Over the next week, Wales Arts Review will republish pieces from our archive that we hope will contribute to the conversations going on in relation to #BlackLivesMatter. We hope to offer a Welsh context to some of the issues, and to encourage further conversations, reflections and, hopefully, change.

This piece was originally published in September 2018.

*

Darren Chetty delves into the layered history behind the sign that once hung outside the local pub in Swansea when he was a child. In this piece, he brings together a web of personal and social stories on his journey to uncover the meaning behind this and many other ‘Black Boy Inns’ found over the country.

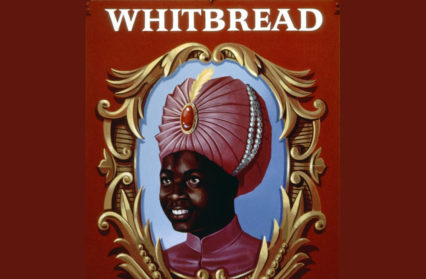

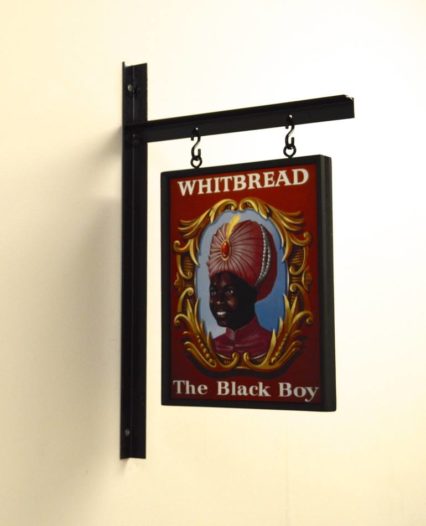

The rectangular, painted sign has Whitbread, the brewer, written at the top in white capital letters. At the bottom the text reads ‘The Black Boy’. In the centre, an oval with ornate livery is painted so that the brown background around it may be a wooden frame. There in the centre a boy is depicted in front of a royal blue background. He looks slightly to the right and appears to be smiling. We can see bright white front teeth. His skin is dark brown – almost black. On his head he wears a large, pink turban, the kind I might expect to see on a nineteenth-century maharajah or prince. Two rows of white pearls run from just over his left ear toward the back, or possibly the other side of the turban. The front of the turban catches my attention. Over twenty pleats in the shiny pink fabric meet at the centre and are covered, or perhaps held in place, by an oval jewel set in gold. Emerging from the top of the jewel is a single yellow feather that reaches a little higher than the top of the turban. He wears a matching pink shirt made of the same material as the headgear. No buttons are visible. It has a rounded collar that stands up – what is often called a ‘Nehru collar’ in Britain, and a ‘Mandarin collar’ in India.

I’ve seen photos of Indian men dressed in nearly identical outfits as the boy depicted here. But this is a sign that hung outside the ‘Black Boy’ pub in Killay, Swansea in the 1970s. The ‘ugly, lovely town’ of Dylan Thomas’s childhood was a city by the time I was born there, and Killay, once a mining village, was now a suburb of the city. I lived there from the age of four to age nine – from 1977 to the summer of 1982. But the sign I have described in such detail no longer hangs outside the Black Boy pub there. It was replaced by a different sign, which was soon replaced by another sign. Both these later signs depicted boys, but neither was black.

What happened to the sign I’ve just described?

But, that is only one of the questions I have. How did that sign come to be there? Who was the boy depicted? Why was he dressed so extravagantly and yet described merely as a ‘boy’? Was he black in the sense of being African, as the name and his face suggested? Or Indian, as his clothes suggested? What was his connection to the area?

These questions are not at all dissimilar to the questions I remember thinking about (though never saying aloud) as a child. I remember my Dad parking our blue Mini in the car park at the front of the pub so he could pop into the newsagents nearby. I looked up at the boy and wondered. When was he alive? And what language did he speak? Memory is a tricky thing, and forty years have passed, but I have a strong sense of wondering if he and I might have been friends.

So why my fascination with the boy in the sign? I wonder if it is because he was one of three dark-skinned boys I’d ever seen in Killay. The other two were my brother, some five years older than me, and a classmate of his, the son of a Goan doctor whose full name I recall even now, though I don’t think I ever had a conversation with him. He was Indian. My brother and I were Indian-South African-Dutch. We all had Swansea accents – though this would only become apparent to me when my family moved to England and everyday things I said were repeated by my new classmates with exaggerated imitations of what I still feel to be the loveliest accent in the world. Though I was the only person in the known history of my family to be born in Wales, I grew up with a definite sense of being Welsh, bolstered by my love of sport, and early aspirations to be a footballer and play for Swansea City and Wales. Having parents who had grown up in two different countries, and who put a great emphasis on fitting in, contributed to my sense of being Welsh – and a Swansea Jack – as something of a placeholder for an identity.

The Black Boy of Killay – by which I mean the boy depicted on the sign – was the only black person I saw in Swansea, apart from players for opposing teams that visited the Vetch Field, home of Swansea City. In September 1979, my father took me to my first football match. Over the next few years, I would see players such as John Chiedozie, Vince Hilaire, Bob Hazell, Alex Williams, Brian Stein and Ricky Hill, Cyrille Regis and George Berry.

Even after we moved away from Swansea, I continued to return to see ‘The Swans’ when time and money allowed. Returning intermittently to a place that holds so many significant childhood memories is a bit like time travel. On each visit, I note the changes to the city, how it is not the same place I once knew. But nonetheless there remain places that look and feel just as they did when I lived there, and in these places I am transported back, fleetingly and intensely.

Apart from the Black Boy of Killay, I rarely saw anyone wearing a turban in Swansea. The first time I did would probably be when my Dad took me to St Helens to watch Glamorgan play India. Another occasion was when we walked through Swansea indoor market on Saturdays and a market trader wearing a turban greeted my Dad with the words ‘Hello brother’. This was Narinder Singh, better known as Peter Singh, who was on his way to becoming a minor celebrity in Swansea as ‘the singing Sikh’, he branded himself as ‘the world’s only Sikh Elvis impersonator’. My Dad and Peter met when they both performed at a party for employees of Mettoy, where my father worked. Peter Singh’s songs include ‘Who’s Sari Now?’ and ‘Turbans over Memphis’. Backed by a band led by Martin Ace of the legendary Welsh group, Man. Singh can be seen in a 1986 documentary for HTV Wales singing ‘Rockin with the Sikh’:

‘I don’t smoke dope, I don’t drink bourbon,

All I wanna to do is shake my Turban’

The interviewer asks Ace if his lyrics are positioning Singh as an exotic gimmick. He denies that this is the case. ‘Rocking with the Sikh’ appeared on the album The Warwick Sessions, just before a track about football hooliganism at Swansea City matches, entitled ‘Trouble on the North Bank’. It was compiled by Swansea legend Ray Roughler Jones and features Keith Allen and his brother Kevin, who later directed the film Twin Town. It’s possibly the most Swansea album ever released. Perhaps Singh’s most well-known song was ‘Bindi Bhaji Boogie (Popadom Rock)’. Circa 1983, he was photographed, in full Vegas-era Elvis splendour, with The Clash. In 2001 Joe Strummer released an album that included a song entitled ‘Bhindi Bhajee’. I wonder if he remembered Peter Singh when he came up with that song title.

I can vividly recall the first time I considered the question of whether or not I was black. I was seven years old. We lived on an avenue in Killay up the hill from the Black Boy pub, where kids played outside regularly. I was running from my house to the end of the street for a reason that has not been retained in my memory. There may not have been a good reason. At that age running was what I did unless someone was telling me I had to walk. As I passed our next-door-neighbour’s green Triumph parked in its usual spot on the road in front of his house, I ‘pushed off’ with my right hand so as to give me extra speed. It’s a technique I’ve seen employed by children to this day. I was further along the road when I realised that the car was pulling alongside me. Mr Thomas, who had presumably been in the parked car, leaned towards the open window on the passenger side:

‘Keep your filthy hands off my car you black bastard.’

As I recall, this was the first time I experienced racial abuse. I think technically, it was the second. I remember the first time not as an event, but as a story in which I feature. In 1972, my white Dutch mother was in Gorseinon Hospital having given birth to me the previous day. A nurse remarked, ‘He’s a proper little Sambo isn’t he?’ When my father came to visit us in the hospital the nurse was nowhere to be seen. This three-sentence story lives on in our family. I wonder if the nurse has ever told it to anyone. I wonder if she even remembers it.

Far less common these days, ‘Sambo’ proved versatile as a racial slur. Whilst it was often used against African diasporic people, the black boy of Helen Bannerman’s children’s book ‘Little Black Sambo’ was Indian. The book was praised on its release and it was noted that Sambo outwitted the animals that threaten his well-being. Bannerman lived in Madras (now Chennai) for 30 years and would have been resident in Tamil Nadu at the same time as my great-grandfather, who later relocated to South Africa. Despite her familiarity with India, Bannerman chose to name her protagonist’s parents Mumbo and Jumbo. The book is now out of copyright but remains available on Amazon, where you can read reviews from people fondly recalling encountering it in their childhood. Two other books credited to Bannerman are also popular – ‘The Boy and the Tigers’ and ‘The Story of Little Babaji’. Both are rewrites of ‘Little Black Sambo’, published long after her death, with the most obviously racist content removed.

Things fade from memory. Or they don’t. The sign I  described at the beginning of this piece no longer hangs outside the pub. It now exists only in my memory. No – that’s not strictly true. A Google search leads me to a newspaper article and a web page for Daniel Trivedy, an artist based in South Wales. I discover I am not the only person who has noticed the changing signs outside the Black Boy in Killay. In the article, Daniel is quoted as saying: ‘Occasionally people find it necessary to alter the accounts of history to provide a more palatable version of events. Perhaps this is the case with the Black Boy pub sign. However, to ignore the black presence in our history (and pub signs) is to deny the roots and heritage of multicultural Britain.’

described at the beginning of this piece no longer hangs outside the pub. It now exists only in my memory. No – that’s not strictly true. A Google search leads me to a newspaper article and a web page for Daniel Trivedy, an artist based in South Wales. I discover I am not the only person who has noticed the changing signs outside the Black Boy in Killay. In the article, Daniel is quoted as saying: ‘Occasionally people find it necessary to alter the accounts of history to provide a more palatable version of events. Perhaps this is the case with the Black Boy pub sign. However, to ignore the black presence in our history (and pub signs) is to deny the roots and heritage of multicultural Britain.’

For his final degree show, Daniel exhibited a work entitled ‘Sign of the Times’, featuring a precise replica pub sign, with the turbaned Black Boy 1970s sign on one side and the image that currently hangs outside the pub on the other side. It is due to Daniel’s hard work in tracking down an image of the 70s sign on the Internet that I am able to offer the description of the sign in such detail at the beginning of this piece.

Another artist, Ingrid Pollard, published a book based on 20 years of research of Black Boy pubs in Britain. In ‘Hidden in a Public Place’, Pollard writes, “It is my contention that pub signs can be used to tease out hidden histories and heritage stories.” Pollard states that she is not primarily interested with pinning down a definitive explanation for this existence of Black Boy pubs, ‘because what I now believe is that the meanings of the linguistic and visual signs, have many points of origin and no one fixed meaning.’

Reading a published interview found on her website, I learn that Pollard’s interest with Black Boy pubs and the images that accompany them began on a visit to the Gower Peninsula, when she came across the pub in Killay. The same pub, and though the photograph in her book shows that ‘Beefeater Steak House’ has been painted over ‘Whitbread’ on the sign, the same image. Briefly I feel a strange sense of comfort, thinking that an acclaimed artist was trying to make sense of the sign at roughly the same time that I was gazing up at it from the backseat of my parent’s Mini. Then, in the same interview, she continues,

“I photographed the sign and they had a board outside with all these cocktails you could buy but they all had kind of really racist names like Jungle Bunny Orange and this and that pineapple drink so that was a bit weird, so I just kind of noted that… And they also had this bar that was outside in the shed and it was called ‘Black Boys in the Barn’, they were ‘going to town’ with the name and the connotations.”

Any sense of comfort vanishes.

A friend helps me to locate a recording of a BBC Radio 4 documentary presented by the poet Lemn Sissay, called ‘The Mystery of the Black Boy’. Lemn says these pubs are disappearing and could soon be a thing of the past.

He goes to ‘Black Boy’ pubs in Hertfordshire and Bristol and two in Bewdley, near Birmingham. In Bewdley, explanations offered for the name the ‘Black Boy’ are as follows:

Named after a local enslaved African

Named after King Charles II

Named ironically after the workers at a local windmill came in covered in white flour

Named after workers at a local windmill came in covered with soot on their faces

Lemn discovers that a local historian created theory number three without any evidence beyond there being a windmill near the pub in Bushey Heath. Lemn files theories three and four under ‘myth’ and comments that, ‘It’s interesting how speculation can become a kind of truth.’

A popular theory is that King Charles II had ‘swarthy features’ due to Spanish and Italian ancestry and Royalists would drink ‘to the black boy’. There is some historical evidence that Charles was considered dark-skinned, including a letter penned by his mother, Henrietta Maria, shortly after his birth in which she states, ‘he is so dark that I am ashamed of him.’

‘There are many things we’ve done in our history, that we’d best like to forget, shall we say, but it’s part of our history and it’s warts and all and to me it should always be commemorated because it is part of our history,’ said Alan Rose of The Inn Sign Society, in a 2008 Radio 4 programme called The Mystery of the Black Boy. Rose mentions the Black Boy in Killay and the change of sign from the one of my childhood to one of a young miner with coal on his face. He says that a lot of ‘Black Boy’ pub signs have changed because of the ‘PC politically correct brigade . . . instead of showing a small Negro boy they are changed to a Victorian chimney sweep.’ Rose doesn’t explain how this fits with his preferred theory that the name refers to Charles II, however.

‘Yes, it is important to preserve our past but should it be warts and all, however offensive, or is this selective amnesia, choosing what we want to remember and forgetting what we want to forget?’ asks Sissay. He informs us – or should that be reminds us? – that Charles II was himself connected to the enslavement of African people. In 1682 Charles II paid the Marquis of Antrim fifty pounds for a black boy slave. He, Charles II, encouraged the expansion of the Slave Trade and made a fortune directly from slavery – he granted a charter to the Royal African Company and was a shareholder.

Sissay concludes the programme by saying, ‘Personally, I wouldn’t walk into a pub called the Black Boy again. I’m a black man and I find the title a little derogatory and belittling. A throwback to less enlightened times when the black male was emasculated by being called a “boy”.’

John Evans, the owner of the Black Boy Inn in Caernarfon, North Wales, clearly disagrees. The inn, which was named ‘the Welshest pub in the world’ in 2016, has been the subject of some controversy over its name. But in 2008, Evans told the North Wales Daily Post, ‘I would never consider changing it, even if it was bad for business, because we have to hold on to our heritage.’ The images of black boys on the signs outside his pub look to me like racist caricatures. Perhaps these too are part of our heritage? I’m struck by how different they are to the boy depicted on the sign that hung outside the Black Boy in Killay. Is it just childhood nostalgia that allows me to see warmth and humanity in this portrait?

Gwilym Games, a librarian at Swansea Library, sends me two detailed emails in response to my request for help in uncovering the history of the Black Boy pub and the sign that hung outside in the 1970s.

‘Around the same time some taverns and coffee houses, places generally associated with tobacco use, also adopted the name Black Boy and an appropriate sign. These signs also might refer to the fashionable use of black or Asian servants and slaves by the wealthy, from the Tudor period onwards, and also because black workers might sometimes be found as waiters or bar staff. Black servants often wore coloured liveries and were regarded as an essential accessory for those of wealth and thus a painting of them could be turned into an impressive sign. It should be stated as well [that] coffee houses and taverns were also often used as trading points for the sale of slaves in places like Bristol and London until 1772 when Somerset’s Case freed all the domestic slaves in England and Wales. Other common pub names like the Blackamoor’s Head, the Turk’s Head and the Saracen’s Head testify to the way images of black people were commonly regarded as being perfect for use in pub and shop signs in earlier times, they were seen on booksellers and other shops as well.’

The stories that suggest the Black Boy as a pub name has absolutely nothing to do with African diasporic people offer little to help us understand the ‘Blackamoor’s Head’. Searching ‘Blackamoor’ I discover a vast number of exoticised depictions of African people, made in Europe. Some of them show men dressed similarly to the black boy in the sign. Blackamoors recently hit the news headlines after Princess Michael of Kent was photographed wearing one whilst on her way to meet Meghan Markle. After a photo of the Princess wearing the brooch was published in newspapers, a spokesman for the Princess said, ‘The brooch was a gift and has been worn many times before. Princess Michael is very sorry and distressed that it has caused offence.’

It does seem that many of the people who want to retain the name and signage of Black Boy pubs because they are part of British heritage are less interested in the historical events that led to their existence.

In his paper, ‘Identifying the Black Presence in Eighteenth-Century Wales’, the historian David Morris uncovered evidence that black people were bought, kept and sold as slaves in Wales as late as the 1790s.

‘In Wales during the eighteenth century it was the height of fashion to employ a black servant. In the popular mind-set Africa and the West Indies conjured up images of ivory, Guinea gold, sugar and coffee; in short, a limitless reservoir of wealth and luxury goods. A black domestic servant enables the owner to associate him- or herself with all that was fashionable about the New World. It also brought a touch of African exoticism into the parlours of rural Wales since there was no surer way to impress polite company than to have your coffee prepared, sweetened and served by a young black page,’ writes Morris.

This might do some way to explaining the name of the pub and the 1970s sign. The image is not unlike some of those painted by William Hogarth in the eighteenth century. David Olusoga’s ‘Black and British: A Forgotten History’ includes an image of an 18thcentury engraving that shows what he describes as ‘an enslaved black pageboy dressed in livery and turban’, which he comments ‘was an essential fashion accessory’ for courtesans of Georgian London. Perhaps the pub name and sign was not based on any particular local connections, but just part of a general trend in Britain?

But there is more.

Swansea’s growth as a town was largely due to its copper industry. Copper, mined in Cornwall, was brought by boat to Swansea where it was smelted. Estimates vary, but it is thought that in the early nineteenth century around half of the world’s output of smelted copper came from Swansea, earning the town the nickname ‘Copperopolis’.

This copper had many uses including ‘copper bottoming’ Nelson’s ships in the battle of Trafalgar, giving them improved manoeuvrability. The University of Glamorgan historian, Professor Chris Evans explains, ‘Copper and brass articles were important as trade goods on the Guinea coast of Africa, either in the form of copper rods, wire or ingots, or as ready-made semi-decorative items, such as manillas (bracelets), that eventually acted as an African currency . . . You could buy human beings with copper.’ One such copper manilla can be viewed at Swansea Museum.

Evans says this in an interview about his nomination of the White Rock Copper Works in Swansea for the book 100 Places that Made Britain. He notes that the first-known print of the works identifies one of the buildings as ‘Manilla House’. Black boys were bought with smelted copper from White Rock.

‘White Rock’ was the temporary name of the sports stadium built on the site of the old copper works in Swansea. It is the stadium that has been home to Swansea City since they relocated from the Vetch Field. It is now named, after its local sponsors, The Liberty Stadium.

The link between Swansea and slavery does not stop at currency, however. Professor Evans has unearthed evidence that Welsh industrialists put hundreds of slaves to work in horrific conditions in the copper mines of El Cobre, Cuba, decades after the Abolition of the Slave Trade in Britain. Despite the British Empire’s pride in its image as a foe of slavery, mine operators had managed to find loopholes in the law and hire slaves on long leases that Professor Evans describes as ‘pretty much tantamount to purchase’. The Company of Proprietors of the Royal Copper Mines of Cobre, in Cuba, had a head office in London, and had one Charles Pascoe Grenfell (1790–1867), as director of the company. Grenfell was a partner in Pascoe Grenfell & Sons, Swansea’s most powerful copper combine. Professor Evans writes: ‘[For] a generation the pull of Swansea’s copper smelters had drawn Cuba into a close commercial relationship with Wales. It was a relationship with deadly consequences for thousands of people of African birth or descent.’

This doesn’t provide an explanation for the naming of the pub in Killay. However, it does provide us with long-forgotten evidence of the links between Swansea and black people. It does seem that the memorable attire of the Black Boy in the sign from my childhood does indicate wealth – but that the wealth is not his own. As I read about it, I am reminded of the words my friend, the hip-hop artist Ty, when I showed him the Black Boy sign of the 1970s. ‘I am intrigued. But I know that the intrigue will end in disappointment.’

2017. Wembley Stadium. Swansea City are battling their way to a goalless draw against Tottenham Hotspur. A packed away-end is singing Max Boyce’s ‘Hymns and Arias’. I love this chorus and often find myself singing it hours after a match. We used to sing a carefully rewritten version every February at Hendrefoilan Primary School in preparation for our St David’s Day Eisteddfod. Our version had no mention of gambling, Soho sex workers and urinating in a beer bottle. Ours was a version stripped of all unsavoury content and humour. But the melody and the chorus remained. When I lived in Killay, my friend Martyn across the road would sometimes play his father’s copy of ‘Live in Treorchy’ as we played Subbuteo on his dining table. It’s the album that made Boyce synonymous with Welshness in the British imagination. Listening to the record felt a bit like being there in the audience at the gig. Boyce has since said that though intended affectionately, his song ‘Asso Asso Yogoshi, Me Welsh speaking Japanese’ couldn’t be recorded in this day and age. He may be right.

More mysteriously, I can’t find any discussion of a verse in ‘Hymns and Arias’ that has disappeared from the song as it appears on ‘The Very Best of Max Boyce’, released in 2005. This is despite the song being subtitled ‘Live in Treorchy’ and sounding as if it is the same live recording – the same, but not identical, evidently. The missing verse includes a line quoting a station guard at Paddington, who judging by the accent Boyce affects by the line is South Asian. It has disappeared without comment, without explanation. I wonder if people listening to Boyce’s compilation album remember the song well enough to notice that it has been edited. I can’t find a word about the removal of the verse on the Internet, our repository of collective memory.

‘Hymns and Arias’ reminds me that the Welsh National Anthem ‘Hen Wlad Fy Nhadau’, which can still make my hairs stand on end and bring tears to my eyes when sung before a major international, translates as ‘Land of My Fathers’. In his short book on the anthem, Zambian-born Siôn T. Jobbins notes, “It is a democratic anthem – it insults no one. It has no calls to conquer or humiliate others. It can be sung with gusto by people of all religions and none.”

Wales is not the land of my fathers. South Africa, India, The Netherlands could all be described in this way, I guess. I sing along, confident that my rather tuneless voice will be lost in the crowd. We move onto ‘Men of Harlech’ – I can at least clap in time – and then the Swansea City song;

‘Swansea Oh Swansea, Oh City, said I

I’ll stand there on the North Bank until the day I die’

Written by the late Roger Evans, it’s a song that made its first appearance on the Swansea terraces around the same year as I did, in an era of unprecedented success for the Swans under the management of the ex-Cardiff City and Liverpool player John Toshack. I attended my first game at the Vetch aged six. My father’s friend brought along two homemade folding steps – one for his son, one for me. A piece of wood attached to two others with metal hinges, these stools allowed us to stand at the front of the East terrace and peer over the wall, viewing the game at pitch level. This required a certain amount of care. At particularly exciting moments in a game when we shifted our balance too dramatically, the stools were prone to collapsing. We gripped the metal fence in front of us to help steady ourselves. By arriving well before kick off, we were able to take our position directly behind the goal, just a couple of yards from the goal line.

‘Take me to the Vetch Field, way down by the sea,

Where I will follow Swansea, Swansea City.’

We sing at Wembley, in full knowledge that the Vetch Field is long gone as a football ground. It lives on now as a place of significance to the football club and our younger selves, memorialised in song, and recalled weekly during the months of August to May. At the Vetch Field in that historic 1981–2 season, the Swans defeated Arsenal, Tottenham, Liverpool and Manchester United. Memories of these games are fortified, shaped and distorted by TV clips viewed first on VHS, now on YouTube. But when Wolverhampton Wanderers visited the Vetch Field, the TV cameras weren’t present. The match ended goalless, and was as dull as the score-line suggests. Yet one memory lingers. At one point in the match, when Wolves’ George Berry was close to the touchline in front of the North Bank, someone threw a banana towards him. Around me, on the East terrace, I heard laughter. Berry’s father was Jamaican. His mother was Welsh. He played regularly for the Welsh national team. But it was not his Welshness but his Blackness that was acknowledged by the banana thrower. And it was Blackness as less than human that was the ‘punchline’ of the ‘joke’. I learn in Alan LLwyd’s ‘Cymru Ddu/Black Wales’ that this act was repeated at the Vetch the following year, when, playing for Wales, Berry was racially abused by his own team’s fans.

These incidents came to mind in amongst the euphoria of Wales’s run in the 2016 European Championships. Reaching the semi-final and defeating tournament favourites Belgium, Wales were captained by a black man, Ashley Williams, and managed by Chris Coleman, born in Swansea a couple of years before I was, to a mother with Black-American heritage. The team included Swansea City’s Neil Taylor, the first player of Indian heritage to play in a European Championship. Against Belgium, another black player, Hal Robson-Kanu, scored the goal of the tournament (and in my view the Greatest Goal in the History of Football), wrong footing three defenders with one touch of the ball in the process. The multiracial composition of the squad didn’t warrant many newspaper column inches – commentators preferred to focus on the fact that the team outperformed England whilst including a number of players born in England, who wouldn’t have stood much chance of being selected for the country of their birth and the land of their fathers.

These incidents came to mind in amongst the euphoria of Wales’s run in the 2016 European Championships. Reaching the semi-final and defeating tournament favourites Belgium, Wales were captained by a black man, Ashley Williams, and managed by Chris Coleman, born in Swansea a couple of years before I was, to a mother with Black-American heritage. The team included Swansea City’s Neil Taylor, the first player of Indian heritage to play in a European Championship. Against Belgium, another black player, Hal Robson-Kanu, scored the goal of the tournament (and in my view the Greatest Goal in the History of Football), wrong footing three defenders with one touch of the ball in the process. The multiracial composition of the squad didn’t warrant many newspaper column inches – commentators preferred to focus on the fact that the team outperformed England whilst including a number of players born in England, who wouldn’t have stood much chance of being selected for the country of their birth and the land of their fathers.

At Wembley, the singing moves onto expressing disdain for Cardiff and then for England. I don’t join in. I’ve lived in England most of my life. I don’t hate the city of Cardiff, in fact I rather like it, and I don’t think the football team is worthy of so much of our musical attention. But Swansea City songs are often about defiant pride in a collective sense of marginalisation – Swansea is (alas, now ‘was’) the most westerly place in the Premier League; the second city of the third largest country in Britain. Perhaps this marginal identity, the outsider of outsiders helped me embrace Welshness as a childhood identity?

There is a lull in the singing. One young man in the row behind me chants, ‘I’d rather wear a turban than a rose’ followed by ‘No?’ as he fails to convince anyone to join in. I don’t look back but it crosses my mind that someone has pointed at Rageshri, my wife, and me and that this is why nobody sings with him. Or maybe they haven’t. I think of the Black Boy of Killay and his elegant pink turban. It crosses my mind to turn to the man and try to reason with him. Perhaps I could point out that the turban is an item of religious, or sometimes cultural clothing whilst the rose, like the daffodil or the leek, symbolises a national affiliation. So in fact one could quite easily wear both. But religion, culture and national identity, like football, don’t fall neatly into the rational realm. Did the Black Boy of Killay, finding himself in a land not of his fathers, consider himself to be at home? Did others come to recognise him as Welsh? If not, was this due to his turban or his skin colour? Could the people of Swansea even hold in their imagination a ‘Black Jack’ back then? Can they today?

Ten days later, I am speaking at the Bookseller Children’s Conference about the representation of Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic children. There is a noticeable emphasis on diversity at the conference and a desire to reach ‘new highs’. I suggest we should also reflect on ‘old lows’, and to illustrate my point, I tell people about some of the books I read as a child in Killay. I am part of a team of three, speaking about the YA book A Change is Gonna Come. Lauren Ace of Stripes Publishing speaks before me. It was Lauren who emailed me to invite me to write the foreword to the book. I immediately said yes and a few weeks later, Lauren approached me at the National Book Awards. I was there representing The Good Immigrant which had been nominated for an award. Much of the talk at The Good Immigrant table was at the alarming lack of racial diversity amongst the diners and I was feeling rather out of place at this black tie event. Lauren’s friendliness, together with her Swansea accent, made me feel a little less out of place. Lauren’s father is Martin Ace. At the Children’s Conference we share a stage, thirty-five years after her father shared a stage with Peter Singh.

Saturday 14 October 2017. I enter the Black Boy pub for the first time in my life, at the end of a busy day. Earlier that day I had visited Swansea library, to collect copies of cuttings featuring the Black Boy pub, before walking to a gallery on the High Street, which was holding an exhibition of memorabilia of ‘The Toshack Years’ at Swansea City. The exhibition was organised by long-time Swansea fan Pete Jones, brother of Rob Brydon, who is fund-raising for a documentary on The Swans under Toshack. I arrive ten minutes before the guest of honour arrives – John Toshack, the only British manager to have managed Real Madrid twice. ‘Tosh’ sits down and people queue politely to meet him and have photos taken. I tell my wife that when my family moved from Swansea to Devon, I was given the nickname ‘Tosh’ by a teacher and it was so widely used that some of the boys in the football team I played for didn’t seem to know my real name. For three years, I was identified by my peers and many of their parents as ‘Tosh’. I’m too nervous, or shy, or embarrassed, to queue to meet the original ‘Tosh’. I remember his youngest son briefly joined Fairwood Rangers, the football club I played for, and how excited we all would be that the Swansea City manager was watching us from the touchline, and how we would all try that little bit harder to be noticed by him. We eventually leave the exhibition and make our way to the Liberty Stadium to watch Swansea play Huddersfield Town. It is the only part of the day I spend fully focused on the present.

In the Black Boy pub, I am with Rageshri and my friend Paul and his partner Helen. Paul and I have been friends longer than we can remember, since before we could say the word ‘friends’. Our fathers became friends when my dad, newly arrived in Swansea from South Africa (via a five year stint in Ireland) joined the Taverners, a local cricket team.

Inside, the pub is warm, cosy and spacious. I pay close attention to the many pictures hanging on the wall. There are photos of the old Swansea docks and of streets in Swansea dating back to 1906. Above the table we sit at, there’s a photo of a pit pony underground, dated 1974. Behind me there’s an old poster advertising safety lanterns for mines, next to a display box with a Wales v England rugby programme from 1962, a match day ticket and a rugby boot. Photos of Phil Bennett and Gareth Edwards, names from my childhood, together with another display box for Glamorgan County Cricket Club – where I first saw Viv Richards, Clive Lloyd and Javed Miandad play – are in the far corner. Given the wealth of local history on display, I’m a little disappointed not see anything relating to Swansea City on the walls. But much more than this, I’m struck by the absence of anything relating to the history of the Black Boy pub itself, save an oil painting of the pub. The sign that hung outside when I was a local is now long gone. It was first replaced by a picture of a smiling white boy with coal on his cheeks – Black Boy as Minor Miner. This sign gave way to the present one. A boy in perhaps Victorian garb, including a black jacket and hat, slightly unkempt, whose is looking to his left, his eyes not visible to us. He is white. The sign of my childhood is nowhere to be seen.

We order food. I go for vegetable tikka masala, which comes with half and half (half rice, half chips), a fine Welsh tradition. I notice Welsh Beef Madras on the menu. Our waitress takes our order. She is a young white woman, perhaps a student. This is unremarkable but noticeable to me as she wears a green staff shirt that has in capital letters ‘BLACK BOY’ written over one pocket. It seems as though she has been misidentified. But every member of staff wears the same shirt. The same words are written on the mirror behind the bar. But where is he?

As I tuck in to my food, I sense his presence. Perhaps it is because I have printed off a copy of the old sign to show Paul. Perhaps it is because I can read the words on every member of staff but not see any image or any other form of acknowledgement of him. Perhaps it is because there are no black boys, girls, men or women in the pub. Or because when Helen, Paul’s partner, enquiries at the bar as to the pub’s name and history she is met with blank expressions. Nobody knows. The interior of the pub is bursting with memorabilia and local history. Yet, there is nothing at all that helps us to understand the history of the pub’s name, the sign that hung outside when I lived up the hill, or its replacement with images that appear to have increasingly less connection to the name. It seems as though nobody cares about the Black Boy of Killay. Perhaps he never in fact lived. Yet for me, at least, he lives on, in memory.

**

Special thanks Gwilym Games at Swansea Central Library, and to Miranda Kaufmann for making me aware of Ingrid Pollard’s ‘Hidden in a Public Place’. An earlier version of this essay was published by Boundless, funded and run by Unbound publishers.

**

Darren Chetty is a writer, teacher and researcher. He has published academic work on philosophy, education, racism, children’s literature and hip-hop culture. He is a contributor to the bestselling book, The Good Immigrant, edited by Nikesh Shukla and published by Unbound. Darren is co-author, with Jeffrey Boakye, of the forthcoming What Is Masculinity? Why Does It Matter? And Other Big Questions published by Wayland.