

Nothing prepares you for reading Grace, Tamar and Laszlo the Beautiful – the unflinching look at the savagery and strangeness of girlhood, the insistent violence inflicted on the female body, the deathly pulse of sisterly rivalry. First published in 2008, Deborah Kay Davies’ collection of nineteen interconnected short stories won the Wales Book of the Year in 2009. Set in the Gwent valleys, in a landscape that is at once recognisable and otherworldly, these stories tell the messy, sometimes terrifying, coming of age of two sisters, Grace and Tamar. Although the stories appear in chronological sequence, they are separated by the passage of time and shifts in narrative voice. The narration moves from first to third person, and from the brooding, furtive perspective of the mother to the by turns immediate and taciturn viewpoints of the two sisters. These narrative movements capture the sense of fragmentation and disconnection shaping individual identities and familial relationships across the collection. But it is also from the gaps and spaces in and between narrative perspectives that glimmers of understanding, of sisterly love and sympathy, shine through.

by Deborah Kay Davies

Available now from Parthian Books

The emphasis on perspective, on seeing things aslant (or not seeing them at all), is thematic as well as formal. This is a book that peeks and piques. The stories offer an oblique look at family, friendship, marriage, sex, desire; together, they create a multifocal view of the jealousy and disappointment, as well as the pleasure and discovery, that inflects the experience of growing up ‘girl’. Perhaps most unsettling about Grace, Tamar and Laszlo the Beautiful is its undaunted gaze at the violence enacted on and between the two sisters, whose discordant relationship troubles any romanticised image of sisterhood. In ‘The Point’, Tamar pokes out the blue eyes of her sister’s doll, Valerie, with the sharp end of a compass. The proleptic image of the blinded doll, whose eyes are turned full circle ‘so the pink backs were at the front’ and then re-drawn with a brown felt-pen, only barely forewarns of the story’s startling conclusion. Having pushed Tamar out of a tree, Grace finds her face down amongst the brambles. She turns her over to reveal a ‘sharp beech twig impaled in her blue, blue eye’. The unhurt eye is still moving.

Images of looking, of peeping and prying, run through the stories and are associated foremost with the mother, who feels that she has spent years of her life ‘[s]pying, glancing, checking through nets and blinds and half open doors’ in order ‘to understand something she’s actually reluctant to know’ about her youngest daughter, Tamar. Indeed, Tamar is unfathomable to both her mother and her sister, Grace. In her mother’s eyes, she is strangely unformed, ‘almost human, but not quite there yet’. Vital and unpredictable, she is in a state of becoming. The vulnerability of her body is powerfully conveyed through the insistent attention paid to her skin, the fragile frontier between inside and outside that is bruised, grazed and cut as the stories unfold. ‘Cradling Breezeblocks’, for example, depicts Tamar’s mother looking on as a rough block slides down her daughter’s shins, ‘peeling off a layer of tender skin’ each time she drops it; and, in ‘Whinberries’, she watches Tamar run her hands ‘through a clump of asparagus ferns’ until they bleed. In a particularly chilling poetic turn, the cardigan retrieved when Tamar goes missing is described as ‘a discarded skin’.

In contrast to Tamar’s exposed, sometimes knickerless, unruly body, Grace is clean and tidy. The orderliness of her body is communicated through her clothing, which plays an essential role in establishing her sense of self – and the social presentation of her girlish and womanly identities. While Tamar is associated with the harsh surfaces of the natural world – with stones, branches, mud and dust – Grace is immersed in the culture of femininity.

She is fascinated by the textures of her clothing, by the ‘feel of her new chocolate brown dress […] with its six layers of stiff, dark petticoat underneath’ in ‘The Point’ (in which she also experiences a ‘secret gladness’ to see that her sister’s dress is dirty with garden dust) and the ‘handfuls of cold chiffon’ in ‘Negligee’. But, the protection offered by these costumes is only ever precarious; these social skins cannot remain unblemished. The dark orange pollen smears left on Grace’s blouse in ‘Grace and the Basset Hound’ are scant preparation for the story’s harrowing denouement.

If this is a book about the chaos of sisterhood it is also one about the disorderliness of motherhood. The collection starts in a maternity ward with the traumatic birth of Tamar. Narrated from the mother’s distressed postpartum perspective, it opens with an image of a distracted male doctor throwing disinfectant into the ‘raw wounds’ of her ‘ruined’ body. This is the first of a number of shadowy and menacing male presences in the text; the smell of antiseptic lingers in the collection, reappearing with the image of Tamar’s heavily wounded body in ‘Stones’. The representation of the mother’s body as at once ethereal (‘[s]he has calming out-of-body times when she rises up and hovers near the fluorescent light strips’) and emphatically physical (‘the gaping hole between her legs feels as if it is spanned permanently with barbed wire’) captures the tension between interiority and corporeality that pervades the stories. But here the archetypal figure of the heroic and sacrificial Welsh ‘mam’ is deflated: Grace reflects in ‘The Point’ that her mother ‘looked like someone who had had the air extracted from inside’; in a later story, ‘Peckish’, she is disgusted by her mother’s gluttony, the sound of her masticating and the idea of her ‘mouth puckering up, pale and secret like a baby’s anus’. As the interrupted telephone call that structures this story suggests, the mother is unable to communicate with her daughters; for all of her spying and watching, she is displaced, inert, unknowing.

The disquiet that seeps through the collection is disturbed by a dark, but tender, humour. Moments of joy, of pleasure and laughter, ripple through the stories: the frissons of first love in ‘Kissing Nina’; the warm twinges of awakening sexuality in ‘Laszlo the Beautiful’; the contented self-exploration that opens ‘Grace, Ivanhoe and the River’. Although the sisters’ intuitive knowledge of one another has deathly turns (in ‘The Point’ and ‘Thong’), it is also playful (‘Fun and Games’) and powerfully compassionate (in ‘Stones’ and ‘Cords’, the closing story). Grace, Tamar and Laszlo the Beautiful is about a love that endures. The intimate connection between the sisters is conveyed with a poeticism that is as moving as it is savage. In the end, it is the fragile, but unbreakable, ‘cord’ running between Grace and Tamar, who are ‘at odds with each other’ and ‘strangely at one’, that holds the stories together in a beautiful, messy completeness.

Grace, Tamar and Laszlo the Beautiful by Deborah Kay Davies is available now from Parthian.

Becky Munford is Reader in English Literature with teaching and research interests in gender and feminist theory, modern and contemporary women’s writing, literary and visual cultures of fashion, dress and the body (especially trouser-wearing women), literary and cultural constructions of girlhood, and Gothic and spectrality.

This piece was originally published by Wales Arts Review in 2021.